by Frank Nasca, winner of the 2022 Paul Smith Memorial Award.

Brief statement regarding essay criteria:

This paper addresses themes of central importance in Canadian administrative law. I use mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to query how the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario’s institutional practices regarding early dismissals of applications are impacting access to justice and procedural fairness in Ontario’s direct access human rights system. In doing so, I discuss themes including the institutional competence of the Tribunal, the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and changing political priorities on Tribunal practices, and the experiences of self-represented litigants in administrative proceedings.

Disclaimer:

I wish to thank the Human Rights Legal Support Centre for their support in preparation of this paper. However, all opinions expressed are solely my own and do not reflect the opinion of the Human Rights Legal Support Centre. My views are based on my own independent research using sources I consider reliable.

I. Introduction

In 2008, the province of Ontario made systemic changes to the human rights system with a stated intention to address procedural delays and “shorten the pipeline from complaint to resolution by putting people at the front of the line with direct access to the human rights tribunal.”1 A primary feature of the amended Human Rights Code (“Code”)2 is the creation of this direct access model, which allows Applicants to file complaints under the Code directly with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (“the Tribunal”) for adjudication. Under the direct access model, the Tribunal is statutorily required to hear oral submissions from parties that bring a claim that is within its jurisdiction.3 However, fourteen years after the 2008 amendments, a significant portion of applications filed at the Tribunal are disposed of without an oral hearing. In the 2020-2021 fiscal year 2,582 cases were closed, only 55 of which were final decisions following a full merits hearing.4

While many cases are resolved at mediation or are voluntarily withdrawn by parties, there are other instances where the Tribunal uses mechanisms available under their Rules of Procedure (“Rules”) to dispose of applications without an oral hearing. This research considers one such mechanism – dismissals under Rule 13.1 for lack of jurisdiction. A Rule 13.1 dismissal is initiated by the Tribunal issuing a Notice of Intent to Dismiss (“NOID”) to an Applicant, most often before a Respondent is served with the Application or made aware of the allegations against them by the Tribunal.

This research investigates trends in the Tribunal’s use of Rule 13.1 NOIDs and considers what these patterns reveal about the institutional role of the Tribunal, access to justice, and procedural fairness in Ontario’s direct access human rights system. I start by situating Rule 13.1 NOIDs in the historical context and present structure of the human rights system in Ontario. I then make quantitative observations about the use of NOIDs across the human rights system as a whole. I present and analyze data about the Tribunal’s use of NOIDs from 2008-2021, revealing a sharp increase in the use of NOIDs starting in 2018. NOIDs become endemic in 2021. I then proceed to qualitatively analyze a random sample of 50 client flies from the Human Rights Legal Support Centre (“HRLSC” or “the Centre”). These Applicants received a NOID between July 1 and October 31, 2021 and contacted HRLSC for support. My analysis demonstrates that there are numerous instances whereby the Tribunal issued NOIDs to Applicants who have arguably disclosed a prima facie breach of the Code. I contend that these claimsfall within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, and therefore warrant an oral hearing. My paper concludes with a critical discussion about what the findings mean for Applicants, legal counsel, and others involved in Ontario’s human rights system.

A. Why is this topic timely?

My interest in this research grew out of my employment and clinical placement at the HRLSC. As a Juris Doctor candidate at Osgoode Hall Law School, I participated in a placement program with the HRLSC between May and December 2021. During my time there, the HRLSC was grappling with a notable increase in the number of people contacting them for support after receiving a NOID from the Tribunal. Some self-represented Applicants received NOIDs in instances where their narratives indicated violations of the Code, but the Applicant had struggled to clearly articulate the discriminatory acts in their HRTO Form 1 (“pleadings”).5 As a result of the observed increase in NOIDs and apparent shifts in the types of dismissals the Tribunal was making under Rule 13.1, the Centre expanded its services by offering access to interviews with legal counsel for Applicants that received a NOID (“NOID interview”).

The increase in NOIDs was observed anecdotally by many at the Centre. However, my own experience reading files where NOIDs were issued illustrated the amount of discretion the Tribunal holds in determining when to issue a NOID, and the apparent inconsistency with which this discretion is exercised. This concern arose from a pair of client files that I worked on in the summer of 2021. The two Applicants experienced the same allegedly discriminatory actions and filed separate applications with nearly identical pleadings, each alleging discrimination based on anti-Black racism. One of the files proceeded normally through the Tribunal process, but the second Applicant received a NOID, which stated:

A review of the Application and the narrative setting out the incidents of alleged discrimination fails to identify any specific acts of discrimination within the meaning of the Code allegedly committed by the respondent(s). The Tribunal does not have jurisdiction over general allegations of unfairness unless the unfairness is connected, in whole or in part, to one of the grounds specifically set out in Part I of the Code (e.g. race, disability, sex, etc.); see, for example, Forde v. Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2011 HRTO 1389).

This language is a standard template issued by the Tribunal, and as my research results demonstrate, it is the most frequent reason for dismissal observed at the Centre. These dismissal attempts, which I will refer to as “Forde NOIDs” because they cite Forde v. Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario6 (“Forde”), appeared even in cases where the client’s experiences did allege a prima facie breach of the Code.7 In the two aforementioned cases, I was able to work with HRLSC counsel to draft submissions responding to the NOID for the second Applicant, after which the application was permitted to proceed.

This prompted me to undertake this research. To ground my analysis of the NOID trends, I first describe the history and context of the human rights system in Ontario and discuss the role of NOIDs in the Tribunal’s Rules.

B. History of the human rights system in Ontario

Prior to the 2008 amendments to the Code, Ontario’s human rights system operated differently than it does today. The previous system relied on the Ontario Human Rights Commission (“the Commission”) to receive and investigate human rights complaints and determine whether a claim should be referred to the Tribunal for adjudication. Critics of this system referred to the Commission as a “gatekeeper,” because the Commission had the sole discretion to determine if complaints would proceed to the Tribunal, and “it could do so with or without conducting an investigation and without any requirement that there be a hearing.”8 In addition to the procedural fairness implications of a Commission-based system with no guaranteed right to an oral hearing, the system suffered from pervasive and significant backlogs. In the first reading of the proposed Bill 107: Human Rights Code Amendment Act, 20069 (“Bill 107”), Hon. Michael Bryant (the then Attorney General) stated:

Right now, it can take four to five years for a human rights complaint to go through the full complaints process, from intake, to witness interviews, to referral to the tribunal, to resolution. That’s not acceptable to this government and it’s not acceptable to the people of Ontario. The system is broken, and we in this Legislature have an opportunity to fix it.10

The proposal for a direct-access model had roots in the 1992 Cornish Report, the final report of a task force commissioned by Ontario’s New Democratic Party government under Premier Bob Rae.11 However, by the time Bill 107 was presented by Premier Dalton McGuinty’s Liberal government more than 15 years later, the NDP and other critics expressed concerns about the implications of a direct-access model on self-represented litigants in the human rights system.12 The Commission-based model had at least ensured that the Applicant had legal support throughout the process. The new direct access system enabled all claims to come before the Tribunal, but it also meant Applicants would not have Commission support through every stage of the complaints and adjudication process.

Despite concerns raised in Parliamentary debate, Bill 107 received Royal Assent on December 20, 2006, and Ontario’s new direct access model was ushered in. In addition to enabling Applicants to file complaints directly with the Tribunal, Bill 107 set up the HRLSC as an independent arm’s length agency to provide legal support to Applicants.13 The Commission remains one of the three pillars of the system, but no longer investigates claims and refers them to the Tribunal for adjudication – rather, the Commission serves as a policy and public education body to promote compliance with the Code.14

Although Bill 107 was introduced with the avowed intention of addressing systemic backlogs in the processing of human rights cases, current political and social contexts have resulted in a system where delays have once again become endemic. For several years after the 2008 reforms, indicia suggested that the reforms were achieving the goal of faster resolution of claims through the direct access model. For example, a 2014 study on the direct access model concluded, “the human rights system and the institutions created through the 2008 reform to the Code have resulted in the more timely resolution of claims,”15 and Andrew Pinto in the “Report of the Ontario Human Rights Review 2012” wrote “agreater volume of cases are resolved faster without a backlog developing and, for those cases that do not settle and proceed to a hearing, they are decided much faster.”16

The Tribunal’s Annual Reports from the years shortly after the reforms also showed that they were resolving claims rapidly. In the 2009-2010 year 95% of claims were resolved within one year of the application being accepted,17 declining to 62% in the 2010-2011 year18 and holding steady in the 55%-65% range over the 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 fiscal years.19 In the 2014-2015 fiscal year, Tribunals Ontario stopped reporting this specific metric, but continued to report service standards on the promptness of scheduling mediations and hearings, and on the issuing decisions post-hearing. The 2019-2020 year shows a marked decrease in the Tribunal’s ability to meet these performance measures: in that fiscal year, only 27% of cases had a first mediation date offered within 150 days of the date parties agreed to mediation (relative to 62% in 2018-2019, 84% in 2017-2018, and 92% in 2016-2017). Further, only 7% were offered a hearing date within 180 days of being ready to proceed to hearing (relative to 35%, 38%, and 34% in the three previous fiscal years, respectively).20 Figure 1 shows the Tribunal’s ability to meet its service standard goals of: (1) offering a mediation date within 150 days of the parties agreeing to mediation, and (2) offering a first hearing date within 180 days of the date the application is ready to proceed to hearing. These standards began to be reported in the 2013-2014 fiscal year, so Figure 1 begins with that year.

