Dispute Resolution in the Era of Reconciliation: Recommendations for the Revitalized Environmental Assessment Process in British Columbia

Frances Ankenman, J.D. Candidate 2020, University of Victoria

1 INTRODUCTION

Catalyzed by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)[1], the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Calls to Action[2], recognition of Aboriginal rights and title under s.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, landmark court decisions, and growing pressure for governments to recognize and address past and ongoing harms to Indigenous peoples by colonial governments, Canada has entered an age of reconciliation. Governments across all levels in Canada are pursuing a broadening number of legislative and policy initiatives that share the central goal of renewing and improving the relationship between the Crown and Indigenous peoples.

In British Columbia (B.C.), the current provincial government has reflected their commitment to reconciliation through reform priorities identified in mandate letters to ministers[3], key policy documents such as the Draft Principles that Guide the Province of British Columbia’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples[4], and commitment to implementation of UNDRIP into provincial law[5]. In November 2018, the British Columbia (BC) government introduced and passed Bill 51, Environmental Assessment Act (“the Act”)[6]. The bill was advanced with the purpose of reforming BC’s environmental assessment (EA) process for resource projects[7] to “ensure the legal rights of First Nations are respected, and the public's expectation of a strong, transparent process is met”[8].

The revitalized Act is a key piece of legislation advanced by the provincial government in support of its broad commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Changes to the EA process that have been introduced in support of reconciliation include an earlier and more inclusive engagement process with nations, measures for Indigenous-led assessments, and a time-restricted, non-binding mediation-style dispute resolution (DR) process that is “consistent with Indigenous approaches to governance”[9].

Environmental assessments in B.C. inform major land and resource decisions in the province and, as such, often have ecological, social and/or economic implications for Indigenous nations. Disputes involving Indigenous nations can arise in several contexts within an environmental assessment process, including concerns regarding unmitigated or cumulative impacts to Aboriginal rights and title or other ecological/cultural resources, inadequate Crown consultation and accommodation, and lack of consent at key stages of an environmental assessment. Under the current environmental assessment process, disputes involving Indigenous nations are typically resolved through consultation and accommodations made by the Crown as represented by the Environmental Assessment Office (EAO). Indigenous nations involved in major disputes that are not settled through the EA process may seek resolution through the legal system.[10]

The DR mechanism is planned to assist where consensus with Indigenous nations is not reached at key stages of the new EA process, from the first identification of Indigenous nations to participate in an EA to the final decision of whether to issue an EA certificate.[11] The Act grants Indigenous nations participating in an EA and the chief executive assessment officer with the authority to refer matters to the DR process, which stops the clock on legislated EA timelines and prohibits the EAO from making decisions on the matter until completion of the DR process.[12]

The proposed DR mechanism presents opportunities to reduce and resolve issues more effectively within an EA process through formal resolution of conflicts early in the process.[13] If implemented carefully, the proposed DR mechanism could lead to several possible benefits, including fewer applications for judicial review of EA decisions, confidentiality of the DR process, negotiation of creative solutions, greater sense of ownership of process by parties to the dispute, and relationship-building among parties. Most importantly, a DR system would offer parties the opportunity of negotiating mutually-satisfactory outcomes, rather than having decisions imposed unilaterally by the Crown or by a judgement of the court.[14]

More broadly, a carefully implemented DR process can further the act’s goals of supporting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples by supporting the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), recognizing inherent jurisdiction of Indigenous nations, and acknowledging Indigenous peoples’ rights recognized and affirmed by s.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.[15] Despite these opportunities, there are deep, complex and interrelated challenges associated with the implementation of a DR system in an inter-societal context with complex historical relationships between Indigenous peoples, the Crown, and the resource development industry.[16]

The purpose of this paper is to identify major challenges and limitations presented by the proposed DR model and propose specific mitigative recommendations for its implementation. This research focus was developed in collaboration with the EAO to provide the Crown and Indigenous nations with research to guide the development of the policies and procedures needed to implement the DR mechanism under the revitalized Environmental Assessment Act before the legislative scheme comes into force in late 2019.

