by Gregory Radisic

1. Background

Innovations in space technologies are increasing the accessibility of space exploration and exploitation. From a billionaire space race1 to a risky Russian military satellite test causing the increase of orbital debris to an unprecedented level,2 this year has witnessed some of the most dynamic and rapid developments in outer space policy, governance, and diplomacy since the 1960s. Space also has become more crowded than ever, with both national and commercial space actors competing for increased access to space. In fact, the United Nations Register of Objects Launched into Outer Space now contains over 9,500 objects in orbit, of which more than 20 percent were launched in the last six years.3

With the dawn of space tourism and pilotless space craft technologies, commercial space actors are growing in prominence due to the expediency by which they can complete complicated missions. However, these corporations often do not feel obligated to follow international law and custom. A recent space law workshop over the national authority to sanction space mining – which brought together both governmental and private industry space professionals in dialogue – exposed the rift between public and private entities on what laws and regulations must be followed. “Spirited debate” ensued after many private entities advocated for self-serving interpretations of over 50 years of space law precedent, including arguing that newly implemented national space mining laws superseded the rules created through international space treaties.4 Regardless of which rules will ultimately prevail and become norms within the international community, the current consensus is that the long-term operational plans of many commercial space companies fall within grey areas of the law, since their specific international legal obligations have been left uncertain. This uncertainty has brought many to call for additional concrete and specific treaties that encompass new technological developments in space and future perceived innovations, since the original space treaties were agreed to at the dawn of the space age.

Arguably, if legal scholarship and multilateral treaty building do not fill the gaps in the law, private industry will. An example can be found with SpaceX, currently the largest private space company, which has been criticized for conducting risky and abnormal space faring activities with the perceived intent to argue customary norms in any future disagreements. In 2019, SpaceX declined to alter the orbital path of its new Starlink-satellite constellation, even though it was at risk of collision with a European Space Agency (“ESA”) satellite’s well-established orbital path.5 In December 2021, Josef Aschbacher, the ESA Director General, warned that commercial space actors are being allowed to “make the rules” in space.6 Highlighting Elon Musk’s recent activities through his company SpaceX, Aschbacher warned that:

“You have one person owning half of the active satellites in the world. De facto, he is making the rules. The rest of the world including Europe … is just not responding quick enough. At the speed he is putting [objects] into orbit, he is almost owning those orbital-planes, because no one can get in there. He is creating a Musk-sovereignty in space.”7

As Earth is entering an age where, regardless of qualifications or intentions, humans can venture out into the beyond, it will not be scientific curiosity that is driving space missions, but commercial profits. Commercial actors are increasingly leading their own space missions without heavy governmental oversight, and the need for clear international guidelines and regulations has become increasingly necessary. Clearly, as space is continually explored and developed, the need exists for more robust, universally accepted outer space rules and regulations in order to deconflict space activities. Not only to prevent conflict between nations, but to also prevent conflict between these nations and the commercial space industry.

2. The Asteroid Rush: An Opportunity with Astronomical Potential

In this paper, it will be argued that there is a demonstrated need for a stable legal framework that regulates and encourages the responsible exploitation of resources from celestial bodies – one that serves to benefit all humanity. First, an assessment will be conducted of the current international legal frameworks that exist for asteroid mining, the merits of establishing a new exploitation framework similar to current deep-sea mining legislation will be explored, and finally a future model for space mining regulation will be suggested. For the sake of brevity, the example of asteroid mining activities will be this argument’s primary focus, however many of these principles may also be extended for Lunar or Martian purposes.

While space mining is a seemingly farfetched concept for most, currently Earth-bound mining companies have begun to show interest, especially in light of the potential profits. Many asteroids have regular orbits that allow them to pass between Earth and the moon. One such asteroid, the Ryugu-Asteroid, passes Earth with a minimum distance of 95,400 km. This distance sounds vast, however it is only equivalent to 0.23 lunar distances. Considering that there are five nations currently planning moon missions, landing on an asteroid like Ryugu would require significantly less fuel to get to and yield significantly more profit (~US$ 82 billion).8 Ryugu is an example of only a single asteroid, of which there are 600,000 orbiting within accessible distances from Earth.9 According to NASA’s Asterank Database, 711 of these known and accessible asteroids have a value exceeding $100 trillion each.10

There is also another perceived benefit to asteroid mining: an increased supply of critical and strategic minerals. Asteroids are brimming with many of the rare minerals that today’s technologies depend on – minerals that are being quickly depleted. Not only would asteroids serve as a solution to their terrestrial depletion, but whichever economy has primary access to these minerals would no doubt wield significant power over much of the world’s economies.11

With the current rate of technological space development, scholars have predicted that the world is on the cusp of a 21st Century economic boom that many have deemed the “asteroid-rush.”12 Billionaire investors and governments are already pouring funds into companies like Planetary-Resources, an asteroid mining start-up which has financial backing from Virgin Galactic,13 Google, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, and even filmmaker James Cameron.14 Even many upcoming space missions, including those to the moon, cite the need to exploit space-based resources to support their missions or for research and analysis back on Earth.15 Even with technological challenges still left unsolved, the next decade will more than likely witness the first commercial space-mining operations.16 For the prevention of conflict, it is more important than ever that clear guidelines to any space-based mining activities are agreed to by the international community.

