(disponible uniquement en anglais)

The Prospect of Public Nuisance for Indigenous Communities: The Case of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

Annie Arko, University of Ottawa

INTRODUCTION

Following a site visit to Canada in the summer of 2019, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Toxics noted that “Indigenous peoples appear to be disproportionately located in close proximity to actual and potential sources of toxic exposure.”1 The Special Rapporteur expressed particular concern about the communities surrounding the Athabasca Oil Sands, in northern Alberta.2 Taking inspiration from comments by Professors Collins and McLeod-Kilmurray that Indigenous communities may have increased success with a public nuisance claim and that nuisance is a promising area for environmental litigation,3 I will consolidate the law on public nuisance and apply it in the context of a hypothetical environmental claim by an Indigenous group affected by the Athabasca Oil Sands operations. First, I will provide an overview of the situation of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, then I will introduce the law of nuisance and assess the First Nation’s public nuisance standing. Lastly, I will determine the likely success of such a claim and briefly comment on possible defences and remedies. I will conclude with a summation of my assessment of the hypothetical claim.

I ultimately find that the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation is likely to succeed in a claim for public nuisance against upstream oil sands operators and their enabling government counterparts. I do so by taking the law on its face without proposing legal reform. However, I should note that this paper is limited to publicly available information. A case like this, in reality, would require the disclosure of many documents on discovery and further site testing for contaminants.

PART I: THE SITUATION

The Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation has used and occupied the Athabasca region for thousands of years.4 The Chipewyans’ traditional and continuing livelihood is derived from hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering from the land.5 These land-based practices are protected under Treaty 8 and are fundamental to the way the Chipewyans connect to their traditional lands and pass down their culture.6

Treaty No. 8

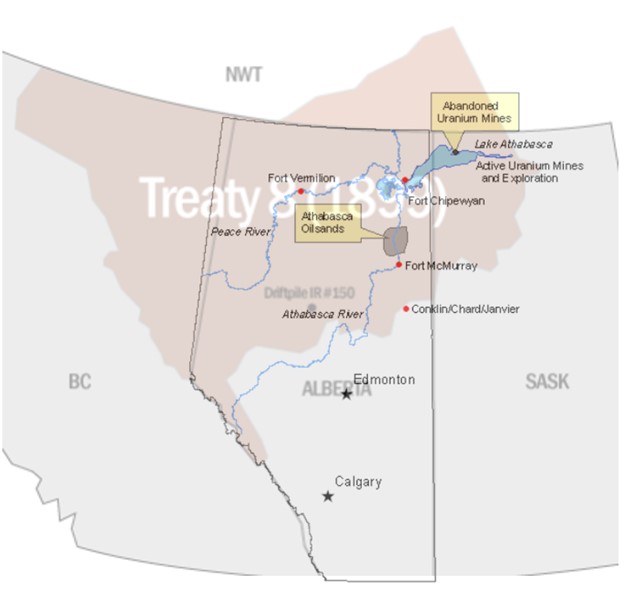

Treaty 8 was signed in 1899 by the British Crown and the Chipewyan, Cree, and Beaver Chiefs (See Figure 1).7 Under Treaty 8, the three First Nations ceded, released, surrendered, and yielded their land, rights, titles, and privileges to the Dominion of Canada.8 However, the Crown carved out the right of the First Nations to continue their “usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing throughout the tract,” and reserved land for the First Nations to live on.9

Figure 1 Geographical Overlay of Treaty 810 with Major Reference Locations in Alberta11

The Geography & Operation

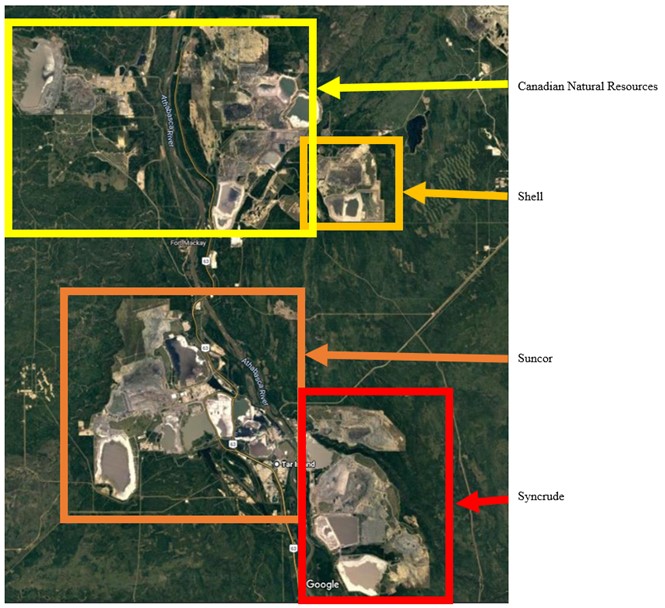

The Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation lives on designated reserves and in the town of Fort Chipewyan near where the Athabasca River meets Lake Athabasca.12 Less than 200 kilometers upstream, is the Athabasca Oil Sands, which is a deposit of bitumen, a heavy, low-grade form of crude oil, suspended between grains of sand and soil below the Boreal forest and muskeg cover.13 Four major oil companies—Suncor, Canadian Natural Resources, Syncrude, and Shell—work this area extracting bitumen via surface or in-situ mining (See Figure 2). The heavy tar-like substance that is mined is freed from the surrounding dirt and sand by being blasted with large amounts of water. The bitumen is diluted with a chemical to obtain a higher viscosity for transport and is exported out of the country to be processed and refined for use.14

Meanwhile, the water-blasted toxic liquid residue is collected in gravel filled holes in the ground called tailings ponds.15 This residue is a slurry of “water, sand, fine silts, clay, residual bitumen and lighter hydrocarbons, inorganic salts and water-soluble organic compounds.”16 Over the course of years, through sedimentation, the toxic discharge in these ponds is intended to separate from the water with gravity. Through evaporation and drainage of water, the end-state of the pond is meant to be dried discharge that can be removed so that the land can be reclaimed.17 Through the approval of the project and subsequent monitoring, companies are required to report to the Alberta Energy Regulator on the composition and stage that their tailings are in as well as how much seepage they experience and how much tailings fluids are “exiting the system.”18

The understanding and intention of the Regulator and the companies that fluid will seep out of the unlined ponds is challenging considering that tailings contain water soluble chemicals19 that will not be naturally filtered out by sand and gravel as the fluid seeps out.20 This is particularly problematic since these tailings ponds line the banks of the Athabasca River, and at their closest are a mere 70 meters from the edge of the Athabasca River. This combination of design and location of the tailings ponds increases the risk that chemicals are entering the Athabasca River.

From 2009 – 2010, several fish tissue and water samples from the Athabasca River have been found to contain elevated levels of organic acids, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals including cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, silver, and zinc. 21 At the time there was debate as to whether upstream oil production was the cause of this water contamination, since the River flows through naturally occurring bitumen deposits.22 But, regardless of any natural contamination, in 2017 it was found that the tailings ponds have been leaking 11 million litres of toxic substances into the Athabasca River every day.23 This is an increase in total contamination by oil sands operators that is additional to any natural exposure.