Research for this paper is drawn from both theoretical perspectives and case studies where DR models have been applied to resolve intersocietal[17] disputes. Given that intersocietal land and resource DR in Indigenous contexts is an emerging practice and research area, there are limited academic and practical experiences from which recommendations can be drawn. The challenges and recommendations identified in this paper are therefore not comprehensive and are likely to shift as the model becomes more closely defined through future engagement with Indigenous nations in the planning process.

2 CHALLENGES OF INTERSOCIETAL DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN INDIGENOUS CONTEXTS

The following sections examine broad challenges to the effective implementation of the model presented by both the model’s proposed structure and contextual factors. Key recommendations emerging from the challenges are identified within each section.

Challenge 1: Addressing Diverse Interests, Issues and Relationships

A central challenge in developing the DR model is accommodating the wide range of interests, worldviews, relationships and issues with which the process will interact. This challenge is set against the backdrop of the goal of developing the model in accordance with principles of Indigenous governance.

The DR model will likely most commonly assist in the resolution of disputes between or among Indigenous nations (eg. territorial dispute), between Indigenous nations and the EAO (eg. lack of consensus at a key decision point), and possibly between Indigenous nations and project proponents (eg. inadequate mitigation of Indigenous concerns in an application for an EA certificate)[18]. Disputes may also be multilateral, implicating unique combinations of these parties and possibly others (eg. other regulatory agencies).

Further complicating these situational challenges are Indigenous nations’ historical and ongoing intergovernmental relations with the provincial Crown. The Crown has a complicated relationship with many Indigenous nations arising from historical processes of colonization and dispossession of traditional territories. Contemporary disputes about land and resources are often perceived by Indigenous nations as acts of colonization and inevitably implicate these deep, complex issues.

Aside from contextual diversity, the disputes themselves brought before the DR system may vary widely in scope and complexity and relate to a wide range of issues such as treaty rights, Aboriginal rights and title claims, Crown consultation, Impact Benefit Agreement (IBA) negotiation, and implementation of UNDRIP in the EA process.[19]

The primary recommendation emerging from this report is to develop a DR process that is adaptable to the specific parties and Indigenous legal traditions with which it engages. This proposed approach would avoid the dangers of a “one size fits all” approach, which would likely fail to meet the diverse needs of those involved in the DR mechanism. This approach would instead acknowledge the wide variety of traditions to conflict resolution available within each Indigenous legal order.[20]

To accomplish this goal, this report recommends the development of a high-level regulatory and policy framework and delegation of procedural details to the pre-mediation stage of a dispute brought into the process. This approach would allow parties to play an active role in determining issues such as the structure, format and location of the mediation. Where parties are unable to come to a consensus about the procedural details of a mediation, a standard mediation process defined in policy may operate as a backstop.

To facilitate the delivery of the DR mechanism, this report recommends the appointment of a “Mediation Advisor”. In a model that will engage many mediators, each of whom may have different styles, backgrounds and perspectives, a Mediator Advisor role would ensure both consistency of process and alignment of individual DR processes with Indigenous principles of governance where requested and feasible. A Mediation Advisor could also manage the mediator roster, coordinate intercultural mediation training and recommend specific mediators to parties applying for mediation.

This model is adopted by the New South Wales Community Justice Centres in Australia.[21] In that setting, a Mediation Advisor typically conducts pre-mediation meetings and capacity building and transfers the dispute to a mediator to avoid perceptions of bias in favour of Indigenous parties.

Challenge 2: Addressing Underlying Interests within Limited Scope

To the extent that the range of issues and solutions that could be negotiated within the proposed system are anticipated to be restricted to issues relating to the EA process, the DR model will have a limited ability to respond to parties’ underlying needs.

Time-bound mediation is often most successful in facilitating resolution where issues in dispute are “discrete, well defined and not open-ended”[22]. While issues brought forward through the proposed mediation model may be tailored to have a narrow focus, land and resource disputes typically likely engage deep, complicated issues arising from historical and ongoing relationships between Indigenous peoples and the Crown.

Where DR processes ignore these historical factors and instead focus on the future as it relates to narrowly defined issues, the process may prioritize non-Indigenous interests.[23] “Quick-fix” agreements arising from a forward-focused DR process will likely leave many underlying issues unresolved and limit the effectiveness of the model to meet the needs of parties involved.[24] This concern may be compounded by time limits placed on a DR process, which must be set in consideration of the broader timeline of the EA process.