3. Current International Space Treaties and Agreements

An open letter signed by 142 space professionals recently urged the United Nations to quickly begin work on a “Multilateral Agreement on Space Resource Utilization.”17 While several outer space treaties currently exist to encourage multilateral cooperation for the exploration and peaceful uses of outer space, unfortunately none explicitly create a unified and multilateral framework for mining rights to resources in outer space. The relevant international agreements as they relate to mining space resources are outlined below.

3.1 The "Outer Space Treaty" of 1967

The "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies Activities" (the “Outer Space Treaty”) creates a basic international legal framework to promote the peaceful and cooperative uses of space. It was agreed to on a large scale with 111 nations, including all space-faring nations, being parties to it.18 This treaty is broad in scope and covers the military uses of outer space, contains space object liability provisions, and stipulates the right to the free travel of space by all nations for exploratory and scientific purposes. However, only three provisions carry potential impacts on a future outer space mining operation: Articles I, II, and IX.

Article I states that:

“The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.”19

Article II states that:

“Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”20

Article IX states that:

“State Parties to the Treaty shall pursue studies of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, and conduct exploration of them so as to avoid their harmful contamination… If a State Party to the Treaty has reason to believe that an activity or experiment planned by it or its nationals in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, would cause potentially harmful interference with activities of other States Partiesin the peaceful exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, it shall undertake appropriate international consultations before proceeding with any such activity or experiment.”21

Legal scholars at the McGill Institute of Air and Space Law argue Articles I and II preclude a single nation from being the sole beneficiary of space mining profits due to the articles’ emphasis on the benefit for all humankind.22 Article II could even prohibit the staking of a mining claim, as this would carry quasi-sovereign rights like the sole use over an unclaimed area for a mining site. As noted previously, the Ryugu Asteroid is an example of a highly profitable near-Earth object. This asteroid is extremely dense and only a few kilometers in diameter.23 Staking a mining claim of a comparable size on Earth has often occurred through large-scale mining operations, however issuing property rights in space, including exclusive use rights, could create significant tension with Article II of the "Outer Space Treaty" and go against its non-appropriation principle.24

That being said, perhaps if the entirety of an asteroid will be depleted, sovereignty is less of an issue. If space mining equipment is categorized only as an extension of a nation’s spacecraft, then perhaps asteroid mining could occur in space without the need for claiming sovereignty or international consultation. Arguably similar space-based mining has already occurred without consultation with the United Nations, as the United States has already mined and brought to Earth approximately 842lbs of lunar rocks and soil over the course of six lunar missions.25

Meanwhile, Article IX of the "Outer Space Treaty" could be interpreted as, if the mining activities do not create harmful contamination in space and do not harm the activities of other Member States in space, then a mining operation can go ahead without the consultation of the international community.26 The definition of “harmful contamination” in space may be an extremely high threshold to meet and may even be restricted to larger celestial objects such as quasi-habitable moons and planets. Especially in the case of asteroids, these are often highly radioactive rocks with little discernable environmental features to protect. To harmfully contaminate asteroids would likely be extremely difficult.

Additionally, the complete depletion of asteroids in near-Earth orbit may even be in the best interest of all humankind, as these rocks can pose the threat of impact with Earth.27 Asteroid mining could be considered orbital debris hazard mitigation and not a meaningful contamination of the outer space environment.

Regardless of one’s interpretation of the "Outer Space Treaty" in relation to asteroid mining, it is clear that the legal debate surrounding the mining of space resources still lacks consensus or clarity on an international scale, even with the highly agreed upon and ratified "Outer Space Treaty".

3.2 The “Moon Agreement” of 1979

The "Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies" (the “Moon Agreement”) sought to reaffirm provisions within the "Outer Space Treaty" while attempting to prevent any commercial exploitation of lunar resources.28 However, the agreement is largely seen as a failure since only a small number29 of Member States were parties to and ratifiers of it – namely spacefaring nations have not signed, including the United States, China, Russia, Japan, France, and Canada.30

While some have attempted to compare the “Moon Agreement” to mining rights provided by national American legislation, the major critique of spacefaring nations was that the agreement was opposed to free enterprise and private property rights.31 Article XI of the “Moon Agreement” states that “The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind”32 and that an international regime should be established to govern the orderly and safe development, rational management, and equitable sharing of “the natural resources of the moon.”33 However, due to the lack of specificity contained within the “equitable sharing” of resources provision, the “Moon Agreement” lacked enough clarity to become practical for capitalist space-faring countries to accept. Nonetheless, the “Moon Agreement” does attempt to set an international legal precedent on the mining of resources in outer space and its failures can inform the future structure of a successfully negotiated asteroid mining legal framework.