Figure 2 Athabasca Oil Sands Operators24

Health in Fort Chipewyan

Physical Health

In 2006, a fly-in doctor that frequently worked in Fort Chipewyan reported high numbers of unusual cancers, which prompted the Alberta Cancer Board to launch an investigation.25 Alberta’s report on cancer incidence among Fort Chipewyan residents, covering the years 1995 – 2006, found a statistically significant increase in cancer incidence for all cancers and specific statistical significance for biliary tract cancer, soft tissue cancer, and blood and lymphatic system cancer, including leukemia.26 The study also found a number of cancers that were more prevalent than expected among the people of Fort Chipewyan, but which fell below statistical significance.27 (See Appendix A for a further breakdown of incidence.)

Although media coverage focused on the potential impact of the oil sands operation on the physical health of the First Nation, in a court of law, this is one of the more difficult to prove elements of a prospective case. Why is the community’s cancer rate elevated? Were there other factors that contributed to the decreased physical health outcomes of the community? Can the specific chemicals in the tailings ponds create those specific cancers? However, significantly less difficult to prove are the psychiatric, cultural, and economic harms that the community is experiencing because of the presence and operations of the Athabasca Oil Sands operators.

Psychiatric Harm

Beyond the physical health effects, significant psychiatric harm has resulted from living with chronic exposure to toxic contaminants. An interview conducted with community members of Fort Chipewyan indicated that they were very concerned for their own health and wellbeing.28 Many reported feeling scared, anxious, and depressed for the health outlook for themselves and their community because of the high rate of cancer and the many resulting funerals in their community. Many community members said that they no longer felt safe eating the fish or hunted meat from their traditional lands because of the number of animals found with tumours and lesions.29 Lending credibility to these fears and observations, a 2014 study found that consumption of traditional meat from the area was associated with higher cancer incidence.30

Cultural Harm

Related to psychiatric harm, but worthy of a separate discussion, is the cultural and spiritual harm that the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation people are experiencing from the contamination. A cultural impact assessment conducted in 2015 identified four main categories of cultural components that are critical to the wellbeing of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation—all of which are based in land and have been affected by contamination.31 First, wellbeing is closely tied to the Chipewyans’ ability to practice their spirituality though nature, and their ability to travel over the land and water. Second, their traditional knowledge “especially as it relates to experiences on the land and the skills and knowledge required to harvest its resources” is highly valued by the community.32 Third, their ability to provide for themselves and their community through fishing, hunting, trapping, gardening and harvesting is core to their identity. Fourth, relationship building in the community via the gathering, visiting, and sharing the fruits of the land has been a long standing hallmark of their culture.33 These four corners of the Chipewyan’s identity have been muted by their inability to live safely from the land and travel to their spiritual grounds due to water quality concerns.

PART II: THE CLAIM

To date, I cannot locate any related legal filings by the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, possibly due to the community members’ employment and increasing dependence on the Athabasca Oil Sands for income. However, community desire to litigate aside, this scenario seems ripe to explore how treaty and aboriginal rights may influence a hypothetical public nuisance claim. As claimants, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation should serve notices of action to the four main oil sands operators in the area: Suncor, Canadian Natural, Syncrude, and Shell. The Alberta Energy Regulator and its predecessors should also be made defendants to the claim due to their role in approving the oil sands operation and demonstrating complicity by accepting the results of monitoring reports on the tailings ponds. In instances where a specific project was approved through a joint review by Alberta’s and the Government of Canada’s environmental assessment agencies, the Government of Canada should also receive a notice of action.

Overview of Nuisance

“The tort of nuisance … was designed to protect the plaintiff’s use and enjoyment of land.”34 Its underlying maxim holds that “one must use one’s own property so as not to injure that of one’s neighbours.”35 As I will deconstruct below, “the court must weight the plaintiff’s interest in being free from interference against the defendant’s interest in carrying on the impugned activity as well as society’s interest in allowing some types of activities. Relief is available only if, having regard to all of the circumstances, the interference was unreasonable.”36 Here, reasonableness is focused on the effect of the nuisance on the plaintiff, not the reasonableness of the defendant’s behaviour.37 This distinction means that a “defendant may be liable in nuisance, despite acting reasonably.”38

The tort of nuisance is a strategic tort for the Athabasca Chipewyans to bring since the tort is malleable in a number of ways.39 First, nuisance is capable of responding to a variety of harms since it is not limited to physical damage to property or person, but also protects “interference with the health, comfort or convenience of the owner or occupier.”40 Second, a determination of nuisance is a question of fact based on an open list of factors that judges must balance.41 This means that there is wide ambit for judicial discretion.42 Third, there are three main configurations of nuisance: (1) private nuisance, involving a single property owner claiming some form of damage; (2) public nuisance—private interests, involving a grouping of multiple private nuisance claims; and (3) public nuisance—common interests, involving a claim regarding damage to a common space or resource that is not privately possessed.43 This paper will only discuss the two manifestations of public nuisance.

Public Nuisance

Rules of procedure for different courts may require that even a small amount of individual private nuisance claims be joined at the discretion of a judge, and plaintiffs may elect to formally certify their multiple private claims as a class. Joined and class nuisance claims may intuitively resemble a public nuisance claim; however, public nuisance is its own separate group tort that “is not susceptible to any precise definition,”44 but is designed to protect the rights of the public at large.45 One major distinguishing feature of public versus private nuisance is that “a public nuisance is a nuisance which is so widespread in its range or so indiscriminate in its effect that it would not be reasonable to expect one person to take proceedings.”46 The two variations of public nuisance will be explored below, both of which borrow the substantive test from private nuisance.

Private Interests Combined

A public nuisance taking the form of combined private interests arises where a defendant’s conduct unreasonably interferes on a large scale with the use of private property.47 The seminal public nuisance case in the United Kingdom, Attorney General v PYA Quarries Ltd (No.1)48 established several principles for public nuisance which have been read into Canadian jurisprudence via Ontario (Attorney General) v Orange Productions Ltd.49 Both benches accept that the “sphere of nuisance” is often neighbourhood-wide and that it is a question of fact whether “that sphere comprises a sufficient number of persons to constitute a class of the public.”50

Lord Denning’s words imported into Canada state that “it is sufficient to show that a representative cross-section of the class has been so affected” indicating that unlike formal class proceedings, not everyone in a public nuisance claim needs to meet requirements of being “similarly affected.”51 The Ontario Court in Orange Productions clarifies that public nuisance can be established by proving “a sufficiently large collection of private nuisances.”52 Despite the lack of a numerical threshold of private nuisance claims that will allow for public nuisance, Canadian trends suggest that around ten claims leads to a public claim.53 In the hypothetical case at hand, a significant portion of the population live with fear and mental stress from the prospect of contamination. Many people have identified health effects that may be attributed to the contamination, but even if this link is not made, it is likely that a sufficient class could be made for a public claim since the mental effects of the interference are so widespread.

Common Interests

Public nuisance taking the form of common interest occurs where a “defendant’s conduct unreasonably interferes with rights, resources, or interests that are common to the entire community.”54 This subset has much overlap with the above permutation of public nuisance, but does not require occupancy of the land that is interfered with since the land is often held in commons such as rivers, forests, recreational or hunting spaces. This type of public nuisance would capture interferences felt by more of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation since it would encompass interferences with property in Treaty 8 beyond their specific reserve land. For example, entire generations currently are less able to experience their cultural traditions, and those who still partake in some aspects of traditional life are having to do so more expensively. Also, the entire community is required to spend more on food flown into Fort Chipewyan, since they have less game and fish that they feel safe eating.