Figure 1: Tribunal’s ability to meet service standards related to the scheduling of mediations and hearings, 2013-202121

In a critical op-ed piece published in the Globe and Mail in January 2021, Raj Anand, Kathy Laird, and Ron Ellis22 report on this trend. They attribute it to several factors including the reduction of full-time adjudicators (from 22 to 11) under Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government (first elected in 2018), noting:

Expert human-rights adjudicators with excellent performance reviews have had their appointments prematurely discontinued when cabinet failed, without explanation, to renew their terms in the normal course. By the end of the first week in February [of 2021], there will be only three remaining full-time experienced adjudicators out of the 22 who were at the tribunal when the current government took over.23

Although the number of full-time adjudicators has increased since the op-ed piece was published, the concern Anand, Laird, and Ellis articulated with respect to the loss of expertise remains – many experienced former adjudicators with specific knowledge of human rights law are no longer with the Tribunal.

Issues related to delay and backlog were prevalent prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but like many institutions the Tribunal was profoundly impacted by the pandemic. The Tribunals Ontario 2020-2021 Annual Report notes that this impact was both substantive and procedural. Substantively, the Tribunal saw a shift in the composition of applications, with more applications coming forward in the goods, services, and facilities social area “largely related to the wearing of masks in stores, institutions and other public and private spaces.”24 From a procedural standpoint, case processing times increased to an average of 501 days (versus 419 days the year prior). The Tribunal notes:

Both adjudicative and operational processes, such as in person hearings, mediations, paper filing, printing and mailouts, were halted for a period of time while adjustments were made to transition to remote work environments and digital first delivery of services. Staff and adjudicative resources were also a challenge during this time.25

The Tribunal’s reported service standards reflect increasing procedural delays. While this paper cannot draw definitive conclusions about why the Tribunal has issued increased numbers of NOIDs over the same period that this trend is observable, one possible inference is that the Tribunal’s NOID practices have shifted to alleviate the significant backlog of cases. Thus, situating the work in the broader context of the Tribunal’s struggles to meet its service standards offers an important backdrop for this work.

C. What is a NOID, and what empowers the Tribunal to issue NOIDs?

Pursuant to s. 25.1 of the Statutory Powers Procedure Act26 and s 43(1) the Code,27 the Tribunal is empowered to create its own Rules of Procedure (“Rules”) to govern its practices and procedure in applying its statutory mandate. A NOID is the notice provided to an Applicant when the Tribunal is considering dismissing an application for lack of jurisdiction under Rule 13.1, which states:

13.1 The Tribunal may, on its own initiative or at the request of a Respondent, filed under Rule 19, dismiss part or all of an Application that is outside the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.28

From a procedural standpoint, a NOID is a very early dismissal attempt by the Tribunal. Although a NOID can be issued at the request of a Respondent, it is most often issued to an Applicant before a Respondent is served with the Application or made aware of the allegations against them.29 With respect to the contents of a NOID, the notice lays out the Tribunal’s jurisdictional concerns, typically using a set of standard templates identified in this work (see Results p 22 and Appendix A). The NOID also provides the Applicant with a deadline to provide written submissions in response.

In response to a NOID, an Applicant can make written submissions as to why their case falls within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. For a case to be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction, Tribunal jurisprudence has established that a plain and obvious test applies.30 In the leading case Masood v. Bruce Power (“Masood”) the Tribunal writes:

Rule 13.1 of the Rules of Procedure provides that the Tribunal may dismiss an application that is outside its jurisdiction. Rules 13.2 to 13.5 provide for a process under which the Tribunal may initiate a Notice of Intent to Dismiss on the basis of jurisdiction, which occurs without the application being sent to the respondent. Under the Tribunal’s jurisprudence, an application will only be dismissed at this preliminary stage if it is “plain and obvious” on the face of the application that it does not fall within provincial jurisdiction (emphasis added).31

While the Tribunal is not legally bound by its own precedent, continuity in Tribunal jurisprudence fosters consistency in the law.32 Accordingly, the Tribunal has applied the Masood test for Rule 13.1 dismissals over many years.33 The plain and obvious test is a threshold test with an exceptionally low burden on the Applicant, analogous to the plain and obvious test employed in motions to strike in civil proceedings. As Wilson J stated for the Supreme Court of Canada in Hunt v. Carey Canada Inc,

Thus, the test in Canada… [is] assuming that the facts as stated in the statement of claim can be proved, is it “plain and obvious” that the plaintiff's statement of claim discloses no reasonable cause of action? As in England, if there is a chance that the plaintiff might succeed, then the plaintiff should not be “driven from the judgment seat”. Neither the length and complexity of the issues, the novelty of the cause of action, nor the potential for the defendant to present a strong defence should prevent the plaintiff from proceeding with his or her case. Only if the action is certain to fail because it contains a radical defect…should the relevant portions of a plaintiff's statement of claim be struck out (emphasis added).34

A Rule 13.1 dismissal removes the Applicant’s procedural right to an oral hearing, so fairness requires that it be used only in cases where it is plain and obvious that the Tribunal lacks the jurisdiction to hear the matter. However, my research suggests that many applications that ought to pass the plain and obvious bar are being threatened with dismissal under Rule 13.1

In addition to understanding the correct legal test to apply under Rule 13.1, it is important to contextualize Rule 13.1 dismissals within other early disposition tools available to the Tribunal. To dispose of an application that does not warrant a full hearing on the merits, the Tribunal can also hold a summary hearing pursuant to Rule 19A, which reads:

19.1A The Tribunal may hold a summary hearing, on its own initiative or at the request of a party, on the question of whether an Application should be dismissed in whole or in part on the basis that there is no reasonable prospect that the Application or part of the Application will succeed.35

A summary hearing entitles the Applicant to procedural protections beyond what is offered by Rule 13.1, including the entitlement to an oral hearing. Accordingly, the legal test applied in a Rule 19A summary hearing differs from the test applied in a Rule 13.1 dismissal. The test comes from Dabic v Windsor Police Service (“Dabic”),36 and asks whether the application has a reasonable prospect of success. The test considers two lines of inquiry, which human rights lawyers Richa Sandhill and Emily Shepard call the “assumption element” and the “evidence element.”37 The test is as follows:

In some cases, the issue at the summary hearing may be whether, assuming all the allegations in the application to be true, it has a reasonable prospect of success. In these cases, the focus will generally be on the legal analysis and whether what the applicant alleges may be reasonably considered to amount to a Code violation [the assumption element].

In other cases, the focus of the summary hearing may be on whether there is a reasonable prospect that the applicant can prove, on a balance of probabilities, that his or her Code rights were violated. Often, such cases will deal with whether the applicant can show a link between an event and the grounds upon which he or she makes the claim. The issue will be whether there is a reasonable prospect that evidence the applicant has or that is reasonably available to him or her can show a link between the event and the alleged prohibited ground [the evidence element].38

The reasonable prospect of success inquiry is, by virtue of the enhanced procedural protections, a more rigorous test for the Applicant to meet than the plain and obvious test. However, my research indicates that the Tribunal is increasingly citing Rule 19A jurisprudence in dismissals under Rule 13.1, an issue which I take up in the Procedural Fairness portion of the Broader Implications section, infra.

Sandill and Shepard, writing in 2021, also noted that “Rule 19A has become the most frequent generator of early dismissal case law at the HRTO.”39 My research demonstrates that NOIDs are an increasing generator of early dismissal attempts. They raise particular concerns about the Tribunal’s institutional role, access to justice, and procedural fairness beyond those generated in the context of Rule 19A summary hearings.

II. Research Questions and Methods

This is a mixed methods study that addresses two primary research questions:

- How has the Tribunal’s use of NOIDs quantitatively shifted from 2008-2021?

- How has the Tribunal’s use of NOIDs quantitatively shifted from 2008-2021?

With respect to quantitative shifts, I present and analyze data obtained directly from Tribunals Ontario via a Freedom of Information (“FOI”) request.40 This includes annual data on the total number of applications filed, total number of NOIDs issued, and total number of summary hearings held between 2008-2021.