3.3 The “Artemis Accords” of 2020

Fifteen of the world’s most prominent spacefaring nations have signed the US-led "Lunar Gateway Treaty" (the “Artemis Accords”) since its inception in October 2020.34,35 The “Artemis Accords” cover a variety of topics from inter-governmental transparency through data sharing, to the protection of space heritage sites, the registration of lunar technologies deployed, and indeed the use of space resources. While the provisions regarding uses of the moon have been emphasized in the press, the byline of the treaty states “Principles for Cooperation in the Civil Exploration and Use of the moon, Mars, Comets, and Asteroids for Peaceful Purposes.”36 Therefore, more broadly, asteroid exploration and mining is indeed encompassed within the “Artemis Accords”.

The “Artemis Accords” are a series of bi-lateral agreements with NASA and were not signed through any United Nations entity. However, the Accords outline that space resource extraction and utilization can and will be conducted following the pre-existing rules set out in the "Outer Space Treaty". Specifically, the ability to extract and utilize resources on the moon, Mars, and asteroids is emphasized in the “Artemis Accords” under Articles II, VI, and XI of Section 10 and Article VI of Section 11.

At face value, it would seem the “Artemis Accords” conflict heavily with the non-appropriation principle and province of all mankind principles set out in the "Outer Space Treaty". The authors of the “Artemis Accords” have attempted to reconcile any perceived conflict between the "Outer Space Treaty" and the “Artemis Accords” through Article II of Section 10. This article is controversial as it attempts to create a new, internationally recognized interpretation of the "Outer Space Treaty" by stating:

“The Signatories emphasize that the extraction and utilization of space resources, including any recovery from the surface or subsurface of the moon, Mars, comets, or asteroids, should be executed in a manner that complies with the "Outer Space Treaty" and in support of safe and sustainable space activities. The Signatories affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the "Outer Space Treaty", and that contracts and other legal instruments relating to space resources should be consistent with that Treaty.”37

Scholars have argued that the insertion of the above article shows that the US is trying to become the global regulator of commercial space activity, as opposed to following the global spirit of the "Outer Space Treaty".38 An article published in the journal "Science" by two Canadian space experts argues an American-centric and capitalist approach is likely to create rampant exploitation of space resources at the expense of science.39 It claims that America is successfully leveraging partnership agreements, alongside lucrative financial contracts and access to NASA technologies, to reinforce its own political agenda with regards to the "Outer Space Treaty".40 Others argue that this American attempt to sculpt the interpretation of international space law through the “Artemis Accords” is another reason why existing treaties, such as the “Moon Agreement” and "Outer Space Treaty", should be amended to have specific stipulations and procedures surrounding mining rights.41

An additional property rights consideration is found under Article VI of Section 11. This article proposes the creation of “safety zones” surrounding national outposts and commercial space operations with the goal of preventing harm or interference from rival countries or companies operating in close proximity.42 The issue is that these “safety zones” would also operate similar to the ownership of lunar property and provide the respective nation with exclusive uses to a specific extraterrestrial area.43 Likely, this would be in contravention of the ban against exclusive use, colonization, and the of claiming extraterrestrial sovereignty as laid out in Article II of the "Outer Space Treaty".44

4. UNCLOS as an Analogous Framework: Can the Solutions to a Successful Asteroid Mining Agreement be Found in the Deep-Sea Mining Regiment?

4.1 The Deep-Sea Mining Regime as a Useful Space Mining Model

After an assessment of relevant international space treaties, clearly there are still contentious debates surrounding any future asteroid mining operations. Mainly is it even a possibility to create an asteroid mining regime that still aligns with the "Outer Space Treaty"’s heavily agreed upon non-appropriation and province of all mankind principles. Spacefaring nations and commercial space actors both have interests that seem to inherently contradict these foundational principles in the "Outer Space Treaty" and, as a result, both are attempting to mold very specific interpretations that may not fall within the spirit of this 50-year-old document. Significant tensions could be created with developing nations who are new entrants into the outer space domain and desire that the spirit of the original "Outer Space Treaty" is honoured. Therefore, it is important to explore how space mining could coexist with the current outer space legal framework in a complimentary fashion to avoid future escalations and conflict in space.

The law of the sea may be a useful lens through which to study and craft future space mining legislation. The law of the sea has historically faced many similar issues and concerns as the legal framework governing the world’s second largest global common and holds significantly more historical jurisprudence to draw from. The sections below will assess the merit of using the law of the sea’s deep-sea mining regiment as an analogous legal framework to inform future asteroid mining laws.

