Note: This article was previously published in the April 24, 2017, CBA-BC Business Law Quarterly. It is republished with permission. This article was adapted from a chapter of Transparency International Canada’s December 2016 report “No Reason to Hide: Unmasking the Anonymous Owners of Canadian Companies and Trusts.”

Canada is fast becoming a destination of choice for money launderers worldwide, who are taking advantage of our under-regulated, loophole-riddled property market to wash and hide billions in illicit wealth. Canada is both a desirable place to live and an attractive market in which to invest. But those looking to launder money or evade tax are equally attracted to our opaque ownership rules, our low levels of compliance with anti-money laundering (AML) regulations,1 and limited AML enforcement. We need to do more to deter this type of investment.

In September 2016 the world’s AML standard-setter, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), published an assessment of Canada’s performance that found the Canadian real estate sector to be “highly vulnerable to money laundering.”2The federal government reached a similar conclusion during a risk assessment completed in 2015.3 According to the FATF report, the real estate market “is exposed to high risk clients, including [politically exposed persons], notably from Asia.” The FATF report refers to “cases of Chinese officials laundering the [proceeds of crime] through the real estate sector, particularly in Vancouver.”4 The Chinese government has identified Canada as a high priority market for recovering assets bought with stolen public funds.5

Three factors make Canadian real estate particularly attractive for money laundering: First, Canadian land title offices do not hold information about beneficial owners of property, effectively granting them anonymity. Second, though the bar for AML compliance is set lower for real estate professionals than it is for most other reporting entities and individuals, the industry is still notoriously poor at fulfilling its duties under Canada’s AML laws. And third, the enforcement of those AML laws is so lax that there is little deterrent for those looking to launder money through Canadian property. These three issues are discussed in the following pages. The article then concludes with a case study examining the prevalence of opaque ownership structures in Vancouver’s luxury residential property market.

Opaque ownership

Those looking to conceal their beneficial ownership of property typically avail themselves of one or more of the following tools: holding companies, nominees and trusts.

Nominees

Headlines were made in May 2016 when a student from China bought a Vancouver mansion for $31.1 million.6 Though the value of the transaction was unique, the deal reflects a wider trend whereby unemployed individuals are acquiring luxury property in the city with other people’s capital. A 2015 study looked at a sample of 172 Vancouver homes purchased in the last several years for $1.25 million to $9.1 million, and found that 35 per cent of them were owned by either homemakers or students.7 Research by Transparency International Canada found that 11 of Greater Vancouver’s 100 most valuable residential properties are owned on paper by students or homemakers. These individuals have no clear source of employment income and are likely nominees for family or friends, though in the absence of more comprehensive public data we cannot know for certain.

The use of nominee owners is a common tool for money laundering through real estate. A 2004 study of 149 Proceeds of Crime cases successfully pursued by the RCMP found that nominee owners were used in over 60 per cent of real estate purchases made with laundered funds.8

Beneficial owners can use nominees to avoid or evade tax by claiming principal residence or first-time homebuyer exemptions.9 Recent investigations show that in some cases the principal residence exemption is being used to defraud the tax authorities on a commercial scale. In September 2016, The Globe and Mail reported on the activities of a Vancouver-based businessman, Kenny Gu, who had bought and sold dozens of properties financed by Chinese investors.10 Though Gu was the beneficial owner and had absolute control of those properties, his investors’ names were used to hold title and secure mortgages. According to documents reviewed by the newspaper, many of the properties were listed as principal residences for Gu’s clients despite the fact that they did not live in the homes. Principal residences have distinct tax benefits: taxpayers are not required to report the sale of a principal residence and they receive an exemption from capital gains tax. Contracts show that Gu’s investors would receive a set return of around 15 per cent, while he pocketed any remaining profit. Neither Gu nor his clients appear to have paid tax on their gains.

Holding companies

In Canada, as in many other jurisdictions, legal entities can hold title to properties. Special purpose companies are useful and legitimate tools in commercial real estate, where joint ventures are common and developers need to limit liability to a single project. More controversially, those buying and selling commercial properties can also avoid property transfer tax by selling equity in a holding company rather than changing the titleholder.

For the time being, this tax loophole is also available to owners of residential property that is held through legal entities.11 Beneficial owners can use holding companies to keep their identities secret, making their use appealing to people with something to hide.