In addition to the implementation of a legislated maximum timespan for all DR processes, the proposed process should also require parties to a mediation to identify a non-binding anticipated timeline set within the maximum timespan. The agreed upon anticipated timeline should be defined in consideration of the anticipated scope of issues and the nature of the relationships among parties. Setting an anticipated timeline would help create common expectations for both parties and begin a process of consensus-building from the beginning of the DR process.

Owing to the novel nature of the proposed DR model, there are limited examples of similar processes in place that can provide insight into appropriate timelines. A regulatory framework closely related to the proposed model is the Australian Native Title Act[25], which enables a DR process for Indigenous nations and mining companies. The process is designed to be future-focused and limited in scope, and sets a maximum timespan of 6-months, after which either party may refer the matter to arbitration.

Where the identification of issues in the pre-mediation stage suggests the scope extends beyond the mandate of the EAO, efforts should be made to secure representation from other provincial ministries where appropriate and feasible within the broader timespan of the EA process. Bringing these parties to a dispute resolution can support goals of reconciliation by supporting dispute resolution more holistically.

Challenge 3: Developing Model in Accordance with Indigenous Principles of Governance

Indigenous nations in BC have unique and long-standing traditions of DR. While Indigenous legal traditions may share some broad similarities in the paradigms underlying their DR traditions, a “one size fits all” approach grossly oversimplifies the Indigenous legal landscape in BC and is unlikely to meet the goal of operating in accordance with Indigenous principles of governance.

This diversity in governance traditions presents a challenge for the effective implementation of the proposed DR model and supports the recommendation of designing a highly flexible process.

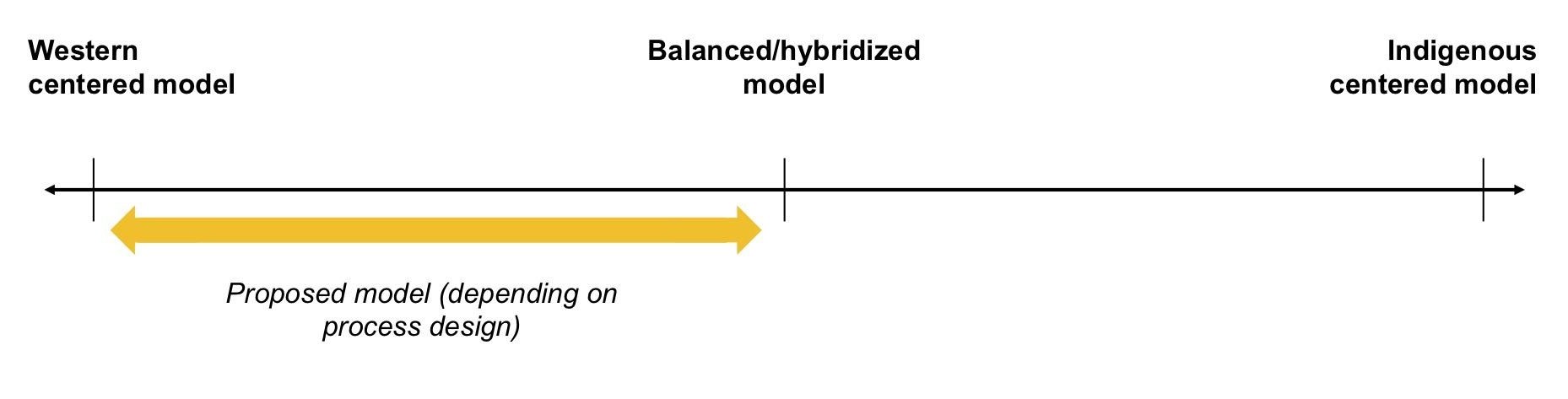

While there are opportunities for the proposed model to be developed in accordance with some principles of Indigenous governance, the legislative framework within which the DR model will operate limits the ability of the model to operate in full accordance with principles of Indigenous governance. The ability for Indigenous nations to provide or withhold consent for decisions affecting their territories is a fundamental tenet of Indigenous governance.[26] To the extent that the Crown will retain ultimate decision-making authority where DR fails, the proposed model will be limited as a process ultimately grounded in Western principles of DR (see fig. 1 below).