4.2 The International Seabed Authority

The "United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea" (“UNCLOS”), which came into force in 1994, establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities including the codification of international law regarding territorial waters, sea lanes, ocean resources, and deep-sea mining.45 The "International Seabed Authority" (“ISA”) is also established under “UNCLOS” Art.156(1) and is tasked with approving and overseeing the deep-sea mining activities occurring in international waters, as well as allocating a significant amount of the profits from deep-sea mining in international waters to developing countries.46

Three bodies form the ISA: the Assembly, the Council, and the Legal and Technical Committee.47 All three bodies operate through consensus with decisions being made using a practical, science-based approach.48 “UNCLOS” Art.156(2) states that all Member States that are parties of “UNCLOS” are ipso facto members of the ISA. As a result, at the beginning of 2022, there were 168 state members of “UNCLOS” which actively contribute to the ISA and its governing bodies.49

The ISA was created out of a recognized need for international administration over mining activities beyond sovereign jurisdictions. Specifically, deep-sea mining is defined as “mining taking place outside of the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone of states.”50 Prospectors and investors alike began frantically exploring the opportunity of deep-sea mining after a 1965 study claimed that an almost inexhaustible supply of nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese existed on the deep-sea bed of the Pacific Ocean.51 Regardless of the technological gap that existed in the 1960s, many prospectors saw the ocean floor as a way to consolidate control over massive reserves of critical and strategic minerals – not unlike the celestial prospectors of today.

Deep-sea mining involves the retrieval of minerals and deposits from the ocean floor at a depth of at least 200m. Of the three existing categories of deep-sea mining – polymetallic nodule mining, polymetallic sulphide mining, and the mining of cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts – the most profitable and economically sound option is mining for polymetallic nodules.52 As a result, the “majority of proposed deep-sea mining sites are near polymetallic nodules or active and extinct hydrothermal vents at 1,400m to 3,700m below the ocean’s surface.”53 No commercial deep-sea mining operation has ever went ahead since there are significant technological and environmental hurdles to overcome prior to mining at these depths. That being said, the world is coming close to surmounting these barriers and, as a result, the ISA has entered into 15-year contracts for deep-sea mining exploration with 22 contractors.54 These contractors represent an eclectic mix of governments, state-owned companies, and private corporations – showing the diversity in worldwide interest over deep-sea mining in the near future.55

4.3 The Common Heritage of Mankind Principle

What makes the ISA exceptionally unique is that it is guided by the principle of “common heritage of mankind” (“CHM”) which is an essential element of “UNCLOS”. The CHM principle exclusively applies in relation to the regulation and management of the resources which lie outside the limits of national jurisdiction.56

“UNCLOS” does not explicitly give a definition of the CHM principle, but instead outlines two main characteristics. First, the CHM principle applies to the entirety of the international seabed area57 and its resources (the “Area”),58 which are defined as “all solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources in situ in the Area at or beneath the seabed.”59 It is estimated that the Area and all its mineral resources encompasses approximately 54 percent of the world’s oceans.60 Secondly, the CHM principle needs to be understood as having a universalist intention, designed to support the ultimate objective to achieve a more egalitarian society – an objective that is a shared responsibility on all Member States and organisations.61 Yu and Ji-Lu state that “Safeguarding the common heritage of mankind is the common responsibility of the international community.”62 This means that both landlocked and coastal states have a shared responsibility to protect the Area from unlawful mining infringements that do not duly adhere to the mining regiment outlined by the ISA.

In short, the CHM principle means that equity amongst all nations over the benefits derived from resources in this global common is placed at the forefront of all commercial mining activities – mainly through a profit-sharing scheme for developing and landlocked nations.63

In line with the CHM principle, “UNCLOS” Arts.82(4), 160(2)(f)(i) and 162(2)(o)(i) contain the provisions related to equitable sharing payments derived from the exploitation of resources on the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. Under “UNCLOS” Art.82, the rate of payments will annually rise from one percent at the commencement of exploitation to seven percent of the value or the volume of production at the site by the twelfth year. Notably, developing states that are net importers of a mineral resource produced from its continental shelf are exempt from these payments.64 Under Art.82, the ISA’s role is to serve as a conduit for payments, with the priority of profit distribution occurring to “the least developed and land-locked” states.65

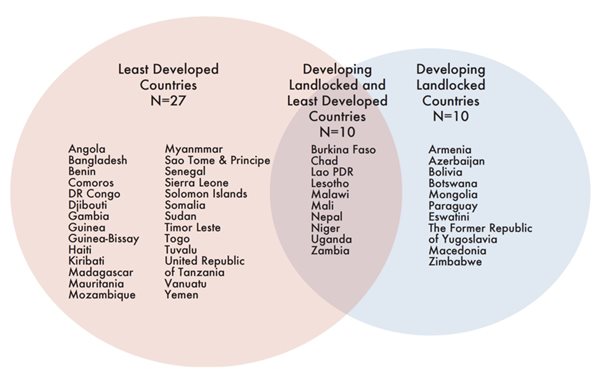

Within “UNCLOS” Art.160(2)(f)(i), which is directed at the ISA Assembly, and “UNCLOS” Art.162(2)(o)(i), which is directed at the ISA Council, the ISA is given the ability to consider and approve the rules, regulations, and procedures on the equitable sharing of financial and other economic benefits derived from activities in the Area. All “UNCLOS” party states jointly will decide the priority order by which Member States will receive the equitable sharing payments. This list has yet to be finalized, however a suggested draft list was published in the "ISA Technical Study No. 31 on the Equitable Sharing of Financial and other Economic Benefits from Deep Seabed Mining".66 See Figure 1 below for the current draft list.