Application to the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

Moving forward with assessing a public nuisance claim for the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, I would recommend that both variations of public nuisance be brought since there are elements of the claim that lend themselves to either sub-type. Some elements of the claim involving private occupancy interests include the interference with the physical and mental health of the community as well as any contamination of personal property on reserve or in Fort Chipewyan. Components that lend themselves to common interests by impacting the surrounding ecosystem in the Athabascan region include the Chipewyans’ reduced ability to hunt and fish as guaranteed by treaty, the interference with spiritual practice and custom, and the environmental damage to the waters and land.

PART III: PUBLIC NUISANCE STANDING

As I will describe below, the requirements for obtaining public nuisance standing in Canada are challenging and have potentially stymied the use of public nuisance as a tool for securing environmental protection. Public nuisance standing requires the plaintiff to either obtain consent from the Attorney General or demonstrate that they have suffered a special or particular injury that is different from the injury that the general public has experienced. It is interesting that Canadian constitutional and administrative challenges also used to employ this test for standing, but have since moved to the more deferential public interest standing test.55

Consent of the Attorney General

In Canada, the Attorney General, in their formal role as guardian of the public interest, has nearly unfettered jurisdiction regarding public nuisance “to prosecute criminally, sue civilly, or consent to [an action by an individual—also known as] a relator action.”56 This is because public nuisance is considered a quasi-penal tort, that parallels the purpose of criminal law by redressing an action that affects public interests in health, safety, and morality.57 Further policy rationales related to the Attorney General’s discretion, at least as forwarded by Australian tort scholars, are to protect the public and criminal jurisdiction of the court from civil proceedings, and to avoid multiplicity of claims.58 It should be noted that public nuisance is also an existing offence under the Criminal Code, but that the tort of public nuisance may be brought even if a criminal prosecution has not occurred.59

Public nuisance cases and other public lawsuits or relator actions are rare in Canada.60 The requirement of consent of the Attorney General is a potentially significant hurdle to bringing such a claim.61 As I will discuss in the next section, proving “special injury” is the one way in Canada that plaintiffs can avoid the requirement of permission for bringing a relator claim such as public nuisance.62

Special Injury

A private individual may bring a public nuisance relator claim without permission from the Attorney General if he or she can prove special injury. Canadian jurisprudence indicates that special injury is an injury that is “different in kind, rather than degree, from that suffered by the public at large.”63 The United Kingdom refers to this as “particular damage,” which may be a helpful way of conceptualizing the distinction between character and level of injury.64 It is worth noting that special injury is only an element of a determination of standing, and is not a component of public nuisance itself.65 Practically, this means that standing may be denied even where public nuisance exists.

Due to the relatively few and far spaced public nuisance cases in Canada, it is difficult to extract concrete or leading definitions of special injury from the jurisprudence. Despite only being heard at the trial level, the case of Hickey v Electric Reduction Co. of Canada Ltd. has persuaded subsequent courts to take a narrow view of special injury, which requires that the of special injury be different in kind not degree from what the general public suffers.66 Although, twenty years later in Gagnier v Canadian Forest Products Ltd another trial level decision over a similar situation widened the ambit of special damage indicating that “all that should need to be proved is a significant difference in degree of damage between the plaintiff and members of the public generally.”67 The court drew support for widening this understanding from three older Ontario Court of Appeal cases68 that more closely reflect the United Kingdom’s conception of special damage as damage that is “appreciably greater in degree than any suffered by the general public.”69 Gagnier thus creates ambit for courts to find special injury where there is difference in kind of injury as well as difference in degree of injury.

Special Considerations for Indigenous Communities

Facially, public nuisance is a natural tort to bring for pollution due to its emphasis on public rights, of which the common law has already recognized the public rights to clean air and water.70 Further, for Indigenous litigants specifically, the tort of public nuisance may be a more expeditious and less political route for an Indigenous community to enforce treaty or constitutional rights and offer a greater range of remedies rather than through a formal treaty or constitutional challenge.71 Although, to date, public nuisance cases have been uncommon and have yielded limited success for environmental plaintiffs.72 Various Indigenous communities of modern-day Canada, however, are uniquely situated to acquire standing in nuisance due to their special relationships with the Crown and with the land such that permission from the Attorney General to litigate may be inappropriate or the fracturing of their connection to the land may constitutes special injury.

Permission from the Attorney General is not Appropriate for Indigenous Claims

Indigenous people have a unique relationship with the Crown because of the Crown’s fiduciary obligations it undertook in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which has since been incorporated by reference in section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982.73 This means that the Crown must act in the best interests of Indigenous peoples when making decisions that may affect their interests.74 This requirement is grounded in the principle of the “honour of the Crown.”75

In simple terms, an Attorney General, who refuses to hear a First Nation’s concerns relating to its rights cannot be said to be acting honourably. “There is arguably an obligation on the Attorney General to allow a First Nation to use existing common law tools that might protect the First Nation's interests.”76 To otherwise refuse standing before an assessment of the claim on its merits does not fulfill the Crown’s fiduciary duty and harkens back to the repressive, and since repealed, 1927 amendments to the Indian Act that denied Indigenous people the ability to bring legal cases against the government without approval of the Attorney General.77

Aboriginal and Treaty Rights as Special Injury

Although currently untested, tort scholars argue that special injury, even under the more narrow Hickey conception of special injury, should include interference with Aboriginal and treaty rights as distinct from what the general public can experience.78 Indigenous people have occupied Canada from time immemorial and have benefited and built their culture around the landscape’s natural bounty.79 Because of this connection to the land, Indigenous people suffer a different kind of harm from a public nuisance than that suffered by non-Indigenous people.80 The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized that Indigenous “practice, culture or tradition” can be integral to Indigenous identity,81 and that the land, beyond it’s economic value, bears a distinct cultural component for Indigenous identity.82

Hawaii’s Supreme Court granted native Hawaiians standing in a land-use challenge, operating under the same test that Canada currently uses for public nuisance standing. The Court found that the land-based traditions practiced by native Hawaiians “for subsistence, cultural, and religious purposes” constituted “an interest […] clearly distinguishable from that of the general public.”83 Hawaii’s special interest requirement for standing is comparable to Canada’s conception of special injury. Of course, Indigenous people are not homogenous, and connection to land varies from First Nation to First Nation, but generally the interference with a constitutionally entrenched entitlement such as Indigenous hunting, fishing, trapping, harvesting, etc. under treaty due to pollution is a clear example of special injury.84 Where First Nations are on unceded land, that is land not dictated by a treaty, the prima facie case of special harm is less easily found.85

Application to the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

Considering the foregoing discussion on permission and special injury, proving special injury is highly likely for a First Nations group like the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation that is both (A) highly connected to the land, and (B) on land that guarantees significant land-based rights under treaty. I have argued that since a finding of special injury is likely, permission from the Attorney(s) General is not necessary. I have also argued that refusal by the Attorney General would not be appropriate because of the Crown’s special relationship with Indigenous peoples. Further, history shows that this consent has not been granted frequently.

Even when Canada had an Indigenous Attorney General federally, the former Honourable Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould released a directive indicating that civil litigation involving Indigenous peoples should be avoided such that “[a]dversarial litigation between the Crown and Indigenous peoples presents challenges for achieving reconciliation.”86 This directive is in keeping with the Supreme Court of Canada’s repeated message that other means of resolution and reconciliation are encouraged.87 This suggests that permission to bring a public nuisance action continues to be unlikely, and that litigants should put effort into proving special injury. As an alternative argument, the First Nations could argue that the Attorney General’s refusal to allow their claim of public nuisance is not in keeping the Attorney General’s role to act in their best interest.