Companies are used extensively to hold luxury property in international hubs such as London and New York. A February 2015 investigative report by Transparency International UK revealed that more than 36,000 London properties are held by companies registered in offshore havens such as the BVI, Jersey and the Isle of Man. More than 75 percent of properties investigated by the London Metropolitan Police as suspected proceeds of corruption are held through offshore companies.12 A New York Times investigation, also from February 2015, showed how more than 200 shell companies owned apartments in Manhattan’s iconic Time Warner Center.13 Many of those apartments were traced back to politically exposed persons and controversial international business figures. According to that article, more than half of the luxury properties sold in New York City in 2014 were bought through shell companies.

Using companies to create a veil between beneficial owners and their properties is more common in Canada than one might expect. Transparency International Canada’s research shows that nearly one-third of the 100 most valuable residential properties in Greater Vancouver are owned through holding companies. Most of those companies are registered in Canada, so the identities of their directors and officers are a matter of public record, but their ownership is not. Several companies are registered in offshore jurisdictions where nothing but the most basic information is disclosed.

Trusts

Property in Canada can be owned through trusts, the existence of which may or may not be disclosed on title documents. Canadian properties may be held through bare trusts, which separate the legal title from beneficial ownership but give the trustees no decision-making powers. According to some lawyers, bare trusts have become a common tool to avoid paying property transfer tax in some provinces, in particular in BC where tax is only payable when a change in legal title is filed with the land title office.14 It is impossible to know how many properties are held through these arrangements, as they are not registered and do not appear on land title records.

Compliance

Gatekeepers and intermediaries such as brokers, developers, notaries and lawyers are involved in the vast majority of real estate transactions and therefore can play a key role in detecting money laundering. Most of these gatekeepers have obligations under Canada’s AML law (the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA)) and its regulations. However, data from the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) shows that there are dismal levels of AML compliance among professionals in the real estate sector.15 Since a February 2015 Supreme Court ruling, PCMLTFA obligations no longer extend to lawyers and Quebec notaries, and several other types of intermediaries in the real estate sector – such as mortgage brokers and private lenders – are not covered by the current legislation.

Canada is one of a handful of G20 countries where real estate agents are not required to identify the beneficial owners of clients buying and selling property.16 Some 20,000 Canadian real estate brokers are covered by the PCMLTFA, but there are major shortcomings in their compliance with the Act.17 A recent review by FINTRAC of some 800 agencies found “significant” or “very significant” deficiencies at 60 per cent of them with respect to money laundering controls.18 According to FINTRAC, in the decade from 2003 to 2013, only 279 suspicious transaction reports were filed in relation to real estate transactions, despite some five million sales taking place.19

Enforcement

It seems that little is being done to push real estate professionals to take their responsibilities more seriously. Despite pervasive non-compliance with Canada’s anti-money laundering law, FINTRAC has only issued 12 financial penalties against realtors since December 2008.20 All of those penalties have been in the thousands or tens of thousands of dollars, which is less than a realtor’s commission on most property deals. Though there are criminal penalties of up to $2 million and five years’ imprisonment for failure to report suspicious transactions, no known cases against real estate professionals have been pursued.21 In its September 2015 evaluation of Canada’s AML efforts, the FATF found that our sanctions were too low and too rarely enforced to be an effective deterrent.