For the qualitative component, I started with a random sample of 50 client cases that booked NOID interviews with the HRLSC between July 1 and October 31, 2021.41 To collect this sample, the HRLSC provided me with an Excel report of all NOID interviews booked in the relevant timeframe. I cross-checked this list by asking if the HRLSC was aware of any other NOID interviews in the relevant timeframe, acknowledging that sometimes interviews are miscategorized at the intake and booking stage. This yielded a sample of 79 cases. Due to time constraints, I then selected a random sample of 50 cases via an online sampling tool.42

Once my sample was set, I assigned each client an anonymous numerical alias and pulled relevant information and documents from each client file, including:

- The Form 1 (the initial application to the Tribunal, which forms the basis of the pleadings in each case in front of the Tribunal)

- The NOID issued to the Applicant

- Notes from NOID interviews with counsel, and follow-up summary legal advice (if applicable)

- The retainer outcome of the NOID interview

- Submissions filed in response to the NOID (if applicable)

- Any subsequent correspondences with the Tribunal and/or the Respondent, if applicable, including (but not limited to) the outcome of the NOID submissions

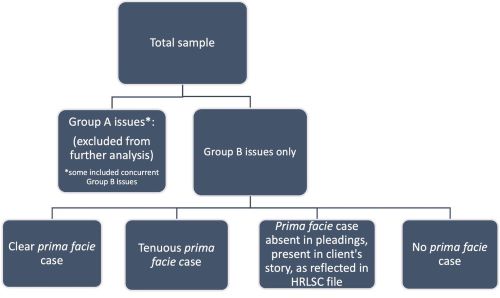

I then reviewed this information and analyzed the cases on criteria including: the reasons for dismissal cited in the NOID, the grounds and social areas plead, and the outcome of NOID submissions. My review revealed that some reasons for dismissal cited in the NOIDs disclosed what I consider a bright line jurisdictional issue, such as constitutional (federal versus provincial) jurisdiction, lack of connection to the province of Ontario, limitation periods, or other issues that clearly placed an application outside of the Tribunal’s jurisdiction on a plain reading of the Code. I considered these issues “Group A issues”. Others revealed a more complex and discretionary interpretation of the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. These issues included, inter alia, a lack of a clear nexus between the Code ground plead and the alleged mistreatment, incoherency in the narrative, and unclear connection to a social area protected by the Code. I considered these “Group B issues,” or issues that I felt warranted closer inspection to determine whether the plain and obvious test was being consistently applied. I note Group A and B issues can appear together, and some cases had reasons for dismissal that fell into both categories. However, for the purposes of the next stages of analysis, I chose to exclude any case that had a Group A issue from further analysis. I did so because I am less concerned about access to justice and procedural fairness issues arising from NOIDs being issued in cases where there is a clear statutory or constitutional basis for the Tribunal to claim a lack of jurisdiction.

For cases that disclosed only Group B issues, I conducted a closer reading of the pleadings in the Form 1 to determine if they revealed a prima facie breach of the Code.43 Although the prima facie case test is a higher burden for the Applicant to meet than the plain and obvious test, my operating assumption in conducting this analysis was that for cases without a bright line jurisdictional issue, the existence of a prima facie case indicates it is not plain and obvious that the application falls outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. In light of the serious procedural fairness implications of dismissing applications without a right to an oral hearing, and considering that many Applicants self-draft their pleadings, I favored a generous reading of the pleadings and assumed all facts as plead were true. This generous reading of the pleadings is also in line with the plain and obvious test, as articulated in the Tribunal’s jurisprudence and analogous civil procedure contexts.

I then further sorted Group B cases into: (1) cases which contained a clear prima facie case, (2) those which contained a tenuous prima facie case, and (3) those which contained no prima facie case. A fourth category emerged as I classified cases: some cases contained no prima facie case in the Applicant’s self-drafted pleadings, but once the client met with counsel for the NOID interview it became evident to counsel that they could likely establish a prima facie case but had drafted their application poorly.

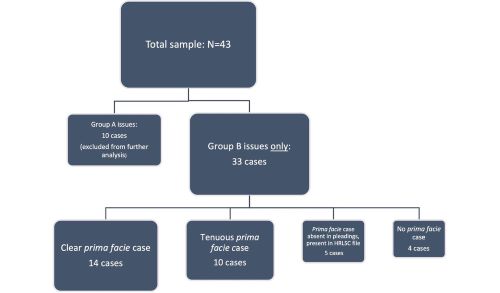

Figure 2 provides my taxonomy of cases throughout the analysis. This figure appears at the end of the “Results” section with the total number of cases that fell into each category.

Figure 2: Categorization of cases through the stages of analysis

After this initial categorization of each case, I looked for trends that cross-cut the set of Group B cases that provide insight into the following questions:

- Is the Tribunal using NOIDs to dismiss cases that ought to proceed, at least past the plain and obvious test to an analysis of reasonable prospect of success at the summary hearing stage?

- Is the Tribunal expanding the scope of dismissals for “jurisdiction” in a manner that ought to concern human rights practitioners and users of the human rights system?

- Are certain types of Applicants or allegations at an elevated risk for dismissal under Rule 13.1?

A. Limits, challenges, and caveats to the methods

I note that the conclusions I reach in response to these questions are qualitative and based on a limited sample of cases. My sample reflects only applicants that sought support from the HRLSC. For these reasons, there are limitations to the methods. Notably, these qualitative observations cannot be assumed to apply across the human rights system as a whole.

Further, I based my determination about whether a prima facie case can be made out on my analysis and that of the HRLSC counsel that conducted the NOID interview with the Applicant. Therefore, I cannot claim that the conclusions that I have drawn about whether a case discloses a prima facie breach are the only possible reasonable or correct conclusion – however, the issuance of NOIDs by the Tribunal similarly involves a high degree of discretion by the decision-maker. The determination of jurisdiction will often turn on a single person’s perception and analysis of the pleadings, so the limits of this type of analysis might also be reflected in the Tribunal’s practices.

This research is the first attempt at understanding the Tribunal’s use of NOIDs on a widespread scale and offers important insights for Applicants, human rights practitioners, and future researchers. The combined qualitative and quantitative approaches taken in this research begin to create a picture of how the Tribunal is using Rule 13.1 NOIDs.

III. Results and Discussion

A. Quantitative results & discussion: How has the use of NOIDs shifted from 2008-2021?

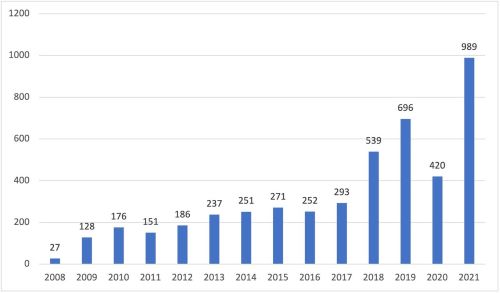

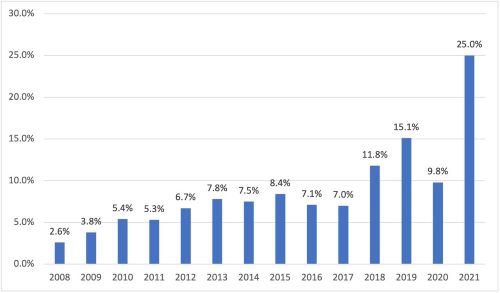

The quantitative data received through my FOI request confirms the trend observed by the HRLSC – the Tribunal is issuing NOIDs at an increased rate. For the first nine years of the direct access model (2008-2017), the Tribunal issued fewer than 300 NOIDs annually. However, in recent years there have been two periods of significant growth in the number of NOIDs issued. The first occurred in 2018, when the number of NOIDs issued roughly doubled. The second occurred in 2021, when the number of NOIDs climbed well above any other year on record, reaching 989 NOIDs (comprising 25% of the total number of applications received that year).