In the case at hand, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation is spiritually connected to their reserve and treaty land. The fear of or actual contamination of their water and food has prevented them from carrying out their traditional livelihoods and spiritual rituals relating to the land that they were promised under Treaty 8 and the Constitution of Canada. The fracturing of this relationship with the land is likely to constitute a special injury.

PART IV: ASSESSING THE FACTORS

Once standing for public nuisance has been made out, the next step is to assess whether the harm constitutes a nuisance. This part of the assessment mirrors the two-step assessment for private nuisance, which is that the interference must be both substantial and unreasonable.88

Substantial Interference

Nuisance is not actionable per se and requires the interference to rise to the level of “substantial.”89 In 2013 the Supreme Court of Canada clarified that substantial means the significant interference with a plaintiff’s property or ability to use it, including “interference with the health, comfort or convenience of the owner or occupier.”90

The Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation’s claim certainly rises above this initial threshold question. At minimum, the community’s inability to exercise their treaty rights and partake in their cultural and traditional practices is a significant impact on their lives.91 The community is guaranteed the right to hunt and fish, but the community has reported finding growths and lesions on fish and meat in recent years making them no longer feel safe to carry on their traditional way of life and livelihood.92 This has impacted their customs and ability to pass on knowledge from one generation to the next. The people living in the community report high levels of stress, anxiety, and fear because they live on contaminated land that will make them ill.93

In addition to the cultural and psychological harm, the group has also experienced significant economic harm. The loss of the community’s ability to hunt and fish in their traditional areas has required the community to incur extra expenses flying food into their remote community to replace what they can no longer hunt or fish.94 This food is often processed and has lower nutritional levels than what the community has traditionally sustained themselves with from their hunts. Further, when members of the community do hunt, they now need to spend extra money on petroleum during their hunting trips since they are required to travel further away from the River for safer meat.95

Any one of these cultural, phycological, or economic impacts are substantial, and certainly together they meet the first part of the analysis. The potentially substantial physical health impact is another aspect that may further guide a prospective court to characterize the impact of upstream oil sands operators as substantially interfering with the lives of the First Nations. Depending on what the evidence on discovery indicates, the group may also be suffering increased levels of cancer and other health impacts from exposure to toxic elements from upstream refineries. The heightened rate of illness and death in the community would be a significant impact on the community.96 Although, to be clear, the case does not hinge on a finding of significant physical health impact due to the likely finding of other substantial interferences. The next part of the analysis balances several factors to assess whether this substantial interference is reasonable.97

Unreasonable Interference

As described in my overview of nuisance in Part II, the determination of reasonability in nuisance is a balancing exercise of multiple factors.98 While there is no black letter test, the Supreme Court of Canada has emphasized that the aim of this part of the assessment is to determine if it would be unreasonable for the plaintiff to suffer the interference without compensation.99 Traditional factors considered by courts at this stage include: (1) the severity of the interference, (2) the character of the locale, (3) the difficulty in lessening or avoiding the risk, (4) the utility of the defendant’s conduct, and (5) the sensitivity of the plaintiff. I will consider each of these in turn; however, this is not a closed list, and courts are encouraged to consider “all of the relevant circumstances.”100 In light of the uniqueness of Indigenous people’s relationship with the land and government, I will add a sixth relevant factor: the impact of the Athabasca Chipewyan’s rights under the Constitution of Canada.

1. Severity of the Interference

a. Nature of the Interference

As acknowledged by the Supreme Court, assessing the severity of the harm is a factor that overlaps with the substantial interference inquiry,101 but the severity of the interference may be a less stringent standard since this assessment is considered from the perspective of the plaintiff.102 As detailed above, the nature of the interference is pervasive in scope. The contamination in the water has affected the Chipewyan’s ability to fish, hunt, harvest, and drink water causing significant psychiatric, spiritual, and economic harm and likely significant harm to their physical health.

b. Duration of the Interference

I would further add that the duration of the contamination adds to the severity of the interference since the exposure to chemicals is ongoing.103 The first oil sands mine opened in 1967, but operation in the Athabasca Oil Sands did not expand much until the early 2000s. Since then, the number of operators, upgraders, and tailings ponds have grown.104 The effects of the Athabasca Oil Sands has increased over the last decade representing an increase in severity.

c. Effect of the Interference

To be successful, the plaintiff must show that the damage or harm is the effect of the alleged nuisance. Testimony on psychological, cultural, and economic impacts of the contamination are clear, and the health claims would need to be further investigated and updated since the 2009 Alberta report. Still, the link must be drawn that the contamination was caused by the Athabasca Oil Sands operations.

Little research has been published on contamination levels in the water and fish of the Athabasca River. A document accessed from the Department of Natural Resources Canada through an access to information request (See: Appendix B) indicated that “potentially harmful, mining-related organic acid contaminants in the ground water of a long established, out-of-pit tailings pond” was detected, but that concentrations decreased with distance from the mine.105 Some organic acids can increase the solubility of heavy metals in tailings ponds such as Zinc, Lead, and Cadmium.106 Cadmium has strong links to cancer.107 In 2009 oil sands mines in Canada produced almost 650 tonnes of cadmium, and similar volumes of chromium—another known human carcinogen.108

This declassified government document quotes an industry panel finding that the Athabasca flows through natural bitumen deposits making it difficult to determine the source of contamination. To counter this, the Chipewyans will have to ask the court to consider Indigenous Knowledge in testimony that the Chipewyans have existed for long before the oil sands operations and have noticed changes since the oil sands operations ramped up at the turn of the millennium. The community’s perception of change is supported by a 2014 scientific study that confirms that the Athabasca tailings ponds are polluting the groundwater and seeping into the Athabasca.109 Subsequent studies have suggested that 11 million litres of tailings leaks into the Athabasca River every day.110

The effect or cause of the Chipewyan’s psychological, spiritual and economic loss is highly likely to be linked to the tailings ponds. The First Nation is actively experiencing these harms and will not feel comfortable resuming their traditional way of life until their safety is assured. Impartial and comprehensive testing of water and food safety has not been undertaken. Limited sample studies have revealed mixed results. This leaves the First Nation to live in fear such that their mental health suffers, their ability to practice and pass on their cultural traditions is stymied, and they are forced to incur more financial costs to make up for lost and changed land-based livelihoods and means of self-sufficiency.

While the phycological, cultural, and economic harms are likely to be found, physical health and environmental harms may also be connected to the tailings ponds. Further scientific testing will need to establish these latter harms, but either way due to the other impacts, it is likely that a court will find that the Chipewyans are suffering a serious harm from the oil sands operations. This factor tips the balance towards a successful claim by the Chipewyans.

2. Character of the Locale

Traditionally this factor is used to increase the acceptability of an interference if the plaintiff lives in an industrial area.111 To claim that the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation lives in an industrial area and should expect some level of contamination would ignore the ongoing land-based practices of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nations and would be an extremely short-sighted approach. A full assessment of the locale is that the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation has lived since time immemorial in the pristine boreal forest and muskeg of what is now modern-day northern Alberta. In 1899 the British Crown relegated the First Nation to reserves along where the Athabasca River meets Lake Athabasca.112 This land remained relatively pristine until the recent massive expansion of industry that is only 200 kilometers from the reserves. Industry came to the First Nations, not the other way around.

