Specific details regarding the decision to issue a No Action Letter (NAL) in relation to PayPal Inc.’s (PayPal) acquisition of HWLT Holdings (Hyperwallet) are protected by section 29 of the Competition Act and therefore will not be discussed in this article.

Multi-sided markets are a hot topic in antitrust following the United States Supreme Court’s (SCOTUS) American Express (AMEX) decision. In Canada, similar issues were previously examined by the Competition Tribunal (Tribunal) in the Commissioner’s application under section 76 of the Competition Act against Visa and MasterCard (Credit Cards). Looking back, it is understandable that the Credit Cards decision may not be front of mind since it feels like 2012-2013 was so long ago. It was a time when Stephen Harper was still Prime Minister and Gangnam Style became the first YouTube video to reach one billion views. For the Competition Bureau (Bureau), however, that decision remains front of mind when assessing multi-sided markets.

Recently, the Bureau reviewed a merger involving multi-sided platforms. In this article, we will compare the Tribunal’s guidance to that of SCOTUS in the AMEX case. We will describe why mergers involving multi-sided platforms may be more effectively examined by focusing on effects rather than strictly defining relevant markets.

Background

As technology and innovation continue to change the economy, the Bureau and the Bar must be cognizant of what impact these changes may have on antitrust analysis. Analyzing mergers and conduct in dynamic markets that are subject to continuous change can add complexity for the Bureau and other foreign antitrust authorities. Proper enforcement must strike the right balance between taking steps to prevent behaviour that truly harms competition and avoiding over-enforcement or delays that could chill innovation and dynamic competition.

To that end, the Bureau strives to keep pace with how technology is changing the way firms compete and how consumers purchase goods and services. It is tough to find a recent speech delivered by the previous or current Commissioner of Competition that does not discuss how technology has changed how we approach reviews.

The Bureau has also produced two in-depth papers discussing issues related to technology and innovation. In 2017, the Bureau published its market study on Technology-Led Innovation in the Canadian Financial Services Sector (the FinTech Paper)Footnote1. The Fintech Paper made 30 recommendations to Canada's regulators and policy makers, 11 of which focused on how to strike the right balance in regulation to ensure Canadians are protected while promoting innovation.

The Bureau also published a white paper entitled Big Data and Innovation: Implications for Competition Policy in Canada (the Big Data Paper)Footnote2. Our Big Data Paper addressed the critical importance of data, and whether the Bureau’s analytical framework continues to be well equipped in cases involving big data.

Part and parcel with the discussion of big data and dynamic markets is a discussion of multi-sided platforms. Many e-commerce platforms or markets are often thought of as two-sided or multi-sided platforms.

Multi-sided platforms have been discussed in cases before the Tribunal and courts abroad; however, these decisions are not unequivocal on the correct approach to assessing a multi-sided platform. The Bureau considered these issues in a recent case involving PayPal’s acquisition of Hyperwallet, which closed in November 2018 (the PayPal Transaction).

But what is a Multi-Sided Platform?

There are many ways to define a multi-sided platform. According to an OECD study, a multi-sided platform can be considered an intermediary economic platform having two or more distinct user groups that provide each other with network benefitsFootnote3. With this can come an “indirect network effect”, in which the value of the platform to one group depends on the membership of the second group. If one side attracts more users, it makes the membership on the other side more valuable which can lead the other side to also attract more users, and so on.

An “old economy” example of a multi-sided platform is the yellow pages. The yellow pages provide a product to both advertisers and readers. An increase in the number of contractors advertising in the yellow pages will enhance the yellow pages’ value to consumers looking for a product or service. Similarly, an increase in the number of yellow pages readers will increase a prospective advertiser’s value of advertising in the yellow pages. New developments in technology have brought about new multi-sided platforms, such as ride sharing platforms. The more drivers and riders there are on a particular platform, the more valuable that platform becomes.

What do the Courts say about all this?