Case study: Vancouver luxury real estate

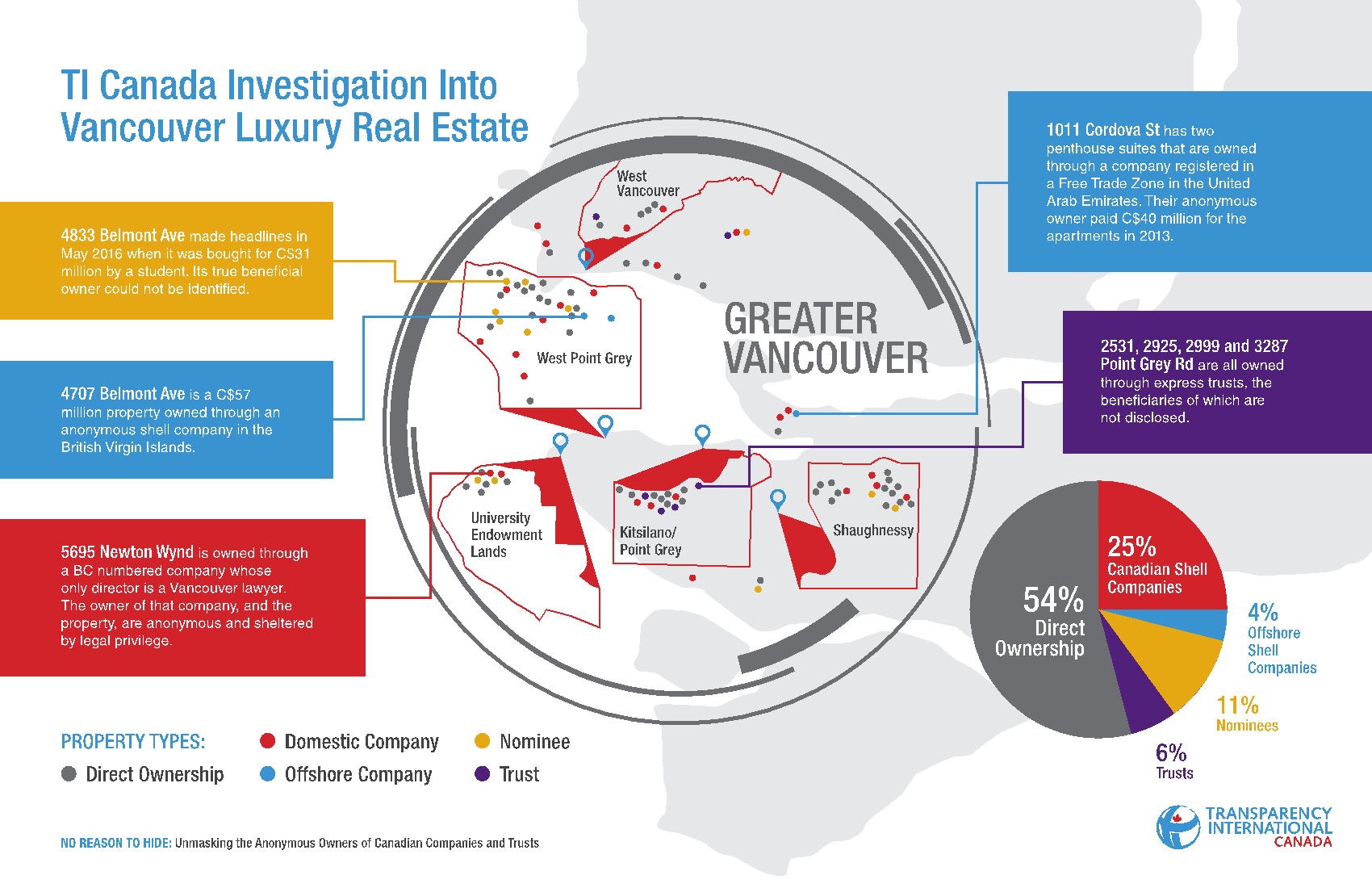

As part of its research for the No Reason to Hide report, Transparency International Canada examined the title documents for the 100 most expensive homes in Greater Vancouver, and found that nearly half of those properties – amounting to more than $1 billion in assets – do not have transparent ownership structures. Of the 100 properties, 29 are owned through holding companies (four of which are registered in offshore jurisdictions22), at least 11 are owned through nominees,23 and six are held in trust for anonymous beneficiaries.

Key findings

- The use of nominee titleholders is becoming more common. Of the 42 high-end properties sold in the last five years, 26 percent are owned on paper by students or homemakers. In contrast, only one of the 58 homes bought before 2011 is owned through an obvious nominee.

- Trusts have been used more by luxury property buyers in recent years. Titles for five of the six properties owned through disclosed trusts have been registered since 2011. As noted elsewhere in this report, there is no requirement to register trusts or even disclose their existence, so it is impossible to know how widely these arrangements are used.

- Holding companies remain a popular tool for beneficial owners of luxury property in Vancouver. This ownership model was used in 30 per cent of the titles registered in the past 10 years, as well as in 29 per cent of the total sample reviewed by Transparency International Canada.

A way forward

Despite making overtures in forums such as the G20 about improving transparency, we have done little to back those words with action at the federal level. Recent developments, such as the inclusion of AML reform and ownership transparency in the 2017 government budget, are encouraging. However, there is no need to wait on the federal government to introduce reforms, as much can be done at the municipal and provincial levels. For starters, beneficial ownership information should be included on property title documents.

Real estate professionals are well positioned to ask questions about their clients and the provenance of funds used for property purchases. They should be obligated to conduct due diligence on buyers and sellers, including efforts to identify beneficial owners. There is much more the government can do to assist real estate professionals in that regard. One big step would be to create a public registry of companies and trusts in Canada, and their beneficial owners. In doing so the government would provide the industry with an invaluable tool to verify the identities of their clients.

The police and regulators can also do more. Canadian real estate professionals’ compliance with AML rules will not improve unless those rules are enforced, and sanctions must be grave enough to act as a deterrent.

In the meantime, Canada’s opaque legal structures and lax approach to AML compliance and enforcement will continue to be exploited, distorting markets at home and giving us a bad name abroad.