“Indigenization” of Western models of DR[27] has been critiqued by scholars as only providing incremental modifications to conventional processes that fail to address impacts of colonization.[28] This approach has been more deeply criticized by authors such as Bell, who posits that “if only those parts of indigenous knowledge, values and processes that do not conflict with Western values and law are adopted, the internalized oppression experienced by some Aboriginal peoples is reinforced and further cultural assimilation is promoted”[29].

Fig. 1 - Conceptual diagram of proposed DR within societal paradigms (adapted from Victor 2007)[30]

Fig. 1 - Conceptual diagram of proposed DR within societal paradigms (adapted from Victor 2007)[30]

While the proposed model is limited in its structural design to become at best a balanced hybridized model in accordance with both Western and Indigenous principles of governance, there are opportunities to decentralize Western principles by building in flexibility to align a DR process with principles of Indigenous governance.

Indigenous parties should have the opportunity to develop the structure of the mediation process in collaboration with a Mediation Advisor (see “Challenge 1” above) and integrate aspects of their nation’s legal tradition into the mediation process. Integration of Indigenous approaches may include principles (eg. relationship-centered DR approach) and practices (eg. traditional ceremonies). While Indigenous and non-Indigenous principles of DR may be difficult to reconcile and at times be fundamentally incompatible, there are some aspects that can more easily be integrated into a mediation process. In the Barramundi Gap in Australia, for example, involvement of non-Indigenous mining representatives in Indigenous ceremonies played a central role in bridging worldviews and resolving ongoing land disputes.[31]

Examples of ways a pre-mediation meeting can be used to support integration of Indigenous parties’ preferences for DR include discussion of the following key areas:

- Identification of Indigenous social and kinship rights and obligations that inform who from the community should be present in the mediation and what their roles should be.[32]

- Preference for direct or indirect communication in dispute settings: The English language has been described by some Indigenous speakers as “too direct”[33]. While Western approaches to DR often involve early identification and discussion of issue(s), many Indigenous traditions approach disputes by discussing “everything but” the issue, approaching resolution of the issue itself at the end of a DR process.[34] In this way, Indigenous systems often centre on relationships, while many non-Indigenous processes place emphasis “on the dispute itself and resolution outcomes”[35].

- Identification of any ceremonial and/or spiritual traditions to be included in the DR setting.

- Identification of relevant legal or guiding principles that the nation would like to be upheld in the DR process.

As a note of caution, the success of the proposed model does not necessarily depend on the degree of “indigenization” or degree of alignment with traditional Indigenous principles. Some representatives may be less traditionally-oriented and may be more comfortable operating in a Western adjudication system, as was found in the implementation of the Navajo Peacemaker DR system.[36] Representatives may similarly have concerns about applying traditional models to contexts outside their nation. The focus should therefore be placed on building a process to suit the needs of the representatives of Indigenous nations within the context of the dispute.

Challenge 4: Addressing Power Imbalances

There are unique challenges associated with power imbalances between parties that would be likely to engage with the proposed DR mechanism.

While there are undoubtedly power differentials between project proponents and Indigenous nations arising from the unique circumstances giving rise to a particular dispute, there are power imbalances between the Crown and Indigenous nations arising from their historical and ongoing relationships. Importantly, there is an inherent power imbalance in the proposed DR model arising from the Crown’s residual ability to issue a decision where parties do not reach agreement through the DR process.

Generally, mediators are trained in identifying and mitigating power imbalances within a mediation session. Beyond ensuring mediators are appropriately trained in this way, this report proposes a number of recommendations that support the goal of offsetting power imbalances. Recommendations for balancing power dynamics flow from a recognition that the mediation process design can significantly affect cultural neutrality and advantage the needs and interests of one group over another[37].

First, pre-mediation meetings between mediators and Indigenous nations participating in mediation can be a tool for building capacity within the Indigenous nation to negotiate effectively in the context of a mediation. This may be especially important in contexts where an Indigenous nation has limited experience in Western mediation settings. An example of a DR model with pre-mediation capacity building training for Indigenous parties is the Community Justice Centre (CJC) model in New South Wales, Australia.[38] To address concerns of bias toward Indigenous parties receiving capacity training, the CJC model typically engages different mediators in the pre-mediation and mediation stages. Pre-mediation meetings with non-Indigenous parties that seek to increase understanding of the non-culturally neutral aspects of a DR process may also support the goal of addressing power imbalances.