I note that 2020 shows a decrease in the number of NOIDs issued. As previously noted, the Tribunal suspended operations during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, starting in March 2020. I presume that this impacted the number of NOIDs issued that year. It is possible that the increase in NOIDs in 2021 reflects some NOIDs that might have been issued in 2020 if not for the COVID-19 suspension. Notwithstanding this, the combined 2020 and 2021 total still exceeds the combined total of 2018 and 2019 by 174 NOIDs, or 114%. This is particularly concerning because the 2018 and 2019 years already saw a twofold increase over any other prior years. The number of NOIDs issued annually from 2008-present is reported in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the number of NOIDs issued as a percentage of the total number of applications received each year.44

Figure 3: Number of NOIDs issued annually, 2008-202145

Figure 4: Number of NOIDs issued annually as a percentage of total applications received, 2008-202146

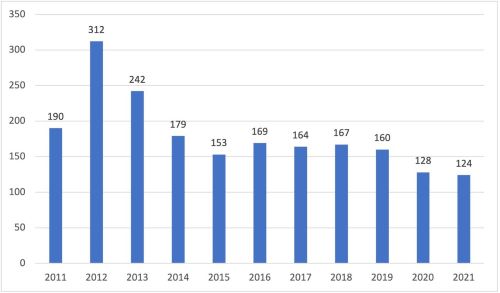

Lastly, I considered how trends in the Tribunal’s use of NOIDs compare to the trends in the use of Rule 19A summary hearings. Summary hearings are a useful comparator because they are an alternative avenue to dispose of potentially low merit cases, while affording Applicants a higher degree of procedural fairness. They are also the appropriate avenue to apply the “no reasonable prospect of success” test that has seemingly usurped the “plain and obvious test” in the Tribunal’s analysis of NOID files (discussed in Broader Implications, infra). Thus, in my FOI request I asked for the total number of notices of summary hearing issued annually. Tribunals Ontario modified this request (with my consent) to the total number of summary hearings held annually from 2008-2021.

Tribunals Ontario data revealed that the Tribunal held its first summary hearing on August 6, 2010, so I have omitted the 2008, 2009, and 2010 years from the summary hearing analysis to focus solely on years with a full 12 months of potential hearings. In the same period that dismissals under Rule 13.1 increased, there was a decrease in the number of summary hearings held – 2020 and 2021 had the lowest number of summary hearings on record of all the relevant years. This is possibly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, although operations resumed by mid-2020 and the Tribunal shifted to remote videoconference hearings.47 The year with the fewest summary hearings on record is 2021, during which operations were not suspended at any point. The total number of summary hearings held annually is presented in Figure 4. Also notable is that in 2021, 124 summary hearings were held whereas 989 NOIDs were issued.

Figure 5: Total number of summary hearings held annually, 2011-2021.

The data from Tribunals Ontario give a quantitative underpinning to the trends observed by the HRLSC. The use of NOIDs has increased significantly since 2018, with 2021 showing the most marked increase. Given that the Tribunal’s statutory jurisdiction did not change in the same period, a qualitative analysis of cases in which the Tribunal issued NOIDs seemed the most appropriate method for understanding how the Tribunal’s interpretation of its jurisdiction and its application of Rule 13.1 has been borne out in individual cases. The following qualitative analysis investigates what trends can be observed about the Tribunal’s use of Rule 13.1 NOIDs in the year 2021.

B. Qualitative results & discussion: Analysis of the use of NOIDs in HRLSC-involved cases: July 1, 2021 – October 31, 2021

As noted in the Methods section, supra the qualitative analysis started with a random sample of 50 clients that came to HRLSC for legal support after receiving a NOID between July 1, 2021 and October 31, 2021. Of these initial 50, six client cases had a legal issue related to a different procedural point in the Tribunal process. These cases were excluded from analysis. One client withdrew from the receipt of HRLSC services. Therefore, for the purposes of this analysis, n=43.

The first step in analysis for each case was to identify the reasons for dismissal given in the NOID. When the Tribunal issues a NOID, the reasons for dismissal are delivered using what appear to be boilerplate templates for various dismissal types. In the set of 43 cases, 14 different reasons for dismissal were observed. Outside of my sample, there may be other reasons for dismissal cited by the Tribunal in NOIDs. The full language for each type of dismissal I observed is included as Appendix A. I grouped these dismissal types into two conceptual categories: Group A issues (clear jurisdictional issues with a readily identifiable statutory or constitutional basis) and Group B issues (reasons for dismissal that appeared more discretionary, and that I felt warranted further investigation). By making this grouping, I do not suggest that these categories are perfectly delineated: for example, in some instances, a case with only Group B issues did, on closer inspection, contain legitimate jurisdictional issues that were evident in the pleadings. Likewise, there was at least one instance where an application I excluded from further analysis on the basis that the NOID alleged a clear jurisdictional issue was – on the assessment of Centre counsel in their interview notes – wrongly issued the NOID on a misapprehension of the Applicant’s pleadings.

Although this categorization is imperfect, it was intended to exclude any file that disclosed a clear jurisdictional issue from further analysis. These issues would likely pass the plain and obvious test since there is a statutory or constitutional bar to the Tribunal considering the claim. On the other hand, I found that reasons for dismissal given in the Group B category were often the result of a self-drafted Applicant struggling to clearly make their case. A determination that an application falls into one of these categories involves some interpretive discretion on the part of the decision-maker. Further, in the Group B cases, the applicant is uniformly pleading that some discrimination has occurred – even in an instance where the Tribunal may not see the nexus between the ground and social area on the facts provided, the Applicant must have (by the very nature of the Tribunal’s Form 1) selected specific grounds and social areas in order for their application to have proceeded to this stage. In other words, dismissals in this category require the decision-maker to read the pleadings and determine if, assuming all facts as plead are true, it is plain and obvious that the Application falls outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction despite the elements of a prima facie case being formally “checked off” in the Applicant’s Form 1. About half of the files (22 out of 43) cited more than one reason for dismissal, with issues sometimes cross-cutting my two broad categories. The dismissal types in each category are as follows:

Group A Issues:

- Constitutional jurisdiction (“CJ”): The issue is in the federal jurisdiction pursuant to the Constitution Act, 1867

- Standard limitation period issue (“LP(S)”): The application is filed outside of the one-year limitation period set out in the Code, and there does not appear to be good faith delay

- Section 45.1 of the Code (“45”): The issue has been dealt with in another legal forum and ought to be dismissed pursuant to s 45.1 of the Code

- Section 46 of the Code (“46”): A civil proceeding has been initiated or is ongoing, and the application ought to be dismissed under s. 46 of the Code

- Provincial jurisdiction (“PJ”): The events occurred in another province and do not appear to be connected to Ontario

- Adjudicative immunity (“AI”): The respondent is an arbitrator, adjudicator, or judge and is protected by adjudicative immunity

- Counsel conduct (“CC”): The issue relates to the conduct of a lawyer representing a party in another legal proceeding, which is not covered by the Code

Group B Issues:

- General allegations of unfairness, citing Forde v. Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario48 (“Forde”) (“FD”): The application fails to identify specific acts of discrimination within the meaning of the Code

- Bald assertion (“BA”): There is no clear factual basis which links the respondent’s conduct to the Applicant’s ground(s) claimed

- No social area (“SA”): The application does not appear to fall under a social area protected by the Code

- No coherent narrative (“CN”): The application fails to set out a coherent narrative that explains the particulars of the alleged discrimination

- No Reprisal (“NR”): The Applicant has plead the ground of reprisal, but has failed to demonstrate reprisal

- Limitation period (potential drafting issue, the Tribunal cannot identify the act of discrimination alleged in question 7) (“LP(7)”): The last event of discrimination identified in Question 7 of the Form 1 is unclear or not clearly connected to the Code.49

- COVID-19 mask case:50 medicals required (“C19”):The application states a medical exemption from mask wearing. The applicant must provide evidence of disability to proceed.

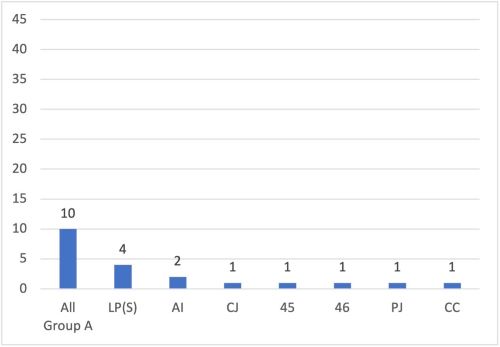

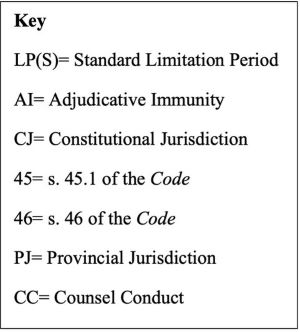

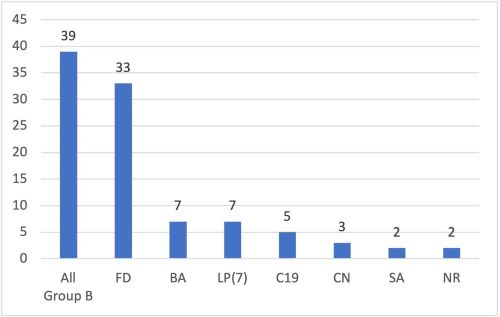

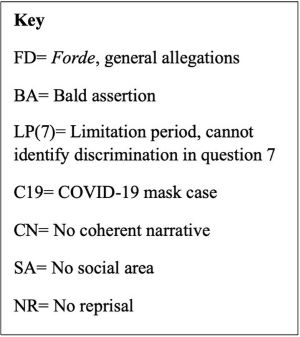

Of the 43 cases, 10 received NOIDs identifying issues in the Group A category. Thirty-nine of the cases received NOIDs identifying Group B issues, but six of these also displayed concurrent Group A issues. Therefore, four had solely Group A issues, and 33 had solely Group B issues. By a significant margin, the most frequently cited issue was the “general allegations of unfairness” category (“FD”), with 33 of 43 cases citing this reason for dismissal. The breakdown of the frequency each reason for dismissal is found in Figures 6 and 7.