Figure 1. Proposed List of Least Developed and Landlocked Developing Countries

4.4 The Mining Code: A Work in Progress

The Mining Code (the “Code”) refers to the comprehensive set of rules, regulations, and procedures issued by the ISA to regulate prospecting, exploration, and exploitation of marine minerals in the Area.67 All rules, regulations, and procedures are issued within the general legal framework established by “UNCLOS” – namely through “UNCLOS” Part XI and its 1994 Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of “UNCLOS”.68

While the Code’s exploration regulations have been finalized, the ISA is still developing its regulations governing the exploitation of mineral resources. This process began in 2014 with a series of scoping studies and has culminated in the July 2019 "Draft Regulations on Exploitation of Mineral Resources in the Area" (“Draft Regulations”), published by the ISA Legal and Technical Committee following a series of broad consultations.69 Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the draft exploration regulations are estimated to be finalized by the ISA Council and then the ISA Assembly sometime between 2023-2024. This must occur before any contract for mineral exploitation can be issued.

The “Draft Regulations” aim to balance stringent global environmental regulation, commercial economic profits, and its “equitable sharing criteria” which requires a portion of the financial rewards and other economic benefits from mining to be paid to the ISA to then be shared.70 The requirement for contractors to pay a bi-annual royalty to the ISA is enshrined in “Draft Regulations” Regs.64 and 67.

According to Reg.71, the royalty can be based off a variety of measurements such as the quantity of mineral-bearing ore extracted in wet metric tons, the market value of ore extracted, and/or a combination of other factors the ISA sees as reasonable. Penalties for a lack of payment include a five percent annual interest fee on payments owed71 and, in the case of any violation of an exploitation contract, additional monetary penalties “proportionate to the seriousness of the violation.”72

Inspection, compliance, and enforcement measures for the ISA are governed mainly by “Draft Regulations” Regs.96-105, which give the ISA the power to inspect and audit contractors for compliance, issue and enforce penalties, terminate exploitation contracts, and even take emergency remedial actions at the cost of the contractor when necessary in order to preserve the marine environment.73

5. Asteroid Mining Legal Framework Proposal

5.1 Arguments Against Modelling Space Mining Legislation after the ISA Deep-Sea Mining Regulatory Framework

The main critique against modelling any celestial mining framework after the deep-sea mining framework created through “UNCLOS”, is that it is seen as largely incompatible with the ideals of capitalist-based nations. Namely, the United States has refused to ratify “UNCLOS”, due in part to the equity sharing provisions in Part XI, which it states is not free-market friendly, contrary to their security interests, and largely designed to favor the economic systems of Communist states.74 That being said, even if a few nations disagree, arguably it is better to have consensus amongst the remaining 157 signatory nations instead of forfeiting global consensus entirely. Even the United States has slowly crawled towards ratifying “UNCLOS” – with the subsequent Bush75 and Obama76 presidencies both pushing for its ratification – and, nonetheless, the United States still recognizes “UNCLOS” as a codification of customary international law.77 There is something to be said for ratifying a large-scale space mining treaty and keeping the door open for those who disagree to join once it becomes in their best interests to adhere to a clear international legal framework.

Another critique of including the “UNCLOS” CHM principle within a space-based treaty is that it has been tried before through the failed “Moon Agreement”. As noted earlier, the “Moon Agreement” was not ratified by any state that engages in self-launched human spaceflight and, therefore, has little relevancy within the current international framework of space law.78 However, the space ecosystem in the 2020s looks much different than the 1970s, when the USSR and USA were the main space actors. There are now more than 25 countries capable of human spaceflight, close to 10,000 human-made spacecraft in orbit, and over 120 nations operating space-based technologies in the form of satellites.79 With nations increasingly prioritizing the ability to access space using their indigenous space programmes, perhaps the world has reached a minimum threshold to gain momentum for the CHM principle.

An additional critique of mirroring the “UNCLOS” mining framework is that its equity sharing provisions have been largely untested. Since the ISA’s “Draft Regulations” on exploitation of deep-sea minerals is still in its infancy, this framework for regulating mining activities within a global common could be viewed by nations as being largely untested – especially since the actual profit sharing mechanisms have not begun. Thus, nations would be hesitant to follow the “UNCLOS” framework with no idea of what unforeseen issues exist. For example, the ISA’s enforcement, inspection, and penalty mechanisms have also been largely untested. It is uncertain how enforcement and penalties through the ISA’s decision-making bodies would interplay with the world’s increasingly interconnected economies. Nations that sit on the ISA Assembly and ISA Council could be vulnerable to external influences in their penalty decisions. Hypothetically, not much would prevent more developed nations like China from openly or covertly threatening sanctions against nations that side against them in ISA disputes. That being said, the ISA mining framework has created a uniform and manageable system through which all nations can come together to shape policy and governance over the mining of deep-sea resources. This is contrasted heavily with the largely unregulated scramble to access, explore, and exploit outer space for its celestial resources. Again, perhaps an imperfect and untested system for regulation and enforcement of space mining norms, which could be updated overtime, is better to implement than nothing at all.