Second, Indigenous parties should be offered the option of communicating in the mediation in the language of their choice. For many Indigenous nations, there are close ties between language and culture, and allowing Indigenous parties to participate using their Indigenous language may allow them to communicate their perspectives, relationships and emotions without losing meaning through translation.[39] While translation will ultimately be required where there are non-speakers represented in the mediation, allowing a party to communicate first in their language allows a more uninterrupted flow of thought. More broadly, moving away from default operation in English offers respect to Indigenous parties and contributes to a more balanced mediation approach.

The ability of the proposed model to address power imbalances depends not only on its structural design, but also the willingness of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties to engage in a respectful intersocietal dialogue and attempt to understand other parties’ perspectives. To this end, this report supports the creation of a code of ethical conduct that provides clear standards that support a culturally respectful space, as has been applied in the Native title DR model in Australia.[40] Further, Indigenous nations should be consulted with and have the opportunity to communicate their consent for the individual representatives of the Crown, proponent, other Indigenous nations, and anyone else proposed to attend the mediation.[41] The Mediation Advisor should review proposed representatives to ensure that the number of representatives is relatively balanced. These recommendations would help ensure that the people participating in the mediation process will contribute to a respectful and balanced discussion.

Challenge 5: Selecting Appropriate Mediators

The selection of mediators is a critical consideration in designing a DR model in an intersocietal context as it connects to perceptions of bias, which may fundamentally impede parties’ perceptions of the mediation process.

First, there may be broad conceptual differences in the role of a mediator in Indigenous and non-Indigenous settings. The concept of mediator neutrality is central to Western mediation models. By contrast, in many Indigenous traditions, disputes are resolved by engaging those who are intimately aware of the issues, relationships, and applicable legal principles.[42]

Conceptual differences aside, there are challenges associated with appointment of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous mediators. Non-Indigenous mediators may be perceived as biased toward non-Indigenous parties and interests[43], or may actually be unintentionally biased because of factors such as training in exclusively Western mediation skills[44], lack of intersocietal conflict resolution training[45], or gaps in understanding of Indigenous values and worldviews.

There may similarly be difficulties associated with appointing Indigenous mediators. Where a mediator has close personal ties to those involved in a dispute, this may be seen as sources of bias toward particular Indigenous families or groups.[46] This challenge is particularly relevant in disputes among Indigenous nations. There may similarly be traditional gender and/or kinship roles that make a particular Indigenous mediator more or less appropriate for engaging in the dispute resolution process.

There are several recommendations that flow from the challenges associated with mediator appointment and training.

S. 5(1) of the proposed act allows the Minister to appoint mediators to disputes in consideration of any recommendations made by an Indigenous nation.[47] The Minister should consider adopting a policy of appointing mediators only where the participating Indigenous nation(s) has(ve) provided their consent. Mediation offers the significant advantage over adversarial processes of empowering parties to have a greater degree of control over the dispute. Appointing mediators without the consent of participating Indigenous nations, even where they have received adequate training, could frustrate the benefits of a mediation-style process and marginalize and disempower Indigenous nations.

Some authors have recommended the use of co-mediators in intercultural DR settings. Co-mediation is a process in which two or more mediators “play well-defined and mutually understood complimentary roles as well as providing checks, balances and support for each other, and effective debriefing and planning”[48]. In an intersocietal context, co-mediators could be used to ensure a balanced understanding of Indigenous and non-Indigenous approaches. This report recommends supporting co-mediation where one or more parties have concerns surrounding the mediator’s status as an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person. Co-mediation settings should similarly require consent from all parties for both mediators appointed.

Mediators who are agreed upon by parties in a particular dispute should be required to undergo training in cultural fluency, defined here as familiarity and facility with cultural dynamics as they shape ways of seeing and behaving[49], to develop a closer understanding of the participating Indigenous nation(s).[50] This requirement would help reduce real or perceived bias, and address issues of power imbalances between Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties.