Figure 6: Frequency of Group A issues

Figure 7: Frequency of Group B issues

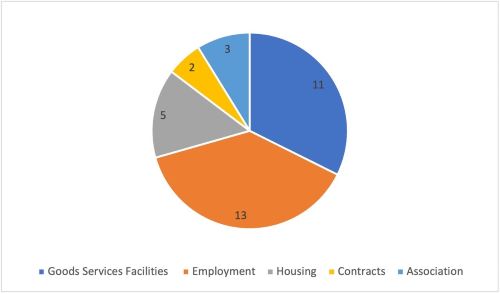

This distribution of the reasons for dismissal in my sample indicates that Group B issues – the issues I found involved more discretion on the part of the decision maker – far outweigh the clear jurisdictional issues in Group A. The 33 cases with only Group B NOIDs were further analyzed. These 33 cases covered all five social areas covered by the Code – employment, housing, contracts, vocational associations, and goods, services, and facilities (“GSF”). The social area breakdown in this sample had a greater emphasis on employment and GSF, which is consistent with overall Tribunal statistics.

Figure 8: Number of Group B files by social area

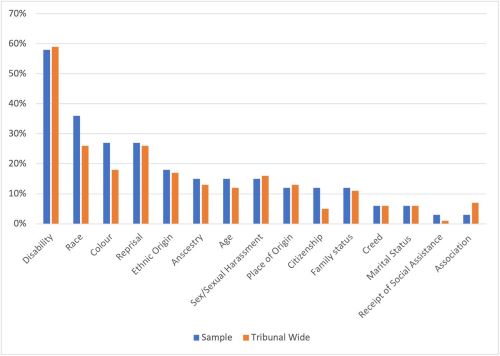

Within the subsample of 33, I also analyzed which grounds were plead. Race-related grounds51 – especially race, colour, and citizenship – were overrepresented in this sample relative to Tribunal-wide trends. All other grounds found within this sample tracked relatively closely to the Tribunal-wide trends, as reflected in the Tribunal’s 2021-2021 Annual Report. Although my data is not statistically significant, further research could determine if Applicants pleading racial discrimination are at greater risk of dismissal under Rule 13.1.

I also note that some grounds were not represented at all in this sample – including sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and record of offences, which make up 4%, 6%, 3%, and 2% of claims received by the Tribunal in 2021-2022, respectively.52 This omission could be a function of my small sample size or of the relatively small portion of claims filed under these grounds, or there could be other phenomena contributing to this trend. Further research with more sophisticated and statistically significant methods is required to reach a conclusion.

Additionally, 23 of the 33 cases (or roughly 70%) were filed by Applicants that plead multiple grounds of discrimination, indicating that Applicants in this sample are more likely to allege discrimination based on multiple Code-based identities, as opposed to alleging discrimination based on a singular Code-protected trait. The Tribunal does not report on the intersectional nature of applications received – the Annual Reports only give a percentage breakdown by each individual ground. However, in this subset of cases individuals pleading intersectional or additive claims are represented in greater numbers than cases where the person identifies only a singular Code-protected trait. Further research could establish if intersectional or additive claims are at an elevated risk for a Rule 13.1 dismissal.

Figure 9: Frequency each ground was plead by percentage, relative to the Tribunal’s 2020-2021 Annual Report

The final step in analysis was reading the pleadings for each of the 33 cases in the sub-sample to determine if the three elements of a prima facie case were discernable in the pleadings. With respect to each of the three elements of a prima facie case – a Code-protected ground, adverse impact within a social area, and a nexus between the two – I identified if the element was (1) clearly present within the pleadings, (2) arguably or tenuously within the pleadings, or (3) absent from the pleadings. In instances where the element was absent or tenuous, I reviewed notes from NOID interviews, follow-up summary legal advice, and NOID submissions filed with the Tribunal to ascertain if the element did, in fact, form a part of the client’s allegations. A prima facie Code breach forming part of the Applicant’s experience but not being articulated in the pleadings is an access to justice issue because the 2008 direct access model was intended to present minimal barriers to Applicants. However, in implementing the model Applicants with human rights issues in front of the Tribunal also lost access to Commission support throughout the process. As a result, at the time of the 2012 Pinto Report 54% of Applicants were self-represented at mediations and 53% at hearings in front of the Tribunal.53 At the application stage, 70% were unrepresented.54 Respondents, on the other hand, were “almost always represented.”55 Self-represented Applicants may not have the legal knowledge necessary to turn their experiences into a succinct and compelling legal narrative within the prima facie case framework. Without that expertise, they stand at a disadvantage to represented Respondents.

With respect to my assessment of the strength of the claim, I found that 14 of the 33 Group B cases disclosed a clear prima facie case. In order to be categorized as a clear prima facie case, I assessed each of the three elements of a prima facie case separately and found that all three were clearly present. If I identified any of the three elements as tenuous, the case was considered a tenuous case. If I identified that an element was absent, I determined that there was no prima facie case. Following this analytical structure, 10 contained a tenuous prima facie case, and four contained no arguable prima facie case. In another five, there was no prima facie case discernable in the written pleadings, but after reviewing NOID interview notes with counsel and NOID submissions, I concluded that the Applicant could feasibly establish the three elements of a prima facie case but was unable to articulate this in their written pleadings. The element that applicants most frequently struggled to establish was the nexus between their plead grounds and the mistreatment they experienced. Figure 10 recalls the categorization of cases described in Figure 2 (in the Methods section, supra), but provides the total number of cases found in each category throughout the full analysis.

Figure 10: Final categorization of cases

I also tracked whether the HRLSC was retained to draft written NOID submissions on behalf of the client. I looked at the impact of those submissions on whether the case was dismissed or processed through the next step of service on the Respondent. There HRLSC considers numerous factors when deciding whether to offer a retainer, and thus the number of retainers offered should not be assumed to correlate with the number of potentially meritorious claims. However, HRLSC offered retainers in 11 of the 33 cases, and in one additional case at the reconsideration stage after the Applicant self-drafted NOID submissions that failed to convince the Tribunal that their application was within jurisdiction. At the time of writing, every case that the HRLSC supported through a NOID submission retainer has proceeded through to service on the Respondent.

In analysing the pleadings, I also made several other observations that are notable from an access to justice or procedural fairness standpoint. These related to the Tribunal’s perception of race-related claims as “general allegations of unfairness,” the importance of a succinct and well drafted narrative, and the Tribunal’s treatment of COVID-19 masking cases. Each of these may warrant future research.

In addition to race-related grounds being overrepresented in the subsample overall, they overrepresented amongst applications that received a Forde NOID for “general allegations of unfairness,” but (on my analysis) revealed a prima facie case. Thus, applicants pleading race-based grounds may be at elevated risk of dismissal via the Tribunal viewing their allegations as merely “general allegations of unfairness.” This was particularly the case in Applications where I interpreted the allegations to be instances of complex, systemic, or subtle allegations of racial discrimination.

A succinct and compelling narrative is a factor that may help Applicants avoid receiving a NOID. Lengthy (in excess of 5 pages for the core narrative) and/or inexpertly drafted Form 1 narratives may be at elevated risk of dismissal as general allegations of unfairness or for a lack of a coherent narrative. This is particularly the case if the Applicant’s narrative includes some non-Code allegations alongside some potential Code violations. Some Applicants will describe multiple experiences with the Responent(s), and only some of these are potentially acts of discrimination under the meaning of the Code. However, under the plain and obvious test, if there is even a single alleged violation of the Code I argue that the Application ought to be permitted to proceed.

In the context of COVID-19 masking cases, the Tribunal appears to have departed from its established practices regarding the need to provide medical documentation for a disability claim at the pleading stage. COVID-19 NOIDs require that Applicants provide medical documentation for their application to proceed past the NOID stage, even though the applications often allege a prima facie breach and the Form 1 states that documentary evidence is not required at the application stage. Although many of these cases potentially lack merit because jurisprudence from during the COVID-19 pandemic has found that there are many allegations in which Applicants do not have disabilities under the meaning of the Code and/or that alternative service options like curbside pickup constituted a reasonable accommodation,56 from a jurisdictional perspective these cases do not fail the plain and obvious test. The plain and obvious test requires that the decision-maker assume all facts as plead are true, and thus should assume that the Applicant has the disabilitie(s) they claim. While they may not be able to make out a Code breach on balance, these issues would be more appropriately adjudicated at a Rule 19A summary hearing or merit hearing.