5.2 An Ideal Framework for Asteroid Mining80

Under the auspices of the "Outer Space Treaty", a central authority that regulates the commercial exploitation of celestial mining should be established (hereafter the “Authority”). The Authority, similar to the ISA, should be given autonomy from the United Nations Assembly to oversee all activity and similarly be composed of an Authority Assembly, Authority Council, and Authority Legal and Technical Committee. All members of the "Outer Space Treaty" should ipso facto become members of the Authority and, thereby, have a say in shaping the future of celestial mining laws.

As noted earlier, one of the key tenants of the "Outer Space Treaty" is the principle that outer space is the “province of all mankind.” An ideal framework would include the province of all mankind (“POAM”) principle. The currently undefined POAM principle would continue to be considered to be a separate and distinct legal principle from the “UNCLOS” CHM principle. Therefore, a need would exist for a clear definition to be universally agreed upon by all signatories of the "Outer Space Treaty". This agreed upon definition of the POAM principle should serve as the cornerstone for all future regulation and commercial development.

While perhaps idealistic, egalitarianism should be placed at the forefront of this definition. While the notion of equitable profit sharing may be contrary to many nations’ ideological beliefs, perhaps reframing the issue as simply a mining levy for the issuance of mining rights within the global commons would be sufficient. Most national mining legislation requires the compensation of surface landowners for any inconvenience for mining activity.81 A similar compensation process by the Authority, which could provide leases for commercial mining exploration and exploitation, would allow for all Member States to be compensated for the commercial use of outer space, in line with the POAM principle. These profits, in turn, could be redistributed as the Authority sees fit. Additionally, the CHM principle’s notion of profit sharing could be reimagined within the POAM principle’s framework. POAM inherently means that all nations have the right to access and use space. Perhaps creating capacity building models for developing or non-spacefaring nations, through the sharing of technology and expertise, could serve as useful alternatives or supplements to any financial redistribution scheme from leasing profits.

Once the foundational tenants and overarching structure of the Authority are established, then working groups within the Authority can be tasked to establish codes and regulations for the exploration and exploitation of asteroid resources. Similar to the ISA’s process, these working groups should be given strict timelines to adhere to for the creation of regulation so that commercial exploration and exploitation can continue to advance at an acceptable rate. The “Artemis Accords” state that “extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the "Outer Space Treaty".”82 In this way, nations can have authority over the equipment and crafts they place on celestial bodies, without claiming sovereignty over the land on which it sits. This is likely an essential element for working groups to agree upon so that nations who are signatories of the “Artemis Accords” are willing to adhere to a United Nations based regulatory scheme.

5.3 A Final Note: Why Implement Regulation Before Celestial Mining Commences?

More likely than not, the Mining Code’s regulations on the exploitation of deep-sea minerals will be finalized in the coming years and the first commercial deep-sea mining operations will commence soon after. Especially half a century ago, the technological side of deep-sea mining operations seemed inaccessible, generally unprofitable, and likely unachievable. Yet the international community did not shy away from pre-emptive deep-sea mining law making and recognized the potential conflict that could ensue following a lack of deep-sea mining regulation. Now, with the world at the cusp of beginning deep-sea mining operations, this lengthy process has objectively paid off. Governments and companies did not rush to make claims over or begin mining of the deep-sea, creating environmental or geopolitical problems in their wake, but instead have complied with the ISA and their orderly procedures.

Ultimately, the biggest historical take-away from the ISA’s deep-sea mining framework is that even basic regulation of a global common is better than a complete lack thereof. A 2018 attempt by the United Nations to produce consensus on a framework of laws for the sustainable development of outer space through COPUOS failed, in part, due to the chief US negotiator declaring that negotiations of the rules of the international regime should be delayed until the feasibility of exploitation of lunar resources has been established.83,84 Frankly, a lack of foresight over future mining technology is a lazy argument for a failure to implement a basic asteroid mining framework, especially in light of how the “UNCLOS” mining regime has progressed and developed. A basic celestial mining regulatory solution would create some semblance of order, instead of the wild-west cowboy mentality currently taking place by commercial and governmental actors – with the added benefit of being able to be revisited and amended over time as needed. This application would be ‘one small step for man’ towards a unified international legal framework that aligns with the spirit of the "Outer Space Treaty" at both the national and international levels, and would ‘go where no man has gone before’ by creating a clear basis for the mining of critical and strategic minerals in outer space.

Bibliography

A. Ahnert, and C. Borowski, “Environmental risk assessment of anthropogenic activity in the deep-sea”, Journal of Aquatic Ecosystem Stress and Recovery (2000) 7 (4): 299–315, online (pdf).