Further, jurisprudence from the United Kingdom that has been imported into Canadian jurisprudence indicates that regardless of the character of the locale, “the addition of a fresh noise may give rise to a nuisance.”113 So, the increasing industrial presence and increasing contamination should tilt this factor to weigh in favour of the Chipewyans, perhaps even more so because of the historic character of the locale and ongoing relationship of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation to the land and waters.

3. Difficulty in Lessening or Avoiding the Risk

The oil sands operators, with the help of government funds, spend millions each year in innovating and greening the oil sands operations.114 Here we can anticipate that the companies will defer to their approved impact assessment and relevant government defendants will defer to the robustness of their assessment. This factor may be a harder battle for the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, and is difficult to speak to without access to expert testimony on the process of impact assessments and the design of tailings ponds.

However, known impacts from the tailings ponds should support one rudimentary change that does not require modern technological advancements or advanced knowledge to understand: Keep the tailings ponds away from the edge of the Athabasca River. Tailings ponds are (A) not lined, (B) only have gravel fill, and (C) are intended to drain fluid by design in order to leave solid dry waste that can be remediated.115 Because this design anticipates that tailings fluid will exit the system and seep into the groundwater at the assessment phase,116 it seems like common sense to keep tailings ponds further back from a vital body of water in case of an emergency spill, or chronic groundwater seepage as is the case here. From an aerial view on Google Maps, it appears that in most places, the tailings ponds are one kilometer away from the River, which apparently is not sufficient because of the mass daily volume of tailings runoff into the River. But it should be noted that in a few places, the ponds are under 500m from the edge of the River. Suncor’s massive Pond 7 on the east bank is 400 meters from the River, and other smaller Suncor ponds on the west bank of the River appear to be under 70 meters from the shore! The precautionary principle would suggest that such measures to prevent harm should not await further evidence of impact.117

Based on the proximity of the ponds to the River alone, it is highly likely that the companies and government agents could have lessened the risk by locating the ponds further back from the Riverbank. This factor thus tips towards the Chipewyans.

4. Utility of the Defendants’ Conduct

Upfront it should be noted that this factor indicates the “leniency of the remedy rather than liability itself.”118 This means that this factor should not prevent a finding of nuisance at law. The Supreme Court of Canada points out that the utility of the defendant’s conduct—as in their purpose—is to be assessed, not the nature or method by which it was carried out.119 In our case this means that we are assessing the purpose of the process of extracting and upgrading bitumen to be later refined into fuel.

From the 2000s to the date of this claim, and into the immediate future, our global economy continues to depend on oil for transportation of people and goods and in some cases, oil is still used for heating buildings. Even though oil sands production is the most expensive way to extract crude oil; Canada is the fourth largest producer of oil in the world, 96% of this total comes from the oil sands.120 Canada’s oil sands are a very important global utility, even though the sands have minimal local utility since the bulk of Canada’s oil sands production stays in the United States where it is refined.121

The utility value of what comes out of the Athabasca Oil Sands should not be overstated. Afterall the oil sands operators do not produce useable oil: they produce diluted bitumen, a form of heavy synthetic crude oil. The end-product of the Athabasca Oil Sands is highly valuable to the global economy, but this factor needs to be weighed in light of the actual value it brings to Albertans and Canadians. In the Canadian context, our value gained from this raw material is limited to economic and employment gain since value is added elsewhere as the diluted bitumen is transformed into a useable product and is ultimately consumed outside our borders. Further the oil sands employed more than 140 thousand workers in 2017;122 however, potentially more jobs are produced outside of Canada in the processing and end-product manufacture of various fuels and plastics. Further, even the economic benefit of the oil sands to Canada is reduced by the fact that 70% of “oil sands production is owned by foreign companies and shareholders.”123

Therefore, utility must be assessed in light of the value that diluted bitumen brings to Canada and not the utility of the fuel, plastic, or other end products that is realized by other countries further down the value chain. Still, it is likely that the utility factor would tip toward the corporate and government claimants due to the economic and employment benefits that the oil sands operations bring to Canada, but is not as strong a factor as some might think.

The utility factor is but one, non-determinative factor that must be considered in context of the total assessment.124 If severity of the harm and public utility were weighed equally “an important public purpose would always override even very significant harm,” which would offend the compensatory aims of tort law, generally. This would further offend the specific aim of nuisance: to not require a plaintiff to suffer “a disproportionate share of the cost of procuring the public benefit.”125

5. Sensitivity of the Plaintiff

Sensitivity of the plaintiff has traditionally worked against the plaintiff in this balancing exercise if the plaintiff has abnormal sensitivities such as being headache-prone or having a heightened sense of smell.126 This factor may weigh against the Chipewyan Athabasca First Nation if it is viewed that the Chipewyans are overly sensitive because of their connection to and dependence on the land. However, this approach diminishes and reduces the rich land-oriented history of Indigenous tradition to a trifling and abnormal condition. It could be argued that the identification of Indigenous practice as a sensitivity would reflect a gross inability of the justice system to remove its colonial lens in the spirit of reconciliation. Sensitivity of the plaintiff has not been considered as a factor in some cases and is not part of a “mandatory checklist,”127 so it is likely to be left out of the assessment here too.

6. Impact of the Constitution of Canada

As an additional consideration, the Chipewyans should advocate that the court consider the two-fold impact of their rights under Canada’s Constitution in order to support the significances of the interference. First the prima facie Charter or Charter-like infringements ought to put the thumb on the scale in the favour of finding nuisance. Second, the Aboriginal and treaty rights found outside of the Charter in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 should be a further influencing factor in the finding of nuisance.

a. Charter Rights as Influencing Factor

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms may impact tort liability by increasing the weight applied to different aspects of a common law claim against private individuals.128 The Charter can only directly apply to government actors129 and non-government actors that: exercise governmental functions; implement governmental programs; or exercise statutory powers by compulsion.130 It is unlikely that the oil sands operators meet the requisite level of effective government control131 necessary to bring them directly under the Charter; however, the Supreme Court of Canada has held that “the judiciary ought to apply and develop the principles of the common law in a manner consistent with the fundamental values enshrined in the Constitution.”132

It is beyond the scope of this paper to walk through a complete Charter analysis; however, prima facie, it appears that the Chipewyan’s right to “life, liberty, and security of the person” is compromised by contamination from upstream industry that was permitted to operate by the government.133 Additionally, the Chipewyans’ equality rights and freedom from discrimination has arguably been infringed by Government decision-makers that permit the level of pollution and refuse to investigate or take action on the health of the Chipewyans.134

Applied to a public nuisance claim against industry by the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, this added weight or flavour of a Charter-like infringement may influence a court’s weighing of factors for a finding of nuisance.

b. Aboriginal & Treaty Rights

Similarly, section 35 of the Constitution may influence a finding of nuisance. Section 35 textually recognizes aboriginal and treaty rights as part of Canada’s supreme law.135 Applied to the situation of the Chipewyans, the government-permitted upstream industry has interfered with the hunting and fishing rights under Treaty 8.136 There is Canadian jurisprudence supporting the recognition of treaty rights,137 even when the result of this is refusing development.138 Depending on the actions and steps that the federal and Albertan governments took in their permit process, section 35 may not have been respected. This would further support the finding of nuisance against government or industry as described above in relation to the Charter.