IV. Broader Implications

My qualitative analysis rests on a relatively small sample size (50 out of 989 NOIDs issued in 2021, or about 5% overall, and about 65% of the NOIDs received by HRLSC between July 1 and October 1, 2021). It is also constrained by the methodological limitations discussed above. However, taken with the observed increase in the use of NOIDs across the human rights system as a whole, the data reveals concerns related to of access to justice, procedural fairness, and the Tribunal’s institutional role.

A. Access to justice: Self-represented litigants at higher risk of dismissal

In my qualitative analysis, a striking pattern emerged regarding the Tribunal’s treatment of inexpertly drafted submissions versus expertly drafted submissions. Every case in my sample in which the HRLSC was retained to draft NOID submissions proceeded to service on the Respondent rather than being dismissed. The same is true in the anecdote of the two cases that spurred my interest in this research, discussed in the Context section, supra. With the support of the HRLSC, the second file in the pair of cases I discussed at the opening of this paper proceeded to service on the Respondent.

One of the stated goals of the direct access model was to increase access to justice, but I contend that in order to achieve this goal the Tribunal must take a generous reading of self-drafted submissions. The Tribunal should err on the side of providing Applicants with their statutory right to an oral hearing in cases where it is not plain and obvious that the application is outside the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. This may require the Tribunal to draw reasonable inferences from the narrative that will help them establish the nexus between the grounds plead and the adverse treatment described. If this nexus does not exist on the facts, this will become evident under the no reasonable prospect of success test at summary hearing or during a full hearing on the merits. My research turned up 11 instances in which the HRLSC was retained, and their submissions enabled the Tribunal to see that it is not plain and obvious that the allegations were outside their jurisdiction. Although the sample is small, this observation poses a significant access to justice issue for self-represented litigants in Ontario’s direct access human rights system.

B. Procedural fairness concern: Importing the Dabic framework into the jurisdiction analysis

The high number of “Forde NOIDs” in my sample suggest that the Tribunal’s interpretation of its jurisdiction and the legal tests it applies to determine jurisdiction may be changing, and this trend concerns me from a procedural fairness standpoint. The denial of the statutory right to an oral hearing raises procedural fairness concerns because the Applicant has a lesser opportunity to make their case. My quantitative analysis suggests that Tribunal has seemingly begun to apply principles from the Rule 19A summary hearing framework to their preliminary analysis of jurisdiction, which in turn allows more cases to be dismissed without an oral hearing.

A fulsome analysis of this phenomenon is outside of the scope of this paper and would require more detailed analysis of the administrative law principles underlying the Tribunal’s exercise of its statutory powers and its ability to determine the limits of its jurisdiction. However, I will lay out the basis of the argument for future researchers or practitioners to consider. This argument can be understood by looking at some of the caselaw that is frequently cited in the NOIDs. Of the 43 cases I analyzed, 33 cited Forde and claimed that the Tribunal does not have jurisdiction over general allegations of unfairness. Thus, Forde is a useful starting point for this analysis.

First, I note that Forde was a decision rendered in the context of a 19A summary hearing. As such, the Applicant had an oral hearing, and the Tribunal applied the no reasonable prospect of success analysis developed in Dabic. In fact, the Forde decision does not discuss jurisdiction at all – at paragraph 17 the Tribunal writes, “the Tribunal does not have the power to deal with general allegations of unfairness,”57 a phrase which has been re-styled to “the Tribunal does not have the jurisdiction to deal with general allegations of unfairness” in the Forde NOID template (see Appendix A). This wording change on its own is minimal and may not appear concerning given the proximity in the meanings of the words “power” and “jurisdiction.” However, the paragraphs immediately following this statement in Forde articulate my concern with importing the Forde/Dabic framework into the Rule 13.1 context. The Tribunal goes on to discuss how the concept of prima facie discrimination is “not helpful in interpreting the Tribunal’s summary hearing rule” and that the parties ought to focus on the no reasonable prospect of success analysis.58 In other words, different analyses reign for different points in the Tribunal’s procedures – particularly at the prima facie case stage versus the summary hearing stage. Thus, I contend that the Tribunal ought not import the findings from Forde into a basis for a Rule 13.1 dismissal.

Looking at the historical context of Rule 13.1 dismissals pre-2018 supports this concern that there is slippage in the meaning of “jurisdiction” within HRTO caselaw.59 The cases which developed the plain and obvious test in Tribunal jurisprudence were related to clearer jurisdictional issues, such as timeliness or territorial jurisdiction.60 It appears to me that the Tribunal is now styling issues that may, in fact, be better treated as issues of merit as issues of jurisdiction.

My concern with the shifting interpretation of “jurisdiction” is further underscored by the “bald assertion” NOIDs – a type of NOID that began in the latter part of my July-October 2021 timeframe (see Appendix A). This NOID type cites Forde as well as a more recent case (Groblicki v. Watts Water, 2021 HRTO 461, in turn citing Forde), for the principle that “a bald assertion that the adverse treatment the applicant received was owing to their enumerated ground is not enough to provide the required factual basis” to bring an application within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. In my view, this “factual basis” is not a jurisdictional issue, but an assessment on the merits. In many cases, a finding of discrimination may turn on the Applicant’s assertions because direct evidence of discrimination can be difficult to establish – particularly in instances of subtle or systemic discrimination. It is precisely in these cases – where the outcome may turn on the credibility of the parties – that an oral hearing is the most necessary for the just resolution of the dispute.61 What appears to be a bald assertion on the face of the application may become far less “bald” when the adjudicator solicits the evidence and hears examination and cross-examination of the parties. Further, the Tribunal’s own jurisprudence has previously determined that allegations do not need to be “well founded”62 to fall within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. Notwithstanding this fact, a CanLii search on March 7, 2021 revealed that the exact phrase: “To fall within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, an Application must provide some factual basis beyond a bald assertion” appears in in 50 reported decisions, all in 2021 and 2022. The phrase “To fall within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, an Application must provide some factual basis beyond speculation” appears in in 18 reported decisions, again all in 2021 and 2022.

I am concerned with how the Tribunal has begun to apply the Rule 19A summary hearing framework to their preliminary analysis of jurisdiction. Through applying a higher threshold test, the Tribunal’s interpretation of its own jurisdiction appears to have shifted, leading the Tribunal to decline jurisdiction in cases that may be properly before it. These findings deserve deeper legal analysis, including more research about the impetus for the Tribunal’s changes in NOID issuing practice and their interpretation and application of Rule 13.1.

C. Institutional role of the tribunal

Lastly, the Tribunal’s current use of NOIDs raises concerns about the Tribunal’s proper institutional role within the direct access model. As discussed in the History of the Human Rights System of Ontario section, supra,amongst the stated intentions for the 2008 reforms was removing the Commission as a “gatekeeper” to adjudicating human rights claims. The corollary to this is s. 43(2) of the Code, which requires the Tribunal hear oral submissions on any matter falling within its jurisdiction. I argue that the Tribunal’s increasing attempts to dismiss cases under Rule 13.1 have led it to act in a gatekeeping role beyond that contemplated by s. 43(2) of the Code. While the Tribunal has a high degree of discretion and independence in developing its own processes and rules of procedure, this should not be exercised in a manner that undermines the Tribunal’s proper institutional role and statutory mandate. If the Tribunal is dismissing cases that are properly within its jurisdiction, then the current human rights model is not functioning as intended – Applicants are not benefitting from direct access to an oral hearing for all matters within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction.

V. Recommendations for practitioners and future research

This work is preliminary and it is limited in its methods. Several trends identified in this work require more in-depth analysis to reach definitive conclusions, and others warrant careful attention to determine the ways that the effects observed are being produced. For this reason, I suggest that researchers with a larger budget and more time consider a larger sample size and develop more sophisticated methods, particularly methods that will yield statistically significant results. Future research can examine possibilities raised in my Results and Discussion section, such as whether intersectional and/or race-based cases are at a higher risk of dismissal under Rule 13.1.

Additionally, this research identified when the Tribunal started using NOIDs with greater frequency but could not draw conclusions as to why this trend began when it did. Future researchers may consider submitting more targeted FOI requests to learn about the factors involved internally in creating the trend observed, including requests for policy discussions and internal practice directives at the Tribunal that may have prompted the increase in NOIDs. I note that in 2018, the Tribunal publicly issued a Practice Direction on New Case Processing System and Case Management Conference Calls.63 While the Practice Direction does not mention NOIDs or issues of jurisdiction, the first increase in NOIDs was observed during the same year. More targeted FOI requests could probe internal discussions that occurred at the Tribunal to discern if there was a targeted effort to shift the use of Rule 13.1 dismissals tied to the introduction of the new case management system.