Aaron Boley, and Michael Byers, “U.S. policy puts the safe development of space at risk” Science (09 Oct 2020) Vol 370, Issue 6513, pp 174-175, online (pdf).

“About ISA”, International Seabed Authority (2021), online.

“Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, 5 December 1979, A/RES/34 (LXVIII) (entered into force 11 July 1984), online (pdf): [Moon Agreement].

Alex Knapp, “Asteroid Mining Startup Planetary Resources Teams with Virgin Galactic”, Forbes (11 June 2012), online.

Andrew Zaleski, “How the space mining industry came down to Earth”, Fortune (24 November 2018).

“Asteroid Mining Venture Backed by James Cameron, Google CEO Larry Page”, CBS News (24 April 2012), online.

Alex Gilbert, “Mining in Space is Coming”, Milken Institute Review (26 April 2021), online.

Bob Daemmrich, “Russia Compares Trump’s Space Mining Order to Colonialism”, The Moscow Times (7 April 2020) online.

Bob McDonald, “Canada just signed a new moon pact – is it a good idea?”, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (16 October 2020) online.

Canadian Space Agency, “A Canadian astronaut will fly to the Moon – Canada signs a historic space treaty with the U.S. and secures a vital role for Canada in the Lunar Gateway”, Government of Canada (16 December 2020), online.

CBC News, “Western profs to explore laws and regulations for mining in outer space”, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (7 February 2021), online.

Christopher Newman, “Artemis Accords: why many countries are refusing to sign Moon exploration agreement”, The Conversation (19 October 2020), online.

Curation Lunar, “Lunar Rocks and Soils from Apollo Missions”, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (1 September 2016), online.

Debra Werner, “Space Law Workshop exposes rift in legal community over national authority to sanction space mining”, SpaceNews (17 April 2018), online.

Dennis C. O’Brien, “Beyond UNISPACE: It’s time for the Moon Treaty” Pace Review (21 January 2019), online.

“Draft Regulations on Exploitation of Mineral Resources in the Area – ISBA/25/C/WP.1”, International Seabed Authority (July 2019), online (pdf), [Draft Regulations].

Elham Shabahat, “A Mining Code for the Deep Sea”, Hakai Magazine (25 June 2021), online.

“Exploration Contracts”, The International Seabed Authority (2021), online.

Ezzy Pearson, “Space Mining: The New Goldrush”, BBC Science Focus (11 December 2018), online.

George W. Bush, “President’s Statement on Advancing U.S. Interests in the World’s Oceans”, Whitehouse National Archives, (15 May 2007), online (pdf).

G. P. Glasby, “Deep Seabed Mining: Past Failures and Future Prospects”, Journal of Marine Georesources & Geotechnology (2002), 20 (2): 161-176, online (pdf).

Jackie Wattles et al., “The Oldest and Youngest People to Travel to Space Just Made History”, CNN Business (20 July 2021), online.

Joey Roulette, “Exclusive: Trump administration drafting ‘Artemis Accords’ pact for moon mining – sources”, Reuters (5 May 2020), online.

J. L. Mero, “The Mineral Resources of the Sea”, Elisevier (1965), print.

Jonathan O’Callaghan, “NASA Mission Could Blast an Asteroid That Once Menaced Earth”, The New York Times (15 December 2021), online.

Jonathan O’Callaghan, “SpaceX Declined To Move A Starlink Satellite At Risk Of Collision With A European Satellite”, Forbes (2 September 2019), online.

Jonathan Sydney Koch, “Institutional Framework for the Province of all Mankind: Lessons from the International Seabed Authority for the Governance of Commercial Space Mining” Astropolitics (2008), 16:1, 1-27, online (pdf).

Joseph Crombie, “Legislating for Humanity’s Next Step: Cultivating a Legal Framework for the Mining of Celestial Bodies.” Journal of Space & Defense (2017), Vol. 10, Issue 1: pg 9-24, online (pdf).

J. Yu, and W. Ji-Lu “The Outer Continental Shelf of Coastal States and the Common Heritage of Mankind”, Ocean Development & International Law (2011), 42 (4): 317-328, online (pdf).

Khaled Abdel-Barr, and Karen MacMillan, “The International Comparative Legal Guide on Mining Laws and Regulations”, Global Legal Group (2021), online.

Kylie Atwood et al., “US says it ‘won’t tolerate’ Russia’s ‘reckless and dangerous’ anti-satellite missile test” CNN Politics (16 November 2021), online.

Marie Bourrel, et al., “The Common of Heritage of Mankind as a Means to Assess and Advance Equity in Deep Sea Mining” (2016) Int’l J of Ocean Affairs, online (pdf).

M. W. Lodge, “International Seabed Authority’s Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in the Area”, Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law (2002),20 (3): 270-295, online (pdf).

Peggy Hollinger, and Clive Cookson, “Elon Musk being allowed to ‘make the rules’ in space, ESA chief warns”, The Financial Times (6 December 2021), online.