In Canada, we saw a multi-sided platform case before the Tribunal in Credit Cards. In that case, the Tribunal accepted the Bureau’s position on market definition. The Bureau argued that each side of the credit card market can be considered a distinct relevant product market as long as the cross-platform interdependence is accounted for, and the Tribunal found as follows:

[O]ne side of the platform can be a candidate relevant product market for the purposes of the hypothetical monopolist test and … the SSNIP can be applied to the price charged to customers on that side of the platform provided both the interdependence of demand, feedback effects and ultimately changes in profit on both sides of the platform are taken into accountFootnote4.

The conduct at issue in the AMEX case was anti-steering practices in contracts with merchants who accept AMEX as a payment method. The plaintiffs claimed that each side of a credit card transaction, the cardholder on one side and the merchant on the other, is a distinct product market. Similar to the Tribunal, the SCOTUS decision stated that “competition cannot be accurately assessed by looking at only one side of the platform in isolationFootnote5.” However, it was not clear whether the SCOTUS decision was more limited in scope than that of the Tribunal. SCOTUS appeared to draw distinctions between multi-sided platforms and “transaction platforms” which were described as a subset of multi-sided platforms that “cannot make a sale to one side of the platform without simultaneously making a sale to the other” [emphasis added]Footnote6. The SCOTUS approach was described as follows:

In this case, both sides of the two-sided credit-card market—cardholders and merchants—must be considered. Only a company with both cardholders and merchants willing to use its network could sell transactions and compete in the credit-card market. And because credit-card networks cannot make a sale unless both sides of the platform simultaneously agree to use their services, they exhibit more pronounced indirect network effects and interconnected pricing and demand. Indeed, credit-card networks are best understood as supplying only one product—the transaction—that is jointly consumed by a cardholder and a merchant. Accordingly, the two-sided market for credit-card transactions should be analyzed as a wholeFootnote7.

It appears that one of the main differences could be that the Canadian decision applies to a broader range of industries than the SCOTUS decision.

Do I have to Define a Product Market?

As antitrust practitioners, we have all been part of vigorous debates over product and geographic markets. The SSNIP test – a concept so engrained in antitrust that this publication bears its name – involves measuring changes in the consumption of a product in response to a small but significant non-transitory change in price.

However, as noted in Section 3.1 of the Merger Enforcement Guidelines, market definition is not critical to determining if a transaction is anti-competitive:

In determining whether a merger is likely to create, maintain or enhance market power, the Bureau must examine the competitive effects of the merger. This exercise generally involves defining the relevant markets and assessing the competitive effects of the merger in those markets. Market definition is not necessarily the initial step, or a required step, but generally is undertakenFootnote8.

The Big Data Paper acknowledged that platform markets may be one such circumstance where the Bureau may appropriately place more emphasis on analyzing effects rather than strictly defining markets:

[I]f a newspaper gains the ability to raise advertising rates only because it has increased its circulation by dropping the price to readers, such a price increase to advertisers may not result in extra profits and so may not reflect an increase in market power. In that sense, it differs from a price increase by a non-platform firm, which, all else equal, will result in extra profits.

Platforms generally earn profits that are a function of the multiple prices they choose. Thus, exclusive focus on one price chosen by a platform can miss critical elements of the platform’s business realityFootnote9.

Market definition is ultimately an analytical tool to assist in evaluating competitive effects. In certain cases involving a platform, where strictly defining markets is of less probative value, it may be more appropriate to focus on direct evidence of competitive effects. This was the Bureau’s approach in the PayPal transaction, which involved the analysis of a platform.

How did the Bureau Approach Multi-Sided Platforms in the PayPal Transaction?

In 2018, the Bureau reviewed the PayPal Transaction to determine whether there could be anti-competitive effects from PayPal’s proposed acquisition of Hyperwallet. While PayPal operates many business units, the Bureau’s review focused on PayPal’s E-Wallet, its digital payment platform that provides a user with the ability to make and receive payments. Hyperwallet operates accounts payable software that facilitates mass payouts.