Balancing the Factors

To summarize, the interference is highly likely to be found to be substantial because of the Athabasca Chipewyans’ active and provable emotional, cultural, and economic harm suffered from the lack of assurance that their traditional food and water supply is safe. The First Nation’s health impacts if proven would further bolster the significance of the substantial interference. This interference is unreasonable due to many factors. First, as discussed, the emotional, cultural, and economic harm reaches a level of severity in nature, duration, and effect that tips the first factor in the unreasonable interference assessment towards the Athabasca Chipewyan, regardless of whether health impacts are proven. Second, the First Nation occupied the land many years before the operations in the Athabasca Oil Sands began, so should not be expected to endure such interferences. Again, the second factor tilts towards the First Nation. Third, the difficulty of lessening or avoiding the damage will turn on the testimony of tailings ponds experts, but is likely to also tip towards the Chipewyans because of the location of the ponds and their intended function.

Fourth, the production of diluted bitumen from the Athabasca Oil Sands produces a utility that would for the first time in this balancing assessment lean towards the corporate and government defendants, but is outweighed by the preceding three factors discussed and the next two factors in the analysis. Fifth, assessing the sensitivity of the Chipewyans is difficult to predict as there is no precedent for Indigenous sensitivity, but it would be culturally inappropriate to categorize the First Nation’s connection to and reliance on the land as sensitive. Sixth, as a final factor open to consideration, the Charter, constitutional, and treaty rights strongly steer towards the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation since the First Nation’s life, liberty, and security is prima facie placed at increased risk due to the governmental approval of the oil sands in the first place, and continued allowance. Also, the interference with the First Nation’s constitutionally entrenched treaty rights to hunt and fish places further weight on the scale for a finding of unreasonable interference by the oil sands operators and enabling government actors.

Whether or not the sixth factor regarding rights is considered directly, the totality of the factors in the balancing test weigh strongly in favour of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. It is likely that only the utility factor does not support the claim, but still can be whittled down to the local utility of diluted bitumen rather than the global importance of oil. The fact that utility is intended to influence remedy rather than the finding itself,139 it is highly likely that a court acting reasonably should find that the Oil Sands operators have substantially and unreasonably interfered with the Athabasca Chipewyan’s use and enjoyment of their treaty area.

PART V: POSSIBLE DEFENCES AND REMEDIES

Defences

Due to the nature of government assessment and approval of oil sands operations, the defence of statutory authority must be considered briefly. The defence of statutory authority is that after a finding of nuisance, the defendant may not be held liable if it was acting pursuant to a statute and that the nuisance was the “inevitable result” of following that statute.140 This means that the defendant must meet the high burden of proving that there were no safer means of operating.141

Applying this to our case we must ask: is the reduced ability to practice aboriginal and treaty rights and harm to human health and psychological wellbeing the "inevitable result" of Canadian Natural, Suncor, Shell, and Syncrude operating along the Athabasca River as permitted by Canada’s and Alberta’s impact assessment agencies? In reality, this requires gaining access to the site proposals and what was approved or mandated by the assessment agencies. These assessment documents are not readily located on the internet, but Directive 023 of the Alberta Energy Regulator anticipates seepage from these ponds.142 Although, statutory authorization does not give these companies “immunity for damage suffered by its neighbours.”143

In its first Directive on Tailings Performance Criteria, the forerunner to the Alberta Energy regulator commented that companies are not meeting their targets from their applications on how quickly their tailings ponds would be reclaimed.144 It was anticipated that most ponds would not meet these requirements in the near-term and some would not meet these requirements for over 40 years.145 This shows that the companies have not complied, or the Regulator was given false information to issue allowances on.

Further, depending what the impact assessments say about placement of the tailings ponds, it may be hard for the oil sands operators to show that they had no choice but to build the ponds so close to the River. It is likely that a court will find that the companies had some discretion on how far back from the river bank to build the ponds, but instead of thinking about saving the river bank, the companies chose to save the bank by spending less money through building shorter access roads to the ponds and running less pipe to pump water from the River into the tailings ponds. This choice to save money while creating increased risk is highly similar to the case of Ryan v City of Victoria where a railway company chose a cheaper rail type that increased risk to pedestrians. To modify the words of the affirmed trial judge: “The cost of that increased risk to others must fall on the defendant [oil companies]. It is a ‘cost of running the system.’”146

Based on this or any other findings of discretion on the behalf of the oil sands operators it is unlikely that the defence of statutory authority could apply. If the defence did apply because of a finding of no discretion then it would not be a full defence as the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that “statutory authority provides, at best, a narrow defence to nuisance.”147 Even still, if a court were to find that the companies should not be liable, this claim would hold the Albertan and Canadian governments squarely liable for their strong hand in allowing the oil sands operations.

Remedies

The most common remedies include injunctive relief and damages; however, abatement is possible.148 Judges must balance interests in determining which to award.149 Injunctions could be prohibitory or mandatory, interlocutory or permanent;150 however, due to the continuing utility of oil in the current day, as described above, an injunction of any kind on oil sands production seems highly improbable. Further, the specific problem of leaking tailings ponds cannot simply be ordered to stop leaking in absence of an engineering solution.151 Damages, possibly paired with abatement, are likely the preferred route.

In the 2004 case of British Columbia v Canadian Forest Products Ltd the court identified three potential categories of compensation for public nuisance: Loss of the (1) use, (2) existence, (3) inherent values.152 The court upheld the first two values as appropriate means of capturing damages for environmental harm. First, the use value is the cost of benefits that flow from the direct use of the environment including harvesting, fishing, hunting, and enjoyment of recreational activities.153 Second, the passive or existential value of the environment is the benefit gained from indirect use of the land and includes the cost of saving the ecosystem for future generations’ direct use.154 In our case experts in environmental valuation would need to calculate the environmental damage in a culturally appropriate way that captures the loss of Indigenous land-based traditions and customs.

In addition to environmental valuation of damages, the impact of reduced mental and physical health would need to be determined. Courts are more familiar with this kind of damage calculation, but would again have to do so in a culturally sensitive way that takes into account the highly communal perspective of the Athabasca Chipewyans.

Damages could be shared by the governments and companies. The Alberta Government was primarily in charge of the approval of its local operations like the tailings ponds so would take larger if not complete responsibility compared to the federal government.155 As for companies, Suncor has been onsite for the longest, has the largest operations, and has ponds closest to the River, so would absorb a large amount of the liability that is assigned to the companies. Following Suncor, in decreasing order of liability based on scale and proximity to the River as perceived from an aerial view, Canadian Natural, Syncrude, and lastly, Shell would be liable. This order of liability may change if found that one company’s tailings pond walls were particularly permeable.

In addition, the possibility of a remedy such as environmental abatement may be available; however, courts are reticent to impose specific performance where oversight is required. However, environmental abatement of the area, if possible, would be ideal for the Chipewyans, and this may arise through regulatory action following a successful civil claim or even voluntary action by the defendants to avoid future damages. Creative recovery packages for the community such as school, training, and nutrition programs paid for by the defendants may be another option under the self-help remedy.