Roger Rufe, “Statement of the President of the Ocean Conservancy before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations”, Committee on Foreign Relations (21 October 2003), online (pdf).

Simonetta Di Pippo, “Keynote Address”, SATELLITE 2021 Global Conference (delivered on 10 September 2021), speech.

“Space Mining: Are We on the Cusp of an Asteroid Rush?” The Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan (2020), online.

“Status of International Agreements relating to activities in outer space as at 1 January 2021”, United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (31 May to 11 June 2021), online (pdf).

Surface Rights Act, RSA 2000, c S-24.

“The Artemis Accords: Principles for Cooperation in the Civil Exploration and Use of the Moon, Mars, Comets, and Asteroids”, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, United States of America, 13 October 2020 (entered into force 13 October 2020), online (pdf)

“Technical Study No. 31 on the Equitable Sharing of Financial and other Economic Benefits from Deep-Seabed Mining”, International Seabed Authority (2021), online (pdf).

“Testimony of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on the US National Security and Strategic Imperatives for UNCLOS Ratification”, US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (23 May 2012).

Tijjani Muhammad-Bande, “International Open Letter on Space Mining”, The Outer Space Institute of the University of British Columbia (31 August 2020), online.

“The Mining Code”, International Seabed Authority (2021), online.

“Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, 19 December 1966, A/RES/2222 (XXI) (entered into force 10 October 1967), Art I [Outer Space Treaty].

“United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”, 10 December 1982 (entered into force 16 November 1994) [UNCLOS], at Art 1(1)(1).

Vidvuds Beldavs, “Simply fix the Moon Treaty”, The Space Review (15 January 2018), online.

“What Kind of Asteroid is Ryugu?” Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (4 April 2018), online.

Endnotes

3 Simonetta Di Pippo, “Keynote Address”, SATELLITE 2021 Global Conference (delivered on 10 September 2021), speech.

9 See

Asterank, a scientific and economic-database that compiles data from the NASA Jet-Propulsion Laboratory’s

Small-Body Database and the

Minor-Planet-Center to rank asteroids by likely potential value, cost-effectiveness for mining, and other metrics [AsteroidRank].

19 Emphasis added; “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, 19 December 1966, A/RES/2222-(XXI) (entered into-force 10 October 1967), Art.I [Outer-Space Treaty].

20 Emphasis added;

Ibid, Outer-Space Treaty, Art.II.

21 Emphasis added;

Ibid, Outer Space Treaty, Art.IX.

23 Supra note 9, AsteroidRank.

29 Only 11 nations are party to the Moon-Agreement.

30 Supra, note 28, Moon-Agreement.

31 Vidvuds Beldavs, “

Simply fix the Moon-Treaty”, The Space Review (15 January 2018), online; See also, U.S. Congress, “Senate, Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee of Commerce, Science, and Transportation”, Hearings, 96

th – Congress, 2

nd session, 1980.

32 Supra note 28, Moon-Agreement, Art.XI, s.1.

33 Supra note 28, Moon-Agreement, Art.XI, s.7.

36 Supra, note 34, Artemis-Accords, at pg.1.

37 Supra, note 34, Artemis-Accords, Art.VI, s.11.

42 Supra, note 34, Artemis-Accords, Art.VI, s.11.

44 Supra, note 19, Outer Space Treaty, Art.II.

45 “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”, 10 December 1982 (entered into force 16 November 1994) [UNCLOS], at Art.1(1)(1).

46 Ibid, UNCLOS, Art.156 (1).

47 “

About-ISA”, International Seabed-Authority (2021), online.

51 J.L. Mero, “The Mineral Resources of the Sea”, Elisevier (1965), print.

52 “Exploration Contracts”, The International Seabed Authority (2021), online.

57 Supra, note 45,

UNCLOS, Art.1(1)(1).

58 Supra, note 45, UNCLOS, Art.136.

59 Supra, note 45, UNCLOS, Art.133(a).

60 Joseph Crombie, “Legislating for Humanity’s Next Step: Cultivating a Legal-Framework for the Mining of Celestial Bodies.” Journal of Space & Defense (2017), Vol.10, Issue 1: pgs.9-24, online (pdf).

61 Supra, note 45, UNCLOS, Art.139.

64 Supra, note 45, UNCLOS, Art.82(3).

65 Supra, note 45, UNCLOS, Art.82(4).

68 Supra, note 45, UNCLOS, Part XI.

71 Supra, note 69, Draft-Regulations

, Reg. 79.

72 Supra, note 69, Draft-Regulations

, Reg. 80.

73 Supra, note 69, Draft-Regulations, Regs. 96-105.

76 “Testimony of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on the US National Security and Strategic Imperatives for UNCLOS-Ratification”, US Senate-Committee on Foreign Relations (23 May 2012).

80 This is an ideal framework that is personal to me and does not reflect the opinions of the National Space Society, European Space Agency, or United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs.

81 For example, see the

Surface Rights Act, RSA 2000, S-24.

82 Supra, note 34, Artemis-Accords, Art.VI, s.11.