CONCLUSION

If implemented critically and with a view to support integration with Indigenous principles of DR, the proposed model under the revitalized EA process can play a significant role in advancing the provincial government’s goals of reconciliation and respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Ensuring Indigenous parties are engaged and respected in the proposed DR process requires developing a model that is “sufficiently responsive to their cultural understandings and needs to attract [their] trust and allegiance”[51]. Implementation of the recommendations developed in this report and those further identified through consultation with Indigenous nations can help ensure the model responds to the needs of Indigenous parties, supports government commitments to reconciliation, and respects the diversity of worldviews and legal traditions in the province of B.C.

Endnotes

[6] Bill 51, Environmental Assessment Act (2018), will replace the Environmental Assessment Act, SBC 2002 when it comes into force in late 2019.

[8] The Honourable John Horgan. (2017). Premier’s mandate letter to Minister George Heyman.

[10] Recent court challenges brought by First Nations in BC challenging the EA process include Squamish Nation v. British Columbia (Environment), 2018 BCSC 844, West Moberly First Nations v. British Columbia, 2018 BCSC 1835, Coastal First Nations v. British Columbia, 2016 BCSC 34.

[11] Other key stages include: decision of whether to commence an EA, exempt the project from an EA, require a revised Detailed Project Description, or terminate the process; type of assessment and the Process Order. In addition to these stages, any other prescribed matter may be referred by participating Indigenous nations and the chief executive assessment officer to the DR process. See s.5(2)(c) of Bill 51, Environmental Assessment Act (2018).

[13] Goldberg, S. B., Sander, F. E., Rogers, N. H., & Cole, S. R. (2014). Dispute Resolution: Negotiation, mediation and other processes. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.

[16] Jones, C. (2002). Aboriginal boundaries.

[17] This paper employs the use of the term “intersocietal” in place of the more commonly used term “intercultural” to describe processes operating across Indigenous and non-Indigenous contexts. The use of the term “intersocietal” is applied to recognize that Indigenous societies encompass a broader range of dimensions than their cultural identities.

[18] It is uncertain, as of December 2018, whether the DR mechanism will apply to conflicts between Indigenous nations and proponents. For the purposes of this paper, it is assumed that the model will apply to these situations.

[19] Province of British Columbia. (2018). Environmental Assessment Revitalization: Intentions Paper.

[24] Bauman, T. (2006). Waiting for Mary: Process and practice issues in negotiating Native Title Indigenous decision-making and dispute management framework. Land, Rights, Laws Issues of Native Title, 6(6). p.4.

[26] Doyle, C. (2014). Indigenous peoples, title to territory, rights and resources: The Transformative role of free prior and informed consent. London: Routledge.

[28] Friedland, H. (2014). Accessing Justice and Reconciliation Project.

[29] Pirie, A. Commentary: Intercultural dispute resolution initiatives across Canada. In Bell, C., & Kahane, D. Eds. (2004). Intercultural Dispute Resolution in Aboriginal Contexts. Vancouver: UBC Press. p.331.

[30] Victor, W. (2007). Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in Aboriginal contexts.

[31] Federal Court of Australia (2009). Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution. p.97.

[32] Federal Court of Australia (2009). Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution. p.97.

[36] Pinto, J. (2000). Peacemaking as ceremony: The Mediation model of the Navajo Nation. International Journal of Conflict Management, 11(3), 267.

[37] Bauman, T. and Williams, R. (2004). Indigenous decision-making and disputes in land.

[38] Federal Court of Australia (2009). Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution. p.37.

[41] Recommendation adopted from Bauman, T. (2006). Waiting for Mary. p.4.

[42] Victor, W. (2007). Alternative DR (ADR) in Aboriginal Contexts.

[43] Jones, C. (2002). Aboriginal boundaries.

[44] Bell, C., & Kahane, D. (Eds.). (2013). Intercultural DR in aboriginal contexts. Vancouver: UBC Press. p.12.

[46] Jones, C. (2002). Aboriginal boundaries.

[48] Federal Court of Australia (2009). Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution. p.39.

[49] LeBaron, M. The alchemy of change: Cultural fluency in conflict resolution. In Coleman, P., Deutsch, M. & Marcus, E. Eds. The Handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice. San Francisco, USA. pp. 581-603.

[51] Federal Court of Australia (2009). Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution p.101