CONCLUSION

Public nuisance is a hopeful area for protecting the land-based rights of Indigenous people under treaty from pollution.156 As discussed, permission from the Attorney General to bring a relator claim may be antiquated in itself, and may also be an inappropriate requirement for Indigenous claimants due to the conflict it creates between the Attorney General’s duties to act in the interest of the First Nations and to exercise jurisdiction over quasi-penal torts. The special spiritual and legal relationship of Indigenous people in Canada with the land through culture and treaty is likely to be categorized as a special harm if interfered with. A finding of special harm would allow a group to proceed to litigation without permission from the Attorney General.

Once past the question of standing, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation is likely to find success in this case since a balancing of all factors demonstrates that the impact that they are suffering from the fear of or actual contamination from the Athabasca Oil Sands operations is both substantial and unreasonable. The impact on their mental, cultural, and economic wellbeing is severe as is the likely impact on their physical health. The First Nation should not be made to suffer the expansion and corresponding increased contamination from a relatively recent interference to their long occupancy of the locale. This interference is particularly unacceptable considering that the interference could have been avoided through better management of the by-products of bitumen and better design of the tailings ponds to limit seepage near groundwater and the River. Further the First Nation is not sensitive in the way that this factor has traditionally been understood and I argue that it would be erroneous to categorize them as such. Finally, the Athabasca Chipewyan’s claim is strengthened by their constitutional rights that make this interference more unreasonable.

Taken together it is likely that a court acting reasonably would find that the Athabasca Chipewyans’ enjoyment of their traditional lands has been substantially and unreasonably interfered with. This finding could not be entirely mitigated by the defence of statutory authority, since it is likely that the companies had more breadth of discretion to increase the safety of the storage of tailings. Also, the fact that the companies have not met all performance criteria for tailings management shows that they were not acting entirely pursuant to their approval plans or subsequent directives. This suggests that a remedy is likely and should not be significantly reduced by the utility of bitumen in the Canadian context.

An award could help the community adjust to their altered way of life and recover some of their traditions. A successful finding of nuisance could also make it easier for future Indigenous communities affected by industrial contamination to recover their losses. Moving forward, an award would also motivate governments and industry actors to improve their practices to prevent future harm to Indigenous peoples living in close proximity to contaminated sites as noted by the United Nations Special Rapporteur.

Cancer sites with a statistically significant increase in the number of observed incidence cases in Fort Chipewyan, 1995-2006, comparing findings from the 99%CIs, 95%CIs and 90%CIs of ISIRs and the simulation.

See chart from Alberta Cancer Board's report, "Cancer Incidence in Fort Chipewyan, Alberta 1995-2006", at page 85.

Appendix B

See Memo to Minister of Natural Resources Canada, accessed through access to information request.

Endnotes

3 Lynda Collins & Heather McLeod-Kilmurray,

The Canadian Law of Toxic Torts, (Toronto, Ont: Thomas Reuters, 2014 at 55, 217 [

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray]

4 “

History” (last accessed 15 March 2020), online: Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation.

6 Ibid; Treaty No 8 Made June 21, 1899, online: Treaty 8 Tribal Association, [

Treaty 8] at 2.

7 Treaty 8,

supra note 6 at 1.

10 “Canadian History Workshop” (January 2013), online:

Word Press .

14 “

What are oil Sands?” (last accessed 20 March 2020), online: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers; Erin Kelly et al, “Oil Sands Development Contributes Elements Toxic at Low Concentrations to the Athabasca River and its Tributaries” (2010) 107:37

Proceedings National Academy of Sciences 16178.

15 “

What are oil Sands?” (last accessed 20 March 2020), online: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers; Erin Kelly et al, “Oil Sands Development Contributes Elements Toxic at Low Concentrations to the Athabasca River and its Tributaries” (2010) 107:37

Proceedings National Academy of Sciences 16178.

16 Government of Canada, “Oil Sands: Tailings Management” online (pdf): at 1

Natural Resources Canada [

Tailings Management].

17 “Directive 074: Tailings Performance Criteria and Requirements for Oil Sands Mining Schemes”, (3 February 2009) online:

Alberta Legislative Assembly [

Directive 074]; “Directive 085: Fluid Tailings Management for Oil Sands Mining Projects”, (12 October 2017) online:Alberta Energy Regulator [

Directive 085].

18 Directive 023: Oil Sands Project Applications”, (28 May 2013) online:

Alberta Energy Regulator at sections 8.3.3(2), 8.6(7) [

Directive 023].

19 Tailings Management, supra note 16 at 1.

21 Alberta Cancer Board,

supra note 11 at 63.

25 Alberta Cancer Board,

supra note 11 at 6.

27 Types of cancers that were elevated in the community, but fell below statistical significance include: digestive system cancers, including esophageal cancer; cholangiocarcinoma and other sub-categories of biliary tract cancer; liver cancer; colorectal cancers including, colon, rectum and rectosigmoid junction cancers; lung cancer; kidney cancer; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; endometrium cancer; brain cancer; and cancer so progressed that the origin organ cannot be determined.

Ibid.

28 Sté phane M. McLachlan & Clayton H Riddell, “Environmental and Human Health Implications of Athabasca Oil Sands” (7 July 2014), online (pdf):

Land Use Alberta, at 138.

34 Robert Solomon et al,

Cases and Materials on the law of Torts, 7th ed (Toronto, ON: Thomas Reuters, 2015) at 909.

35 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray, supra note 3 at 56;

Oxford reference online: sub verbo “sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedas”.

36 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 909.

38 Beaty v Waterloo (Regional Municipality), 2011 ONSC 3599.

40 Antrim Truck Centre Ltd v Ontario (Transportation), 2013 SCC 13 at para 23 [Antrim];

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 56.

41 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 909;

Ryan v Victoria (City), [1999] 1 SCR 201 at para 53, 168 DLR (4th) 513; CED (Ont 4th), vol 1, title 2 (c) at §11.

42 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 909.

43 Ibid at 910, 935;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 52, 56.

44 John Murphy,

Street on Torts, 12 ed (New York: Oxford, 2007) at 457.

45 Gage,

supra note 39 at 40.

46 Ibid at 461;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 35 at 52,

Ontario (Attorney General) v Orange Productions Ltd, [1971] OR 585 at para 10, 21 DLR (3d) 257 [Orange Productions] (citing and incorporating UK case,

PYA Quarries);

Attorney General v PYA Quarries Ltd (No.1), [1957] 2 QB 169, 1 All ER 894 (UK) [PYA Quarries]

47 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 935.

48 PYA Quarries,

supra note 44.

49 Orange Productions,

supra note 44.

53 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 935.

55 Gage,

supra note 39 at 50-52.

56 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 936;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 32, 53;

Gage,

supra note 39 at 48.

57 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3at 52;

Gage,

supra note 39 at 40, 47-48;

Reference as to the Validity of Section 5a of the Dairy Industry Act, [1949] SCR 1 at 50, 1 DLR 433.

58 J. Fleming, The Law of Torts, 7th ed. (Melbourne: Law Book Company Limited, 1987) at 380.

59 Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46 s 180(2),

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 53;

Solomon,

supra note 34 at 935-36;

Murphy,

supra note 44 at 458.

60 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 53.

61 Gage,

supra note 39 at 40, 49.

62 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 936;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 53.

63 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 53.

64 Murphy,

supra note 44 at 458.

65 Gage,

supra note 39 at 59.

66 (1971), 21 DLR (3d) 368, 2 Nfld & PEIR 246 [Hickey].

67 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 43, 54; [1990] 51 B.C.L.R. (2d) 218, 23 A.C.W.S. (3d) 1040 at 43 [

Gagnier].