Adam Ross is the principal of White Label Insights, a corporate investigations and due diligence consultancy, and is a member of Transparency International Canada's beneficial ownership working group.

Footnotes

1 FINTRAC, “Deter and Detect Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing: FINTRAC Annual Report 2014,” (p.12), http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/canafe-fintrac/FD1-2014-eng.pdf.

2 FATF, “Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures: Canada mutual evaluation report,” September 2016, (p.16), http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-Canada-2016.pdf.

3 Department of Finance Canada, “Assessment of inherent risks of money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada,” 2015, (p.32), http://www.fin.gc.ca/pub/mltf-rpcfat/mltf-rpcfat-eng.pdf.

4 FATF, “Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures: Canada mutual evaluation report,” September 2016, (p.16), http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-Canada-2016.pdf.

5 ibid

6 Cassidy Olivier, “$31.1-million Point Grey mansion owned by student,” Vancouver Sun, May 12, 2016, http://vancouversun.com/business/real-estate/31-1-million-point-grey-mansion-owned-by-student.

7 Andrew Yan, “Ownership patterns of single family homes sales on the west side neighborhoods of the City of Vancouver: a case study,” November 2015, http://www.slideshare.net/ayan604/ownership-patterns-of-single-family-homes-sales-on-the-west-side-neighborhoods-of-the-city-of-vancouver-a-case-study.

8 Stephen Schneider, “Money laundering in Canada: An analysis of RCMP cases,” Nathanson Centre for the Study of Organized Crime and Corruption, March 2004, http://www.csd.bg/fileSrc.php?id=560.

9 Mike Hager, “Potential solutions to deal with tax evasion in real estate market,” The Globe and Mail, September 18, 2016, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/vancouver/potential-solutions-to-deal-with-tax-evasion-in-real-estate-market/article31948354/.

10 Kathy Tomlinson, “Out of the shadows,” The Globe and Mail, September 13, 2016, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/vancouver/out-of-the-shadows/article31802994/.

11 Special purpose property holding companies may be accompanied by “bare trusts,” which are legal arrangements that enable a property to be managed for (and in many cases by) a beneficial owner without their name appearing on title.

12 Transparency International UK, “Corruption on your doorstep: How corrupt capital is used to buy property in the UK,” February 2015, http://www.transparency.org.uk/publications/corruption-on-your-doorstep/.

13 Louise Story and Stephanie Saul, “Stream of foreign wealth flows to New York real estate,” The New York Times, February 7, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/08/nyregion/stream-of-foreign-wealth-flows-to-time-warner-condos.html.

14 Richard Weiland, “The naked truth about trusts,” November 2009, http://www.cwilson.com/resource/newsletters/article/129-the-naked-truth-about-bare-trusts.html.

15 FINTRAC, “Trends in Canadian suspicious transaction reporting,” October 2011, http://www.fintrac-canafe.gc.ca/publications/typologies/2011-10-eng.asp; Alexandra Posadzki, “FINTRAC finds ‘very significant’ deficiencies at realtors in money laundering probe,” CBC News, September 14, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/fintrac-real-estate-money-laundering-1.3761343.

16 Transparency International, “Just for show? Reviewing G20 promises on beneficial ownership,” November 2015, (p.44), http://files.transparency.org/content/download/1936/12755/file/2015_G20BeneficialOwnershipPromises_EN.pdf.

17 Department of Finance Canada, “Assessment of inherent risks of money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada,” 2015, http://www.fin.gc.ca/pub/mltf-rpcfat/mltf-rpcfat-eng.pdf.

18 Alexandra Posadzki, “FINTRAC finds ‘very significant’ deficiencies at realtors in money laundering probe,” CBC News, September 14, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/fintrac-real-estate-money-laundering-1.3761343.

19 FINTRAC, “Indicators of money laundering in financial transactions related to real estate,” November 2016, http://www.fintrac-canafe.gc.ca/publications/operation/real-eng.asp.

20 Alexandra Posadzki, “FINTRAC finds ‘very significant’ deficiencies at realtors in money laundering probe,” CBC News, September 14, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/fintrac-real-estate-money-laundering-1.3761343.

21 FINTRAC, “Penalties for non-compliance,” http://www.fintrac.gc.ca/pen/1-eng.asp.

22 The offshore companies are registered in the British Virgin Islands (2), Hong Kong (1), and Dubai’s Jebel Ali Free Zone (1).

23 Title documents often list the occupation of the titleholder. Those who declared their occupation as “student,” “homemaker,” or “housewife” were assumed to be nominees.