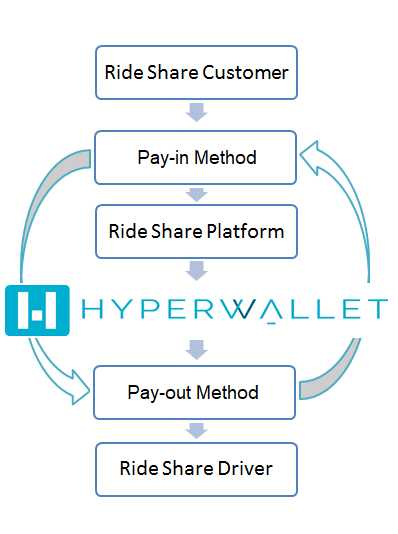

PayPal’s E-Wallet can be considered a multi-sided platformFootnote10. PayPal serves as: (1) payment method on the ‘pay-in’ side of a transaction where someone is paying for an item through their PayPal E-Wallet, and (2) the ‘pay-out’ side where someone is receiving funds that are being paid out to them into their PayPal E-Wallet. Put more simply, sending money means pay-in, and receiving money means pay-out. Often, in between the pay-in and the pay-out is the digital marketplace or e-commerce retailer, which acts as a middleman or facilitator of the exchange of goods and services for money.

Hyperwallet, on the other hand, operates an accounts payable software that assists marketplaces or retailers with making large quantities of pay-outs.

Using a simplified example of a ride sharing application, a ride share user can order and pay the ride share platform for a ride via a handful of payment methods such as Visa, MasterCard, or PayPal’s E-Wallet (pay-in). Hyperwallet, on behalf of the ride share platform, would then process payment to the drivers. Drivers can then choose to be paid via a handful of methods such as directly into a bank account, to a debit card or prepaid card, or into a PayPal E-Wallet (pay-out).

Using a simplified example of a ride sharing application, a ride share user can order and pay the ride share platform for a ride via a handful of payment methods such as Visa, MasterCard, or PayPal’s E-Wallet (pay-in). Hyperwallet, on behalf of the ride share platform, would then process payment to the drivers. Drivers can then choose to be paid via a handful of methods such as directly into a bank account, to a debit card or prepaid card, or into a PayPal E-Wallet (pay-out).

The Bureau’s theory of harm was a vertical theory: would the PayPal Transaction create an incentive for PayPal to foreclose access to its PayPal E-Wallet as a payment method to Hyperwallet’s rivals post-transaction? We were therefore focused on the pay-out portion of the transaction.

However, one key factor the Bureau assessed was the level of cross-platform interdependence. That meant assessing the “feedback effects” between the pay-in and pay-out sides of the PayPal E-Wallet. The Bureau considered how changes on one side of the transaction affect demand on the other side of the platform. When estimating effects on competition from the PayPal Transaction, the Bureau focused on the pay-out side, but included estimates of the ”multiplier” from its interdependence on the pay-in side.

Put simply, PayPal could theoretically decide a price increase for pay-out customers was profitable if it only considered the quantity effect of the pay-out side of the platform. However, if PayPal considers that a lost pay-out customer may result in a lost pay-in customer (and so on), PayPal may no longer find a price increase to be profitable.

It is unclear whether, if one were to apply the SCOTUS methodology to a review of the PayPal Transaction, it would result in a different conclusion. This platform, however, is not necessarily a “transaction platform” involving simultaneous transactions. Consistent with the guidance from the Tribunal, the Bureau examined the feedback effects on the two sides of the platform; however, this was not in the context of an assessment of product market. Interestingly, in this case it was not necessary to come to a definitive conclusion on the bounds of the product market. Instead, it was more appropriate to incorporate an analysis of the level of cross-platform interdependence into the assessment of competitive effects.

It should be noted that, while this was an interesting and relevant topic during this review, it was not the determinative issue as to why the Bureau issued a NAL. There were several other mitigating factors that led to the Bureau’s conclusion on this matter. In the context of effects on a platform, the Bureau was able to assess the effects of the merger without strictly defining the relevant markets. Cross-platform interdependence, and the feedback effects from other sides of the platform, made market definition a less probative exercise in its review of the PayPal Transaction.