68 Ibid; citing

Crandell v Mooney (1878), 23 UCCP 212;

Rainy River Navigation Co v Ont & Minnesota Power Co (1914), 26 OWR 752, 6 OWN 533, 17 DLR 850; and

Rainy River Navigation Co v Watrous Island Boom Co (1914), 26 OWR 456, 6 OWN 537.

69 Murphy,

supra note 44 at 459; citing

Walsh v Ervin [1952] VLR 361;

Boyd v Great Norther Rly Co [1895] 2 IR 555 (UK).

70 Gage,

supra note 39 at 42.

71 Ibid at 43-47; Lynda Collins, “Protecting Aboriginal Environments: A Tort Law Approach” in Sandra Rodgers, Rakhi Ruparelia & Louise Bé langer-Hardy, eds., Critical Torts (Toronto: Lexis, 2008) at 67-70.

73 Ryan Beaton, “

The Crown Fiduciary Duty at the Supreme Court of Canada: Reaching Across Nations, or Held Within the Grip of the Crown” (January 2018), online (pdf):

Centre for international Governance Innovation at 1-5;

Guerin v The Queen, [1984] 2 SCR 335 at 336, 13 DLR (4th) 321,

Gage,

supra note 39 at 53-54;

Royal Proclamation, 1763, RSC, 1985, App II, No. 1;

Constitution Act, 1982, ss 35, 52(1), being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

74 Gage,

supra note 39 at 53-54.

75 Ibid;

Haida Nation v British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 SCC 73 at paras 16-25.

76 Gage,

supra note 39 at 55-56.

78 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 54-55;

Gage,

supra note 39 at 55-56.

79 Gage,

supra note 39 at 52.

80 Collins,

supra note 71 at 61;

Gage,

supra note 39 at 57.

81 R v Van der Peet, [1996] 2 SCR 507 at 549, 137 DLR (4th) 289.

82 Delgamuukw v British Columbia, [1997] 3 SCR 1010 at 1089-90, 153 DLR (4th) 193.

83 Public Access Shoreline Hawaii v Hawaii County Planning Commission, 903 P 2d 1246 (1995) at 1255-56 cited in

Gage,

supra note 39 at 57.

84 Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 54-55;

Gage,

supra note 39 at 58-59.

85 Gage,

supra note 39 at 59-61,

Collins,

supra note 80 at 71.

88 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 19.

89 Ibid; Solomon,

supra note 34 at 908.

90 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 23.

91 Treaty 8,

supra note 6.

92 McLachlan & Riddell, supra note 28;

Garibaldi, supra note 31.

93 McLachlan & Riddell, supra note 28;

Garibaldi, supra note 31.

94 Garibaldi, supra note 31 at 45-49, 54-55.

96 Alberta Cancer Board, supra note 11.

97 Solomon,

supra note 34 at 909;

Ryan v Victoria (City), [1999] 1 SCR 201 at para 53, 168 DLR (4th) 513.

98 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 25;

Solomon,

supra note 34 at 909;

Ryan, supra note 41 at para 53.

99 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 25.

100 340909 Ontario Ltd v Huron Steel Products (Windsor) Ltd, 1990 1 ACWS (3d) 1242 at para 14 73 OR (2d) 641 [Huron Steel];

Antrim,

supra note 40 at paras 25-26.

101 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 20.

102 Huron Steel,

supra note 100 at para 16.

103 Huron Steel,

supra note 100 at paras 51-53;

Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 26.

104 “

History” (last accessed 28 March 2020), online: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

105 Declassified Memorandum to Minister re: Oil Sands region of the Athabasca River, Alberta (9 June 2012).

106 Suzette Burckhard, Paul Schwab & Katherine Banks, “The Effects of Organic Acids on The Leaching Of Heavy Metals From Mine Tailings” 1995 41:2-3

Journal of Hazardous Materials 135.

107 “

Cadmium” (last accessed 20 March 2020) online: World Health Organization.

109 Richard Frank et al, “Profiling Oil Sands Mixtures from Industrial Developments and Natural Groundwaters for Source Identification” 2014 48:5

Environmental Science & Technology 2660.

111 Murphy,

supra note 44 at 437.

112 Treaty 8,

supra note 6.

113 Rushmer v Polsue & Alfieri Ltd, [1907] AC 121; 3 WLUK 32 in

Huron Steel,

supra note 100 at para 74.

116 Directive 023,

supra note 18 at ss 8.3.3(2), 8.6(7).

118 Huron Steel,

supra note 100 at para 75;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 215.

119 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 28.

124 Antrim,

supra note 40 at para 30, 38;

Tock v St. John's (City) Metropolitan Area Board, [1989] 2 SCR 1181 at 1226, 64 DLR (4th) 620.

125 Tock, supra note 124.

126 Murphy,

supra note 44 at 438-39.

127 Ryan supra note 41;

Antrim,

supra note 40.

128 Solomon,

supra note 41 at 864, 866.

129 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 32(1)(a), Part I of the

Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11 [

Charter].

130 Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority v Canadian Federation of Students—British Columbia Component, 2009 SCC 31, at para 15-16.

132 RWDSU v Dolphin Delivery Ltd, [1986] 2 SCR 573 at para 39, 33 DLR (4th) 174.

133 Charter, supra note 129 at s 7.

135 Constitution Act, 1982, ss 35, 52(1), being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

136 Treaty 8, supra note 6.

137 R v Marshall [1999] 3 SCR 456 (Aboriginal treaty rights now impose a restraint on the government’s exercise of power);

Mikisew Cree v Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage), 2005 SCC 69 (Governments have a power to exercise their treaty rights subject to consultation with Indigenous peoples where the exercise of those treaty rights would have an adverse effect on Aboriginal treaty rights);

Grassy Narrows First Nation v Ontario (Natural Resources), 2014 SCC 48 (Treaty made by the Crown therefore requiring provincial and federal governments to respect treaty rights and consult with First Nations where treaty rights are negatively implicated).

138 Saanichton Marina Ltd v Claxton, [1989] 57 DLR (4th), 161 36 BCLR (2d) 79 (Marina development permit refused due to impact on First nations group to continue their traditional fishing and harvesting under treaty).

139 Huron Steel,

supra note 100 at para 75;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 215.

140 Ryan supra note 41 at para 53.

141 Tock v St. John's (City) Metropolitan Area Board, [1989] 2 SCR 1181 at 1226, 64 DLR (4th) 620 in

Ryan supra note 41 at para 55;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 217.

142 Directive 023,

supra note 18 at ss 8.3.3(2), 8.6(7).

143 St Lawrence Cement Inc. v Barrette, 2008 SCC 64 at para 12, 89.

146 Ryan supra note 41 at para 53.

148 Solomon,

supra note 41 at 942.

152 2004 SCC 38 at para 116 in Stewart Elgie & Anastasia M Lintner, "The Supreme Court's Canfor Decision: Losing the Battle but Winning the War for Environmental Damages" (2005) 38:1 UBC L Rev 223 at 250.

153 Elgie & Lintner, supra note 152 at 251.

155 Economic Contributions, supra note 114.

156 Lynda M Collins & Meghan Murtha, "Indigenous Environmental Rights in Canada: The Right to Conservation Implicit in Treaty and Aboriginal Rights to Hunt, Fish and Trap" (2010) 47:4 Alta L Rev 959 at 964;

Collins & McLeod-Kilmurray,

supra note 3 at 54