With respect to some of the legal questions raised around procedural fairness and the Tribunal’s proper interpretation of its jurisdiction, input from the courts may be valuable in determining the boundaries of the Tribunal’s institutional role and interpretation of jurisdiction. For this reason, researchers and lawyers may wish to consider administrative law grounds for judicial review. Because this trend is widespread, I would recommend the careful selection of test case(s) to file for judicial review to help resolve some of the potential legal questions raised. Following Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v Vavilov, questions of jurisdiction are no longer a categorical question to be reviewed on a correctness standard and are thus subject to the presumptive reasonableness standard.64 This may pose strategic difficulties in seeking judicial review of the Tribunal’s decline of jurisdiction through Rule 13.1, but I leave the question of legal strategy to litigators with particular clients and facts in front of them.

Perhaps most importantly, Applicant-side human rights lawyers can apply the findings of this research to help ensure that clients’ applications face less risk of Rule 13.1 dismissals. Applicant counsel should advise clients that it is imperative to establish a clear nexus between the grounds plead and the adverse impacts claimed at the pleadings stage. The Tribunal’s Form 1 asks applicants to describe what happened, who was involved, when it happened, and where it happened for each alleged event. I advise that applicants should also focus on a silent fifth question: how or why do you know that your (race/gender/age/disability/etc.) was a factor in this event?

However, given the endemic nature of Rule 13.1 dismissals in 2021, many counsel will encounter NOIDs even when taking these steps – particularly counsel who represent clients who were unrepresented at the pleadings stage. Thus, counsel should be prepared to draft NOID submissions and to identify cases for reconsideration and/or judicial review as required.

Although these recommendations are targeted towards Applicant counsel, Respondent counsel should also be concerned about the trends reported in this work – all parties to human rights litigation rely on a competent and fair Tribunal to justly resolve disputes. To the extent that the Tribunal might be dismissing cases that ought to proceed, Respondent counsel should be concerned about the strength of the Tribunal as an institution. Further, the procedural delays created by NOIDs should be concerning to Respondent counsel – the process of the Tribunal initiating a NOID, the Applicant filing submissions, and the Tribunal determining whether the Application will proceed can take many months. If the Tribunal permits an application to proceed after reviewing NOID submissions, this creates delay and potential prejudice to Respondents, who may not be made aware of allegations against them for a significant period of time after the Applicant has filed.

VI. Conclusion

In the first reading of Bill 107, the Hon. Michael Bryant said,

The Human Rights Code Amendment Act, 2006, if passed, would strengthen Ontario’s human rights [system]. Complaints of discrimination would be filed directly with an enhanced Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. It would improve access to justice for those who have faced discrimination and increase protection for the vulnerable […] Under the proposed system, all applicants would have that opportunity.65

Nearly a decade and a half later, this paper critically examines if the spirit of these objectives has been achieved. This research demonstrates brings to the fore questions of institutional competence, access to justice, and procedural fairness in Ontario’s direct access human rights system. It is quantitatively observable that the Tribunal is increasingly relying on Rule 13.1 dismissals to dispose of claims. In doing so, the Tribunal relies on an expansive definition of jurisdiction to dismiss cases without providing the Applicant an oral hearing. The qualitative aspect of this work probes deeper into which cases may be at an elevated risk of dismissal under Rule 13.1, suggesting that many applicants are receiving NOIDs in cases where their pleadings do disclose a prima facie breach of the Code. This is particularly observed in instances where self-represented Applicants struggled to turn their experiences into a compelling or succinct legal narrative. In a system premised on direct access to adjudication, the trends reported herein should concern every Ontarian that is committed to building a province free from the forms of discrimination protected under the Code.

Bibliography

Legislation

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act , RSO 1990, c F.31.

Human Rights Code, RSO 1990, c. H.19.

Human Rights Code Amendment Act, 2006, SO, 2006, C. 30-Bill 107.

Statutory Powers Procedure Act, RSO 1990, c. S.22.

Jurisprudence

Atkinson v. Parliamentary Protective Service, 2021 HRTO 562.

Boissinot v. Aiana Restaurant, 2021 HRTO 280.

Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65.

Civiero v. Habitat for Humanity Restore, 2021 HRTO 257.

CL as represented by Litigation Guardian KL, 2021 HRTO 159.

Dabic v Windsor Police Service, 2010 HRTO 1994.

Forde v. Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2011 HRTO 1389.

Gal v. Jaytex Group of Canada Ltd., 2013 HRTO 867

Goswami v. Ontario Power Generation, 2021 HRTO 1066

Groblicki v. Watts Water, 2021 HRTO 461

Hunt v Carey Canada Inc., [1990] 2 SCR 959.

Khan v. Ottawa (University of), 1997 CanLii 941

R.B. v. Keewatin-Patricia District School Board, 2013 HRTO 1436

Masood v. Bruce Power, 2008 HRTO 381

Moore v. British Columbia (Education), 2012 SCC 61

Sharma v. Toronto (City), 2020 HRTO 949.

Worley v. Ontario Cycling Association, 2016 HRTO 1246

Secondary sources

Anand, Raj, Kathy Laird & Ron Ellis, “Opinion: Justice delayed: The decline of the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal under the Ford government”, Globe and Mail (29 January 2021), online.

Daly, Paul, “The Principle of Stare Decisis in Canadian Administrative Law” (November 2, 2015) (2016) 49(1) Revue juridique Thémis 757.

Cornish, Mary, Rick Miles & Ratna Omidvar, Achieving Equality: A Report on Human Rights Reform, Ontario Human Rights Code Review Task Force (26 June 1992).

Flaherty, Michelle, “Ontario and the Direct Access Model to Human Rights” in Ken Norman, Lucie Lamarche & Shelagh Day, eds, 14 Argum Favour Hum Rights Inst (Irwin Law, 2014).

Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, “Practice Direction on New Case Processing System and Case Management Conference Calls”, (1 March 2018) Online: Tribunals Ontario

Ontario, Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Hansard, 38th Parl, 2nd Sess, No 66A (26 April 2006).

Pinto, Andrew, “Report of the Ontario Human Rights Review 2012”, Submitted to the Honourable John Gerretsen Attorney General of Ontario, online (pdf): Publications Ontario.

Rules of Procedure for Applications under the Human Rights Code, Part IV, R.S.O. 1990, c.H.19 as amended, online

Sandill, Richa & Emily Shepard, “The New Gatekeeper – A Review of Recent Early Dismissal Hearings at HRTO”, Annual Update on Human Rights (2021), Online (pdf)

Tribunals Ontario, “2020-21 Annual Report”, Online: Tribunals Ontario.

Tribunals Ontario, “2010-2011 Annual Report”, Online: Tribunals Ontario.

Tribunals Ontario, “2012-2013 Annual Report”, Online: Tribunals Ontario.

Tribunals Ontario, “2013-2014 Annual Report”, Online: Tribunals Ontario

Appendix A: NOID Types and their standard templates

Group A: Clear jurisdictional issues

Standard limitation period issue (LP(S))

- the Application was filed more than one year after the last incident of discrimination described in your Application and you do not appear to have cited facts that constitute “good faith” within the meaning of the HRTO’s case law [s.34(1)]. See for example Thomas v. Toronto Transit Commission, 2009 HRTO 1582 (CanLII) and see for example Diler v. Cambridge Memorial Hospital, 2010 HRTO 1224 (CanLII) for a discussion of “good faith”.

Constitutional Jurisdiction (CJ)

- the respondent appears to be a federal government department, agency or a federally regulated employer or service provider. See for example Masood v. Bruce Power, 2008 HRTO 381 (CanLII).

s 45.1 (45)

- rejeter la Requête parce les motifs de celle-ci ont déjà été traités de façon appropriée dans le cadre d’une autre instance – voir l’art. 45.1 du Code des droits de la personne (le « Code »).

(rough translation): Dismiss the application because the allegations are already appropriately dealt with through another forum, per s 45.1 of the Human Rights Code

46= Civil proceeding initiated/ongoing

- a civil proceeding has been commenced in a court in which you are seeking an order under section 46.1 with respect to the alleged Code infringement and the proceeding has not been finally determined or withdrawn, or the court has finally determined the issue of whether the right has been infringed, or the matter has been settled [s. 34(11)]. See for example Beaver v. Dr. Hans Epp Dentistry Professional Corporation, 2008 HRTO 282 (CanLII).

Adjudicative Immunity (AI)

- the respondent is an arbitrator, adjudicator or judge. The HRTO has stated that it has no jurisdiction to hear applications against courts and tribunals based on the execution of adjudicative duties or decision-making because of the doctrine of judicial or adjudicative immunity: see Cartier v. Nairn 2009 HRTO 2208 (CanLII); Hazel v. Ainsworth Engineered Corp. 2009 HRTO 2180 (CanLII); Seberras v. Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, 2012 HRTO 115 (CanLII).

Provincial jurisdiction (PJ)

- the events described in your Application do not appear to be connected to Ontario. See for example Cash v. Stryker, 2009 HRTO 1738 (CanLII).

Counsel Conduct (CC)

- the issues raised relate to the conduct of a lawyer representing a party in another legal proceeding. The HRTO has stated that the relationship between a lawyer and an opposing party is not covered by the Code: Belso v. York Region Police, 2009 HRTO 757 (CanLII); Cooper v. Pinkofskys, 2008 HRTO 390 (CanLII).

Group B: Issues warranting further analysis

Forde (FD)

- a review of the Application and the narrative setting out the incidents of alleged discrimination fails to identify any specific acts of discrimination within the meaning of the Code allegedly committed by the respondent(s). The Tribunal does not have jurisdiction over general allegations of unfairness unless the unfairness is connected, in whole or in part, to one of the grounds specifically set out in Part I of the Code (e.g. race, disability, sex, etc.); see, for example, Forde v. Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2011 HRTO 1389).

Bald Assertion (BA)

- The Application identifies enumerated Code grounds and asserts that the applicant received adverse treatment at the hands of the respondent but does not clearly explain why the applicant believes the adverse treatment was because of the enumerated grounds. The Tribunal does not have jurisdiction over general allegations of unfairness. To come within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, the narrative setting out the incident(s) of discrimination must provide some factual basis which links the respondent’s conduct to the applicant’s Code enumerated ground(s). A bald assertion that the adverse treatment the applicant received was owing to their enumerated ground is not enough to provide the required factual basis. See, for example, Groblicki v. Watts Water, 2021 HRTO 461 and Forde v. Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2011 HRTO 1389).

No Social area (SA)

- The Application does not appear to allege discrimination with respect to any of the social areas identified in the Code (services, goods, and facilities; accommodation (housing); contracts; employment; membership in vocational associations). See Noor v. Midyanta Community Services, 2012 HRTO 375 (CanLII), MF V. Child and Family Services of TImmis and District 2009 HRTO 979 (CanLII)

No coherent narrative (CN)

- the Application fails to set out a coherent narrative that explains the particulars of the alleged discrimination and discloses a basis on which the applicant’s allegations are connected to the Code and to the respondents. To be able to make a determination that the Application is within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, the HRTO requires a concise statement from the applicant that clearly describes each incident of alleged discrimination in chronological order, including the date, place, and people involved. This statement must be no more than five (5) pages long

No Reprisal (NR)

- you allege discrimination based on “reprisal or threat of reprisal” but have failed to explain how the respondent’s behaviour was related to any of the following: claiming or enforcing a right under the Code; instituting or participating in proceedings under the Code; or, refusing to infringe the right of another person under the Code [s. 8]. See for example Mirea v. Canadian National Exhibition, 2009 HRTO 32 (CanLII); Chan v. Tai Pan Vacations, 2009 HRTO 273 (CanLII).

Limitation period (can’t identify act of discrimination identified in question 7) (LP(7))

- while your response to question #7 of the Application alleges that the last incident of discrimination you experienced occurred on _____, it is either not clear what incident of discrimination is alleged to have occurred on this date or how the incident described as occurring on that date constitutes an incident of discrimination within the meaning of the Code. See for example Miller v. Prudential Lifestyles Real Estate, 2009 HRTO 1241 (CanLII); Mafinezam v. University of Toronto, 2010 HRTO 1495 (CanLII); and Garrie v. Janus Joan Inc., 2012 HRTO 1955. The HRTO does not have the power to consider claims filed more than one year after the last incident of discrimination or the last in a series of incidents of discrimination unless the delay in filing was incurred in good faith and no substantial prejudice will result to any person affected by the delay [s.34(1)]. You do not appear to have cited facts that constitute “good faith” within the meaning of the HRTO’s case law. See for example Thomas v. Toronto Transit Commission, 2009 HRTO 1582 (CanLII) and see for example Diler v. Cambridge Memorial Hospital, 2010 HRTO 1224 (CanLII) for a discussion of “good faith”.

COVID-19 Mask case, meds required (C-19)

- In your Application, you state that you are medically exempt from wearing a mask. For your Application to continue to be processed, you must provide medical evidence that not only identifies your disability or disabilities within the meaning of the Code but also explains how the disability or disabilities prevent you from wearing a mask. See Civiero v. Habitat for Humanity Restore, 2021 HRTO 257 and Sharma v. Toronto (City), 2020 HRTO 949 and CL as represented by Litigation Guardian KL, 2021 HRTO 159.

Endnotes

1 Ontario, Legislative Assembly of Ontario,

Hansard, 38

th Parl, 2

nd Sess, No 66A (26 April 2006) at 3289 (Hon Michael Bryant, AG) [“Hansard Record”].

2 Human Rights Code, RSO 1990, c. H.19 [“

Code”].

5 The Form 1 is the document that forms the basis for all pleadings in front of the Tribunal.

6 2011 HRTO 1389 [

Forde].

7 A

prima facie breach of the

Code is made out when three elements are in place. The applicant must demonstrate: 1) that they have a characteristic protected from discrimination (e.g., a ground of discrimination is present), 2) they have experienced an adverse impact within a social area protected by the

Code, and 3) the protected characteristic was a factor in the adverse impact (see e.g.,

Moore v. British Columbia (Education), 2012 SCC 61;

R.B. v. Keewatin-Patricia District School Board, 2013 HRTO 1436 at para. 204.)

8 Michelle Flaherty, “Ontario and the Direct Access Model to Human Rights” in Ken Norman, Lucie Lamarche & Shelagh Day, eds,

14 Argum Favour Hum Rights Inst (Irwin Law, 2014) at 171.

9 SO, 2006, C. 30-Bill 107.

10 Hansard Record,

supra note 1 at 3289.

11 Mary Cornish, Rick Miles & Ratna Omidvar, “Achieving Equality: A Report on Human Rights Reform”, Ontario Human Rights Code Review Task Force (26 June 1992).

13 Code,

supra note 2 at ss 13 and 45.12.

15 Flaherty,

supra note 3 at 190.

21 See Tribunals Ontario Annual Reports,

supra notes 4, 17, 19, 20.

22 Together these three authors bring significant expertise in human rights and administrative law. Per the cited article, Raj Anand is a partner an WierFoulds LLP, and has previously been appointed to positions at the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the HRLSC Board of Directors, and as an adjudicator at the Tribunal. Kathy Laird has likewise served as an adjudicator at the Tribunal, counsel to the Tribunal, and as a director at the HRLSC. Ron Ellis holds a PhD in administrative law and has served as the first chair of the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Tribunal.

24 2020-2021 Annual Report,

supra note 3.

26 Statutory Powers Procedure Act, RSO 1990, c. S.22 at s 25.1.

27 Code,

supra note at s 43(1).

30 See e.g.,

Masood v. Bruce Power, 2008 HRTO 381.

31 Masood, ibid at para 6.

33 See e.g.,

Masood, ibid at para 6

; Worley v. Ontario Cycling Association, 2016 HRTO 1246 [

“Worley”];

Goswami v. Ontario Power Generation, 2021 HRTO 1066 at para 5,

Atkinson v. Parliamentary Protective Service, 2021 HRTO 562 at para 4.

34 [1990] 2 SCR 959 at 980.

35 Rules of Procedure,

supra note 26 at r 19.1A.

36 2010 HRTO 1994 [

Dabic].

38 Dabic,

supra note 35 at paras 8-9.

40 Filed pursuant to

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, RSO 1990, c F 31.

41 NOID interviews are booked by HRLSC intake staff anytime a caller contacts the Centre after receiving a NOID. A NOID interview consists of summary legal advice, given by HRLSC counsel. If the client meets internal criteria for further services HRLSC may be retained to draft NOID submissions after the initial interview.

43 A

prima facie breach of the

Code is made out when three elements are in place. The applicant must demonstrate: 1) that they have a characteristic protected from discrimination (e.g., a ground of discrimination is present), 2) they have experienced an adverse impact within a social area protected by the

Code, and 3) the protected characteristic was a factor in the adverse impact (see e.g.,

Moore v. British Columbia (Education), 2012 SCC 61;

R.B. v. Keewatin-Patricia District School Board, 2013 HRTO 1436 at para. 204.)